Having failed so miserably to identify the seventeen errors in What Is Wrong In This Room?, I need to try again, if only for my self-esteem. So here goes, another puzzle from my 1927 copy of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia: What Is Wrong With This Steamer?

I am going to cruise through this because I know all about ships. I’ve

got nautical blood. My great-grandpa was a master mariner and my dad

used to take me to watch tide-time at Goole docks. We had books about ships, used to play with toy ships and went to see the Queen Mary sail. I’ve been on the cross channel ferry, sailed a model yacht across the West Park pond and circumnavigated Peasholm Park lake in a swan pedalo. My wife’s grandfather wrote books about sailing. It’s going to be a sea-breeze. I’m on course for a fleet of

ten out of ten. So, full steam ahead Captain, all hands on deck, let’s cast off and get under way.

Just look at those Roman numerals on the bow. They are supposed to show how deep the ship is floating in the water so should obviously run from bottom to top. And while we’re looking at the bow, where is the ship’s name? As for those rope ladders up the mast, they have no rungs at the top. Easy! We’ve logged 3/3, a fair rate of knots.

Is this the calm before the storm? Sailing close to the wind, I sneak a look at the answers. I must have had only one oar in the water not to realise that portholes open inwards, not outwards, as should that square shaped hatch. Evidently it’s a scupper for draining water from the deck. That scuppered me. But is the marking scheme above board to tally these as two answers? If so, it’s only 3/5 now.

We’re into deep water. We’ll batten down the hatch and press on, but I can’t fathom out any more. The answers say that the foremast and funnels should lean backwards rather than forwards. Oh come on! You can hardly tell. It might help if the drawing was shipshape. And does it fit the bill to score these as yet another two. I’m all at sea with 3/7.

The next ones leave us becalmed in the doldrums. The waste steam pipes should be in front of the funnels rather than at the sides – I didn’t even realise what they were – and you would really need to know the ropes to realise that ships do not lower their anchors in dock. The answers then say that the anchor-chain hole is the wrong way: presumably it should be more vertical than horizontal. All right, I didn’t spot these, but ahoy Arthur Mee, matey, don’t you know that an “anchor-chain hole” is correctly called a hawsehole? I’ll hazard that every nineteen-twenties child would have known that. I should get extra credit, even if I only remembered it because it sounds rude. I’m sunk with 3/10.

But what’s this – an eleventh answer, or is it thirteen? It said there were only ten. There are no ventilators (those sticking up tuba shaped things you see on ships). Nor are there any halyards or foretop-mast stays. No what? I’ve had to google those. It’s beginning to sound like a verse from What Shall We Do With A Drunken Sailor.

Well, I’m pooped. Shiver my timbers. That’s taken the wind out of my sails. But if Arthur Mee is going to take us aback with supernumerary answers, then I should get my extra hawsehole mark, so 4/11, or 36%. In my university days that would have been a refer grade. I demand another re-sit, to start again with a clean slate. I’m up in the crow’s nest on look out for another puzzle.

Google Analytics

Tuesday, 26 December 2017

Sunday, 17 December 2017

Review - Laurie Lee: Red Sky at Sunrise

Red Sky at Sunrise (1992) is a trilogy of Laurie Lee's memoirs: Cider With Rosie (1959), As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning (1969) and A Moment of War (1991). (5*)

Lee is a master of metaphor and simile. They come so thick and fast on every page, so astonishing in their aptness and originality, it is impossible to pick any one example above another, but here are some from google search. One could never begin to emulate him.

Cider With Rosie is a recollection of his Cotswold childhood in Slad, near Stroud, Gloucestershire during the nineteen-teens and -twenties. As I Walked Out ... tells of leaving home to work in London, and then travelling around Spain in the nineteen thirties. A Moment of War is an account of his experiences on returning to Spain to fight in the Civil War, a period he was lucky to survive. Cider With Rosie is the most lyrical and impressionistic of the three. The others pull you along with a much stronger narrative.

Key to star ratings: 5*** wonderful and hope to read again, 5* wonderful, 4* enjoyed it a lot and would recommend, 3* enjoyable/interesting, 2* didn't enjoy, 1* gave up.

Previous book reviews

Lee is a master of metaphor and simile. They come so thick and fast on every page, so astonishing in their aptness and originality, it is impossible to pick any one example above another, but here are some from google search. One could never begin to emulate him.

Cider With Rosie is a recollection of his Cotswold childhood in Slad, near Stroud, Gloucestershire during the nineteen-teens and -twenties. As I Walked Out ... tells of leaving home to work in London, and then travelling around Spain in the nineteen thirties. A Moment of War is an account of his experiences on returning to Spain to fight in the Civil War, a period he was lucky to survive. Cider With Rosie is the most lyrical and impressionistic of the three. The others pull you along with a much stronger narrative.

Key to star ratings: 5*** wonderful and hope to read again, 5* wonderful, 4* enjoyed it a lot and would recommend, 3* enjoyable/interesting, 2* didn't enjoy, 1* gave up.

Previous book reviews

Sunday, 10 December 2017

Hayley Payley Snow On The Ground

My dad used to sing a strange Christmas song that hardly anyone seems to know now. It went like this:

“What’s all that about?” I wanted to know in later years. “What does ‘haley paley’ mean?”

“No idea” he said, “but Franky Drury used to sing another verse, a rude one.”

He would never tell me what it was.

Some years ago I looked for the song on the internet and found nothing. Looking again now, there is still very little. The story it tells seems to have been related to an old English and American ballad called The Soldier’s Poor Little Boy or The Poor Little Sailor Boy. Recordings include a 1927 version by the Johnson Brothers, one from the Max Hunter Folk Collection sung by Reba Dearmore in 1969 and a 1922 recording by C. K. Tillett. In at least one version, the lady takes the boy in because her own son has been killed in battle. In others the boy turns out to be the lady’s long lost son “William that’s come from the sea”. There were more verses with several variations, but my dad only sang the words above.

There are also possible references to the Poor Little Sailor Boy title in nineteenth century newspapers. The earliest I found was in the Norfolk Chronicle or Norwich Gazette of 25th July, 1807. If that does not seem particularly old, we should bear in mind that many of what we think of as ancient Christmas carols were written as recently as the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The tune for Haley Paley, however, is quite different to The Poor Soldier/Sailor Boy. The Yorkshire Garland Group (an archive of Yorkshire folk song heritage) has a seven-verse version in 6/8 time, which appeared on a 1971 LP Transpennine, performed briskly by Harry Boardman and Dave Hillery (unfortunately, the YouTube links to the individual tracks are now blocked). The site also refers to a shorter variation called Early Pearly sung in slower 3/4 waltz time by an eighty-five year old from Hull in 2009. At the end she moves into a second tune similar to the American recordings above. If “hayley payley snow” is a corruption of “early pearly snow”, that at least makes sense. There is also a discussion at The Mudcat Café which suggests the song was sung mainly in Yorkshire. I wonder how many of these orally-transmitted songs are now lost forever.

My dad’s tune (below) differed only slightly from the Hull one. As the Garland Group web site observes, such variation is the nature of oral transmission.

Haley paley snow on the groundWhen he got to “come in, come in”, he pretended to pull me towards him, malevolently, like a monster or one of those evil deviants we never used to mention.

The wind was bitter and cold

When a poor little sailor boy covered in rags

Came to a lady’s door.

The lady looked out of her window on high

And cast her eye upon him

Come in, come in you poor little child

You never shall want any more.

“What’s all that about?” I wanted to know in later years. “What does ‘haley paley’ mean?”

“No idea” he said, “but Franky Drury used to sing another verse, a rude one.”

He would never tell me what it was.

Some years ago I looked for the song on the internet and found nothing. Looking again now, there is still very little. The story it tells seems to have been related to an old English and American ballad called The Soldier’s Poor Little Boy or The Poor Little Sailor Boy. Recordings include a 1927 version by the Johnson Brothers, one from the Max Hunter Folk Collection sung by Reba Dearmore in 1969 and a 1922 recording by C. K. Tillett. In at least one version, the lady takes the boy in because her own son has been killed in battle. In others the boy turns out to be the lady’s long lost son “William that’s come from the sea”. There were more verses with several variations, but my dad only sang the words above.

There are also possible references to the Poor Little Sailor Boy title in nineteenth century newspapers. The earliest I found was in the Norfolk Chronicle or Norwich Gazette of 25th July, 1807. If that does not seem particularly old, we should bear in mind that many of what we think of as ancient Christmas carols were written as recently as the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The tune for Haley Paley, however, is quite different to The Poor Soldier/Sailor Boy. The Yorkshire Garland Group (an archive of Yorkshire folk song heritage) has a seven-verse version in 6/8 time, which appeared on a 1971 LP Transpennine, performed briskly by Harry Boardman and Dave Hillery (unfortunately, the YouTube links to the individual tracks are now blocked). The site also refers to a shorter variation called Early Pearly sung in slower 3/4 waltz time by an eighty-five year old from Hull in 2009. At the end she moves into a second tune similar to the American recordings above. If “hayley payley snow” is a corruption of “early pearly snow”, that at least makes sense. There is also a discussion at The Mudcat Café which suggests the song was sung mainly in Yorkshire. I wonder how many of these orally-transmitted songs are now lost forever.

My dad’s tune (below) differed only slightly from the Hull one. As the Garland Group web site observes, such variation is the nature of oral transmission.

Wednesday, 1 November 2017

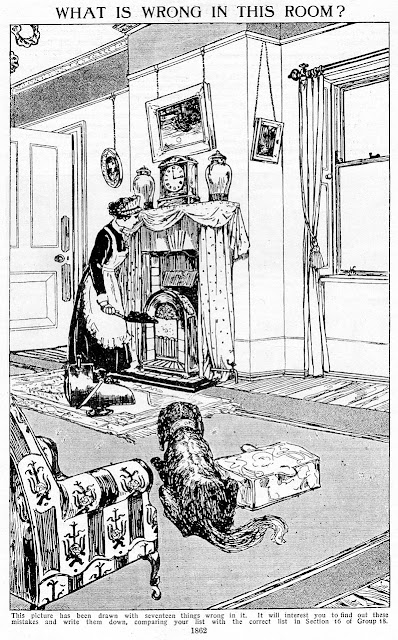

What Is Wrong In This Room?

Brian’s Blog recently reminded me of the puzzles in Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia.

Browsing Volume 3 a month or two ago, I came across the puzzle “What Is Wrong In This Room?” which invites you to find seventeen things wrong in a drawing of, presumably, a typical early twentieth-century sitting room. It struck me how different it is from today’s homes, so different that finding all seventeen is nigh impossible.

I got off to a good start: it slowly dawned on me that the door knob should not be on the hinge side of the door and that the picture above the fireplace is upside down. I didn’t spot the problems with the other two pictures though: that the one near the window is not hooked on to the picture rail, and that the hook for the picture near the door is upside down. How many rooms still have picture rails these days anyway? And what about the large skirting board? Who would spot that it is upside down in the drawing? It looks fine to me. (Score so far: 2/5).

Oh dear, but now for two I might have got with the shrewd intelligence of Miss Marple and the observational acuteness of Sherlock Holmes: qualities I clearly do not possess. The floorboards at the two sides of the carpet run in different directions (no fitted carpets then), and the hands on the clock are not in the correct positions because if the big hand is showing quarter-past, then the little hand should be past the hour rather than before. I got neither of these. It is starting to be as demeaning as University Challenge. (Score now 2/7).

It gets harder. Do any of us still have maids (unless you count wives), or coal fires for that matter? It appears that the hinged handle of the coal-scuttle is unusable – some people will never have heard of coal scuttles – and that the fire the maid is about to load with coal is a gas fire (you just can’t get the staff!). When you look carefully you can see that it is not fully inside the fireplace, and there is also a supply pipe. We used to have a portable stand-alone gas fire similar to that which connected to a gas tap by a long rubber tube. That was in the nineteen-fifties. Where did the fumes go? Poison! Perhaps that’s why my score now sinks to 2/9.

I put my failure to identify the next ones down to the poor resolution of the drawing – a convenient excuse, I know, but did you notice that the curtain-pole support is fastened on top rather than at the side, making it impossible to put the pole over it, or that the window shutter knob is (like the door) on the wrong side? I didn’t but I’m getting irritated now because is it not possible to slide the pole through, and don’t the window shutters look like folding double-hinged ones which open out to the middle, in which case the knob would be on the right side? Who has window shutters anyway? The answers also say that the window fastener is the wrong way round (the flatter part you move with your thumb is against the window), and that the handle by which we lift the lower half is fixed back to front. I suppose when it comes down to it they are, but you’d think they would be drawn so as to give you at least half a chance of being able to see. Maybe those still with sash windows did better here. An unjust 2/13.

Did you do any better with the soft-furnishings? The box-shaped thing next to the dog is evidently a hassock – a what – a hassock, like the cushions you kneel on in church (well that’s if you go). You are doing very well if you realised that the handle-lugs should be at the ends rather than at the sides. And then there is the chair. The answers say the pattern is upside down. When you rotate the image you can see it appears to show a bird on some kind of perch, but really? And then there is the chair castor which is supposed to be fixed the wrong way round so that it would break under weight. I don’t understand that one at all. When were swivelling ones invented? (2/16).

Lastly, the dog. I’m not a doggy person, that’s my excuse, but I would be surprised if you got it even if you are. It is a spaniel with a collie’s tail. Couldn’t it be just a mongrel?

So, 2/17 for me, 12%, an unmitigated, dismal fail. Even with a lucky resit I doubt I would manage more than six or seven.

The ten volumes of this encyclopedia were bought in 1927. Were children a lot cleverer then, or is it just that the once-familiar has changed beyond recognition?

Perhaps we should set a modern version that they wouldn’t be able to do – a central heating radiator with the pipes attached to the top rather than the bottom, a light with a missing bulb and a television with an image on the screen despite not being plugged in. And how wrong they would be when they said that that our pictures had no support at all. That would show ‘em we‘re not stupid.

You might also like What Is Wrong With This Steamer? and Knockout, Knowledge and Arthur Mee.

Browsing Volume 3 a month or two ago, I came across the puzzle “What Is Wrong In This Room?” which invites you to find seventeen things wrong in a drawing of, presumably, a typical early twentieth-century sitting room. It struck me how different it is from today’s homes, so different that finding all seventeen is nigh impossible.

I got off to a good start: it slowly dawned on me that the door knob should not be on the hinge side of the door and that the picture above the fireplace is upside down. I didn’t spot the problems with the other two pictures though: that the one near the window is not hooked on to the picture rail, and that the hook for the picture near the door is upside down. How many rooms still have picture rails these days anyway? And what about the large skirting board? Who would spot that it is upside down in the drawing? It looks fine to me. (Score so far: 2/5).

Oh dear, but now for two I might have got with the shrewd intelligence of Miss Marple and the observational acuteness of Sherlock Holmes: qualities I clearly do not possess. The floorboards at the two sides of the carpet run in different directions (no fitted carpets then), and the hands on the clock are not in the correct positions because if the big hand is showing quarter-past, then the little hand should be past the hour rather than before. I got neither of these. It is starting to be as demeaning as University Challenge. (Score now 2/7).

It gets harder. Do any of us still have maids (unless you count wives), or coal fires for that matter? It appears that the hinged handle of the coal-scuttle is unusable – some people will never have heard of coal scuttles – and that the fire the maid is about to load with coal is a gas fire (you just can’t get the staff!). When you look carefully you can see that it is not fully inside the fireplace, and there is also a supply pipe. We used to have a portable stand-alone gas fire similar to that which connected to a gas tap by a long rubber tube. That was in the nineteen-fifties. Where did the fumes go? Poison! Perhaps that’s why my score now sinks to 2/9.

I put my failure to identify the next ones down to the poor resolution of the drawing – a convenient excuse, I know, but did you notice that the curtain-pole support is fastened on top rather than at the side, making it impossible to put the pole over it, or that the window shutter knob is (like the door) on the wrong side? I didn’t but I’m getting irritated now because is it not possible to slide the pole through, and don’t the window shutters look like folding double-hinged ones which open out to the middle, in which case the knob would be on the right side? Who has window shutters anyway? The answers also say that the window fastener is the wrong way round (the flatter part you move with your thumb is against the window), and that the handle by which we lift the lower half is fixed back to front. I suppose when it comes down to it they are, but you’d think they would be drawn so as to give you at least half a chance of being able to see. Maybe those still with sash windows did better here. An unjust 2/13.

Did you do any better with the soft-furnishings? The box-shaped thing next to the dog is evidently a hassock – a what – a hassock, like the cushions you kneel on in church (well that’s if you go). You are doing very well if you realised that the handle-lugs should be at the ends rather than at the sides. And then there is the chair. The answers say the pattern is upside down. When you rotate the image you can see it appears to show a bird on some kind of perch, but really? And then there is the chair castor which is supposed to be fixed the wrong way round so that it would break under weight. I don’t understand that one at all. When were swivelling ones invented? (2/16).

Lastly, the dog. I’m not a doggy person, that’s my excuse, but I would be surprised if you got it even if you are. It is a spaniel with a collie’s tail. Couldn’t it be just a mongrel?

So, 2/17 for me, 12%, an unmitigated, dismal fail. Even with a lucky resit I doubt I would manage more than six or seven.

The ten volumes of this encyclopedia were bought in 1927. Were children a lot cleverer then, or is it just that the once-familiar has changed beyond recognition?

Perhaps we should set a modern version that they wouldn’t be able to do – a central heating radiator with the pipes attached to the top rather than the bottom, a light with a missing bulb and a television with an image on the screen despite not being plugged in. And how wrong they would be when they said that that our pictures had no support at all. That would show ‘em we‘re not stupid.

You might also like What Is Wrong With This Steamer? and Knockout, Knowledge and Arthur Mee.

Friday, 27 October 2017

Review - R. D. Blackmore: Lorna Doone

R. D. Blackmore

Lorna Doone (4*)

On holiday in Exmoor this summer, we walked along the idyllic Oare valley where Lorna Doone is set, and looked inside the ancient atmospheric church. It's a book I had heard of many times, but never read, so I downloaded the Kindle edition for free. It tells a long, complicated, many charactered story at the time of the English religious troubles of the sixteen-seventies and sixteen-eighties (although it was written almost two centuries later, published in 1869). Despite occasional difficulties with archaic language and the Exmoor dialect, and some irritation with the portrayal of most of the women as passive, ineffectual or just plain stupid, the action pulls you along through passages that evoke the rich Exmoor landscape, weather, plants and animals. Take time out to immerse yourself in seventeenth century rural Devon in this long and absorbing read.

Key to star ratings: 5*** wonderful and hope to read again, 5* wonderful, 4* enjoyed it a lot and would recommend, 3* enjoyable/interesting, 2* didn't enjoy, 1* gave up.

Lorna Doone (4*)

On holiday in Exmoor this summer, we walked along the idyllic Oare valley where Lorna Doone is set, and looked inside the ancient atmospheric church. It's a book I had heard of many times, but never read, so I downloaded the Kindle edition for free. It tells a long, complicated, many charactered story at the time of the English religious troubles of the sixteen-seventies and sixteen-eighties (although it was written almost two centuries later, published in 1869). Despite occasional difficulties with archaic language and the Exmoor dialect, and some irritation with the portrayal of most of the women as passive, ineffectual or just plain stupid, the action pulls you along through passages that evoke the rich Exmoor landscape, weather, plants and animals. Take time out to immerse yourself in seventeenth century rural Devon in this long and absorbing read.

Key to star ratings: 5*** wonderful and hope to read again, 5* wonderful, 4* enjoyed it a lot and would recommend, 3* enjoyable/interesting, 2* didn't enjoy, 1* gave up.

Saturday, 30 September 2017

Reviews: Ray Gosling: Sum Total and Personal Copy

Ray Gosling

Sum Total (3* to 5*)

Personal Copy: a Memoir of the Sixties (3* to 5*)

Ray Gosling was a writer and broadcaster who made television and radio programmes about ordinary people. His autobiographies, ‘Sum Total’ written when he was 21, and ‘Personal Copy’ when he was 40, are of varied consistency (some parts of them are 5*), but at their best are fascinating memoirs of the fifties and sixties. They document how, despite going to grammar school and university, which he left fairly quickly, he rejected any idea of a middle-class professional career and organized and campaigned for working-class causes. He conveys a strong sense of how the times they were a-changin’. His evocative eulogy to the now lost St. Ann's community of Nottingham is extraordinary.

My next post is about his film about Goole.

Key to star ratings: 5*** wonderful and hope to read again, 5* wonderful, 4* enjoyed it a lot and would recommend, 3* enjoyable/interesting, 2* didn't enjoy, 1* gave up.

Previous book reviews

Sum Total (3* to 5*)

Personal Copy: a Memoir of the Sixties (3* to 5*)

Ray Gosling was a writer and broadcaster who made television and radio programmes about ordinary people. His autobiographies, ‘Sum Total’ written when he was 21, and ‘Personal Copy’ when he was 40, are of varied consistency (some parts of them are 5*), but at their best are fascinating memoirs of the fifties and sixties. They document how, despite going to grammar school and university, which he left fairly quickly, he rejected any idea of a middle-class professional career and organized and campaigned for working-class causes. He conveys a strong sense of how the times they were a-changin’. His evocative eulogy to the now lost St. Ann's community of Nottingham is extraordinary.

My next post is about his film about Goole.

Key to star ratings: 5*** wonderful and hope to read again, 5* wonderful, 4* enjoyed it a lot and would recommend, 3* enjoyable/interesting, 2* didn't enjoy, 1* gave up.

Previous book reviews

Thursday, 28 September 2017

People who can‘t say ‘ull

The BBC Radio Four announcer said this afternoon that in half an hour there would be a programme about the 2017 City of Culture.

“I know where he means” I thought, but then he mystified me by saying it was about the Ezzall area of the city. It took me a moment to realise he meant ‘essle. There is a difference. In trying to mimic the local accent, he had over-emphasised the initial E.

Like the friend I had when I worked in Scotland. No matter how hard she tried, no matter how many times I demonstrated, she could never say ‘ull without it sounding wrong. The initial U was too strong, almost beginning with a glottal stop. The voice-onset came too soon. It’s a soft gentle U after the dropped H, not a hard one.

It seems to my ears that people not from the region cannot say ‘ull or ‘essle properly, or for that matter ‘owden, ‘edon, ‘altemprice or ‘umber. Please, unless you grew up in East Yorkshire or thereabouts, don’t try. Just put the H in.

The programme, incidentally, was Hull 2017: The Spirit of Hessle Road.

“I know where he means” I thought, but then he mystified me by saying it was about the Ezzall area of the city. It took me a moment to realise he meant ‘essle. There is a difference. In trying to mimic the local accent, he had over-emphasised the initial E.

Like the friend I had when I worked in Scotland. No matter how hard she tried, no matter how many times I demonstrated, she could never say ‘ull without it sounding wrong. The initial U was too strong, almost beginning with a glottal stop. The voice-onset came too soon. It’s a soft gentle U after the dropped H, not a hard one.

It seems to my ears that people not from the region cannot say ‘ull or ‘essle properly, or for that matter ‘owden, ‘edon, ‘altemprice or ‘umber. Please, unless you grew up in East Yorkshire or thereabouts, don’t try. Just put the H in.

The programme, incidentally, was Hull 2017: The Spirit of Hessle Road.

Labels:

2000-2020s,

accents and language,

Hull,

humour,

Rawcliffe/Goole/Howden

Wednesday, 20 September 2017

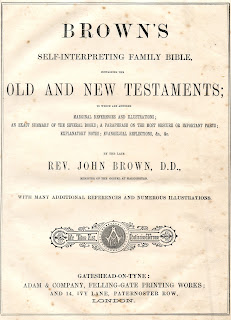

Brown’s Self-Interpreting Family Bible

Is it a sin to destroy a bible? I fear I may have committed sacrilege, not just once but three times over: to God, to my ancestors and to lovers of old books everywhere.

A few years ago I inherited a small suitcase containing a copy of Brown’s enormous Self-Interpreting Family Bible, which my father in turn had inherited from his Grandad Dunham. “You’d better take this” he was told, so he rode home with it balanced on his bicycle handlebars.

It was in pitiful condition: torn and loose pages, detached spine and end boards, faded gilt titles and tarnished metal stubs where clasps once fastened. It was stuck up with yellow tape where someone had tried to repair it. It smelt old and fusty. It deposited dusty specs of decaying leather and paper wherever you put it down. It seemed to be infested with mites. A metaphor, perhaps, for Christianity in the twenty-first century of the Common Era.

It was as big as a breeze block: about 13 x 10 x 3¼ inches (33½ x 25½ x 8½ centimetres) with over 1,100 pages. Once it would have been very beautiful book. Grandad Dunham, a devout Methodist, would have kept it constantly on display on a special table in the best room of the house, open at the page he was currently studying.

However, it was not really his. It was his wife’s. The inscription inside reads:

Miss E MannIt must have cost a lot of money, a sacrifice, but she herself was unable to read it. When she married Grandad Dunham she could only sign the Register with ‘X’ her mark. It seems unlikely that her parents could read it either. Perhaps they gazed in awe at the beautiful pictures inside, learnt their stories and meanings, and got someone else to write the inscription.

A present from

Her Dearly Beloved Mother

On Her twenty first

Birthday March 30th

1887

Amber Hill

Sutterton Fen

The full title was:

Browns Self-Interpreting Family Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments, to which are annexed marginal references and illustrations, an exact summary of the several books, a paraphrase of the most obscure or important parts, explanatory notes, evangelical reflections, &., &., by the late Rev. John Brown, Minister of the Gospel at Haddington, with many additional references and numerous illustrations.Nothing like a snappy title is there, but how was it self-interpreting? It seems to be down to the copious explanations and cross-references throughout, so thorough they effectively paraphrase the whole thing. For example, on the following page from Genesis, the notes are longer than the actual text:

God, with most exquisite art and skill, formed man’s body of the dust ... and so made him [human] the Reverend Brown interprets Verse 7 for us, and then cross-references this to similar assertions such as: we are the clay, and thou our potter. He continues in similar vein throughout the whole of the Old and New Testaments, exactly what you might expect from a man who despite minimal formal education taught himself Greek, Latin and Hebrew. His fellow members of the Secession Church in Scotland felt so inadequate they thought his learning must have come straight from the devil. He was like a living computer with the NVivo software.

Yet there is more. As well as the Old and New Testaments, there is a section on the life of the author (1772-1787), followed by a multi-chapter introduction which includes the geography and history of the biblical nations. He really had it in for Moslems:

About A.D. 608, Mahomet, a crafty Ishmaelite, assisted, it is said, by a villainous Jew and a treacherous Christian monk ... contrived a religious system ... promising to those who embraced it manifold carnal enjoyments, both in time and in eternity.Mahomet’s followers are likened to locusts and scorpions, with men’s beards, but hair plaited like women’s, who ravaged and murdered the nations. They pretended to a masculine religion but their character was marked by lust for women, revenge and cruelty.

If you think that’s not very complimentary, look at what he says about the Romans. When they weren’t burning multitudes of Christians in heaps for Nero’s nocturnal recreation, they were having them torn to pieces by lions and tigers, or pulling off their flesh with pincers, or mangling them with broken pots, or roasting them between gentle fires, or pouring melted lead through holes into their bowels.

Who needs Game of Thrones? Bring on the heathens and their manifold carnal enjoyments. The Reverend Brown’s fire and brimstone sermons must have left his congregation shocked and awed to the core, wishing they could go out and buy the box set so as not to have to wait a whole week for the next instalment.

But, sadly, the bible is beyond repair and too big and dirty to keep. It has come to the end of its time. I have tried to palm it off to various relatives but none will even entertain the idea of having it. In good condition it might be worth £150 or more, but not this one. So, I have cut out and kept the inscription page, along with the pages between the Old and New Testaments where the details of family marriages, births and deaths have been recorded in various hands between 1889 and the nineteen-fifties. The rest is now in the paper recycling bin – not so different from what my dad imagined as he got older: a skip outside his house piled high with all his most treasured possessions: his books, his stamp album, his Panora school photograph with its frame and glass all smashed up, and the family bible on top.

Sinful? Yes I suppose it is. My only prayer now is that in the afterlife I won’t have to face the punishment of having melted lead poured into my bowels.

Labels:

dad,

genealogy,

reading and poetry,

religion

Sunday, 17 September 2017

Hornby ‘O’ Gauge Revisited

A couple of years ago I posted a visual reconstruction of my nineteen-fifties Hornby ‘O’ gauge clockwork train set.

I recently came across the following leaflets that came with the set, saved by my dad between the pages of an old family bible (click to enlarge, or save image for full-size):

Did you know that the handle on the winding key was designed to test the correct spacing between the rails?

It seems from the following that only boys who join are entitled to the privilege of free expert advice. Does that mean that girls had to pay? I’m tempted to send off one shilling and 3 pence (6p today) for the official badge and special booklet on my daughter’s behalf:

I recently came across the following leaflets that came with the set, saved by my dad between the pages of an old family bible (click to enlarge, or save image for full-size):

Did you know that the handle on the winding key was designed to test the correct spacing between the rails?

It seems from the following that only boys who join are entitled to the privilege of free expert advice. Does that mean that girls had to pay? I’m tempted to send off one shilling and 3 pence (6p today) for the official badge and special booklet on my daughter’s behalf:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)