I keep going on about how family history research can turn up fascinating and unexpected things. My wife’s great-great-grandmother, who was widowed at 19, re-married a high official of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, 40 years her senior (23 and 63). We therefore find well-connected, upper-class cousins amongst the distant relatives. Many were odd, or potty, or both. One of my favourites is this splendid gentleman, John Reginald Rowallane Armytage Moore. He was born in County Cavan in 1876.

Reginald lived in Ireland until his early twenties, and then moved to Vancouver as an estate agent. There, in 1909 aged 33, he met and married 22-year-old Amy (Maisie) Campbell-Johnston. Their story then becomes distinctly unusual.

On paper it seemed a perfect match. He was high-born Anglo-Irish, and she was descended from the first Marquess of Montrose. But Maisie left after just a few months. She told one relative it was because Reginald was gay, but I am not so sure. You will have to make up your own mind. Not that it would matter much these days, but it did then.

By 1911, Reginald is back in London alone, still an estate agent, while Maisie has gone to California to stay with a friend called George Mordecai. Soon afterwards, Reginald moved to Sydney, Australia, where a newspaper reports he had joined the rowing club, having previously won competitive rowing competitions in Canada.

He remained in the southern hemisphere up to and through the First World War, serving with different forces in different countries. He spent a period in the Matabeleland Mounted Police in Southern Rhodesia, and then served in the forces in both New Zealand and Australia. One would have expected someone of his background and class to have been an officer, but it appears he was only an ordinary serviceman. He seems to have found it easy to move around.

In New Zealand, he was one of the 23-strong relief force that sailed to Samoa in 1916 to replace part of the garrison there. New Zealand forces had been the first anywhere in the world to recapture land back from the Germans, i.e. Samoa, and the relief force was made up of men aged 40 and over to free up younger men to fight in Europe.

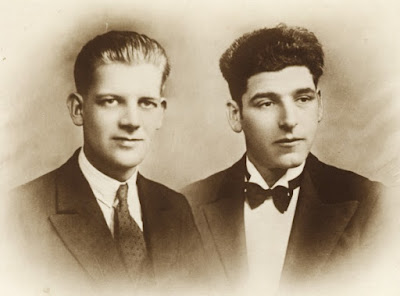

He turns up in Australia early in 1918. He enlisted as a gunner in the 12th Field Artillery Brigade, which sailed for Europe in June that year. The photograph is from this period. They arrived too late for active service, but were engaged in post-Armistice duties in France. He was discharged in England in 1919.

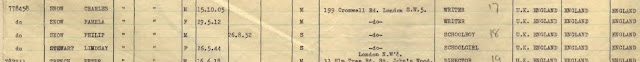

For the rest of his life, he lived in a flat in Earls Court Road from where he ran a dancing school, a highly unusual occupation for a man of his background and era. It does not seem to have been particularly successful. Although both his mother and his sister treated him more generously in their Wills than other siblings, excusing his debts, and setting up trusts to provide him with a good income, he left only £167 when he died in 1951. Surprisingly, he left this to Miss Kathleen Fricker, one of three unmarried sisters who lived in Wandsworth. Who was she? His Will had been made over 20 years earlier.

This leaves a lot of gaps and questions. He apparently had a lady friend, but was also a man’s man and adventurer. How was he able to move easily between military postings, or was he forced to? And the school of dance? He sounds every bit as dashing as the photograph suggests. Ships’ passenger lists describe him as 6 feet tall, with dark complexion, brown hair and blue eyes. What could be more arresting than a handsome, six-foot Matabeleland Mounted Policeman? I bet he looked grand in the uniform.

|

| The South African Mounted Police in 1960 probably had a similar uniform |

It is not clear what his relationship was with Kathleen Fricker, but had they wanted to marry, they would not have been able to, because he remained married to Maisie. And before blaming him for the shortness of that marriage, it is worth hearing a little more of Maisie’s story, which is even more bizarre.

Maisie Armytage-Moore was a larger-than-life character who dressed in black, smoked cigars, and loved boxing and American Indians. Three years before marrying Reginald, while still a teenager, she became friends with a notorious American stagecoach robber, Bill Miner. He taught her to ride and built her a skating rink. Another friend was a North American Indian girl, Lena Vogt, who taught her about Indian ways and the outdoors. This was later very significant. Also around this time, she wanted to elope with a Christian preacher, the George Mordecai mentioned earlier.

Three years after her short marriage, she went off to the USA with a man called Martin Joseph Murphy, a lumberjack and part-time boxer, with whom she managed a boxing troupe travelling around logging camps. She also worked for a union called International Workers of the World, which in 1919 was involved in a serious labour riot in Centralia, Washington, and she had to return to Canada. She had five children with her, presumably all born to Murphy.

Around 1927, she began to work for a lawyer called Tom Hurley, an advocate for American Indian justice. Maisie also founded ‘The Native Voice’, a publication for and about first nation people. She was still known as Armytage-Moore, but was by now with Tom Hurley. She seems not to have divorced because of her Episcopalian faith, and could not have remarried because Hurley was Roman Catholic. Maisie only married Tom Hurley after Reginald died in 1951.

Maisie became very well-known as a champion of First Nation people, and there is lots about her online. Many thought it subversive, and she and Tom were sent to prison at one point. It would certainly have appealed to Maisie’s non-conformist nature. She was clearly a headstrong woman, but also very odd.

One story tells how she inherited a casket said to contain the preserved heart of her ancestor, the first Marquess of Montrose, who was executed in 1650. She had it sent out to Canada. Her grandchildren used to open the casket, take out the heart, and play with it. Imagine them daring each other to touch it, or chasing after their friends with it. One granddaughter remembers her horror when she took it out and it broke into two pieces.

So, why did Maisie walk out of the marriage so quickly? Wild, dynamic, independent woman or ineffectual, possibly gay, dreamer? Six of one and half a dozen of the other is my guess.

Maisie’s collection of Indian art and artefacts is in the North Vancouver Museum and Archives. The heart is in the Montrose museum in Scotland.