A SEASONAL TALE

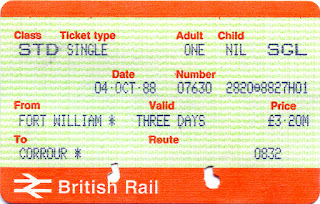

New Month Old Post: first posted 9th December, 2014. A fictional story set in a real time and place. I had recently been reading Thomas Hardy’s short stories.

We grow up, we move away, we make our lives in distant places, yet, something draws us back. We tell nostalgic tales of times past, wonder at any mention of our town on television and look for the home team football result. Even after all formal and familial ties are gone, we make special detours to pass our old homes and schools.

But not Matt Wetherell. He keeps well away. When work takes him to Hull from his home across the Pennines, he turns off and enters the city over the Humber Bridge. Anything to avoid Goole.

Fifty years ago when still in the sixth form, Matt and his friends became regulars at the Percy Arms. In those days, sixth formers in a public house would have been in serious trouble, even when legally old enough to drink. It was an abuse of privilege, squandering their opportunities while those less fortunate were cleaning railway engines or keeping the peace in Cyprus. Matt and his friends kept discreetly out of sight in the taproom and the handful of teachers who frequented the same establishment carefully stayed in the lounge so as not to notice them.

The comforts of the taproom were basic: plain walls, wooden floorboards, bench seats and bare tables, but there was always a warm fire burning. It was perfectly adequate for the main activities there: drinking, smoking, playing cards and dominoes, and telling yarns. Matt and company tested each others’ memories of the Latin fish names on the faded chart on the wall. They became familiar with the other regulars: the farmer, the garage owner and the cinema manager who always arrived late with his wife after the last show, never removed his trilby and always had a rude story to tell.

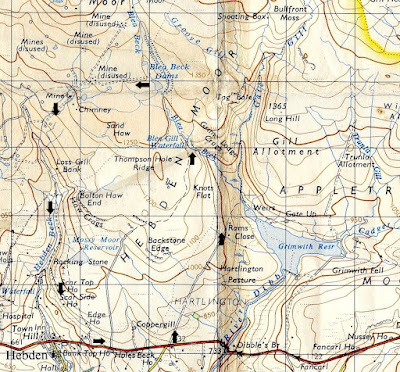

To reach the Percy Arms, Matt and his friends walked the mile or so across the fields using the track known as Airmyn Crossings. It was lonely and remote in those days before the roaring motorway was built, and a housing estate sprawled across it. It was a pleasant stroll on a warm evening, more of a challenge in wind and rain, and undeniably menacing after dark, especially where the trees and bushes joined overhead. The darkness added adventure to the walk home which was always late. Pubs were not supposed to serve drinks after half-past ten, but the landlord bent this rule a little, especially if the cinema manager was delayed. The local police knew when to be diplomatic. Sometimes, it could be nearly midnight before Matt and his friends started home along the pitch black track with several pints of John Smith’s inside them, their apprehension kept at bay by vulgar songs and loud bravado. Sometimes a couple of the group would steal ahead to hide in the bushes ready to jump out and frighten the others with piercing cries. It was rowdy, but innocuous enough compared to what some teenagers get up to nowadays.

Matt never finished his sixth form studies. Before his friends went off to university he had left school for a job in a local office, his ambition diverted by a girl friend, the accomplished and beautiful daughter of an affluent local solicitor. They made plans and imagined their future together, but much to her father’s relief, she left for university too. Despite ardent promises to remain true, she gradually drifted away. When Matt last heard of her, she was organising famine relief in Africa.

Thus, one Christmas Eve, Matt found himself alone. He decided for old times’ sake to walk the path to Airmyn. Nothing had changed. The taproom was just as it had been. The floorboards still knocked to his footsteps, the seats remained hard, the tables, bare, the fading fish were still on the wall. There were few signs it was Christmas, but the coal fire had a more cheerful glow than usual and everyone was in a happy frame of mind. Matt played dominoes with the farmer. The garage owner enquired as to his well-being. The cinema manager arrived late with his hat, wife and rude story.

When Matt eventually started back along the deserted track, a little unsteadily due to the beer inside him, it was late and an ominous fog had descended. It was thick, the kind you get when moisture from the rivers and low-lying fields conceives a dense, cold vapour that penetrates your lungs and shrouds the sight and sound of your footsteps. Matt’s shadow hung eerily in the mist around him; shapes and silhouettes moved in and out of the bushes; dark forms ahead and behind gave the impression of something approaching and then dissolving away. The only thing Matt heard was the sound of his own breathing. It intensified his unease.

Suddenly, just where the path bends beneath overhanging trees, Matt sensed something tumbling from above, as if someone was falling on him. Inches from his own face was another face, a terrifying face with hollowed-out eyes and grimacing, uneven teeth. Matt raised his arm to push it away. His hand slipped into the mouth; it felt wet and cold; his fingers scraped across rough teeth. He shuddered and screamed, and staggered sideways into the adjacent field, the surface of which lay some two or three feet below the level of the path.

Looking up from the ground, Matt realised he was alone. No one else was on the path. Yet, he was certain it had been real. His fingers were wet where they had entered the mouth, and sore where they had rubbed across the teeth. Beside him, on the ground, was something round. It took a few moments to realise it was a human skull. It had the same uneven teeth as the face that had materialised in front of him. Matt cursed. Stone cold sober, he scrambled back up to the path and ran fast to the safety of the street lights on the main road.

Rationalising afterwards, Matt decided the skull had indeed been real. He had a graze on his hand to prove it. In his drunken state, he must have fallen from the path, dislodging the skull from the loose earth at the side of the field. The rest was illusion. It had only seemed to drop from above as the ground came up towards him. He had probably covered it up again as he scrambled back up to the track. He never related the incident to anyone, and there was never any report of human remains found on Airmyn Crossings.

The following week, Matt’s employer offered him a promotion in Lancashire. It was several years before he visited the Percy Arms again. When he did, reluctantly, but necessarily because of a family function, much had changed. Outwardly, it looked the same, but inside it had become a single large, refurbished lounge. There was no sign that the taproom had ever existed. He drove there by car, but passing along Airmyn Road, he just had time to register that the route of the old Airmyn Crossings had been diverted to accommodate the new motorway.

All of this was over fifty years ago. The farmer, the garage owner, the cinema manager and his wife must be long gone.

Recently, Matt heard a tale that seemed to have some bearing on the events of that Christmas Eve of long ago. A distant cousin, Louisa, whom he knew only vaguely, visited him in the course of tracing her family history. Matt was unable to add much to her findings, but she told him a tale that had been passed down to her grandmother from her grandmother’s grandmother.

The name, Matt, or Matthew, had run through the Wetherell family for generations. An earlier Matthew had been born in a village many miles away to the North. That Matthew had worked on the lands of the Northumberland estates belonging to the Percy family. One summer he had transgressed unwritten social expectations by becoming too familiar with the daughter of the incumbent of the local Parish. To prevent the friendship developing into anything more serious, it had been arranged that Matthew would be moved away to other lands owned by the same family in distant Airmyn. Matthew’s brother Mark had to move with him for no reason other than that he was Matthew’s brother. In due course, the news arrived that the vicar’s daughter of whom Matthew had been so fond, had married a tea trader and moved to the colonies. Matthew, distressed, took to wandering like a tramp in the woods and fields. He disappeared one Christmas and nothing was heard of him again.

More happily, Matthew’s brother, Mark, remained in Airmyn. He married and had a large family. He was the ancestor of both the present day Matt and his distant cousin, Louisa. If you care to look in the Airmyn Parish registers for the early years of the nineteenth century, you will find mention of a Mark Wetherell, servant in husbandry, son of John and Mary Wetherell of Melsonby, which is in North Yorkshire, near Richmond.

The exact location of Matt’s disturbing experience that dark Christmas Eve, must now be buried beneath the Eastbound carriageway of the M62 motorway. Strange things happen there. Engines misfire, sudden gusts of wind cause vehicles to swerve, drivers slow down for no apparent reason. You should concentrate and take extra care there, especially on Christmas Eve. Matt Wetherell avoids it like it was haunted.

.jpg)