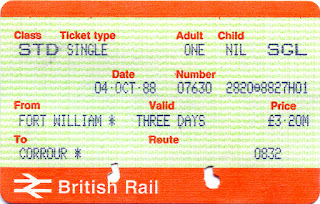

My first compass, from 1973. And I still have its 24-page instruction leaflet.

The leaflet goes into great detail, enough to enter an orienteering competition, but I used the compass mainly to check I was heading roughly in the right direction. When you are walking the twenty-five miles through the mountains from Rannoch to Fort William in the Scottish Highlands, the last thing you want is to go wrong at the high watershed and somehow find yourself miles astray at Kinlochleven. I suppose most would use a SatNav now.

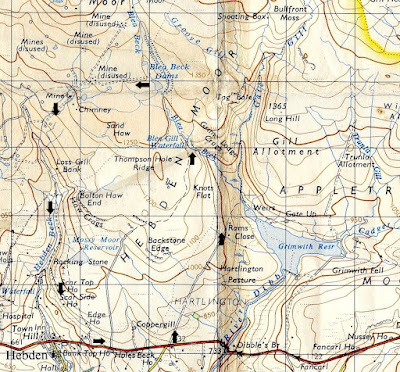

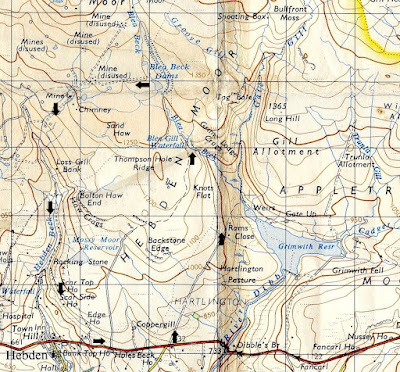

Another brilliant walk was around the hidden, Blea Gill Waterfall near Grassington in Yorkshire. You follow the track along the Western side of Grimwith Reservoir (since considerably enlarged) to Blea Beck, and then climb to the top of the waterfall to Grassington Moor. A circular anti-clockwise route takes you back via Hebden Beck to the starting point on the B6265 road.

|

| Route around Blea Gill Waterfall (1967 1-inch map) |

It was wild above the waterfall, very boggy, with few obvious tracks. There were centuries-old, disused lead mine workings, chimneys, shafts, and spoil heaps, a strangely beautiful landscape of industrial desolation, deserted by the legions of miners that once toiled there. You saw no one else all day, and without a compass it would have been easy to lose your bearings. Proper walking. I am told it has now been cleaned up with signposts, notice boards, and warnings not to fall down the concealed mine shafts.

|

| Blea Gill Waterfall, 1974 |

|

| Grassington Moor now |

I then looked for routes needing more precise compass work. I remember walking with friend Neville up to Alport Moor from Howden Reservoir in the Derbyshire Dark Peak. The ascent passes through dense evergreens before reaching open moorland, which levels out gradually, curving up so you cannot see the top until almost there. Neville looked dubious when I said the Alport Moor trig point was a little way straight ahead, and indeed there it was. He had complete faith in my map reading after that, often misplaced.

We also liked to cross the Derbyshire moorland plateau of Kinder Scout, from Fair Brook to Kinder Downfall. I wrote about it here. It is not far across, but the maze of deep, watery, peat ridges and trenches known as hags and groughs, twisting and turning in all directions, make it impossible to keep to a straight line. All distant features are below the horizon, so there is nothing you might aim towards. Unless you check your compass every few yards you go hopelessly off-course.

Navigating With The Compass

From the top of Fair Brook to Kinder Downfall you follow a bearing of about 255 degrees, but you do not really need to know about bearings. All you have to do is set the compass using the map, and then follow it. Well, that is how I do it.

The needle of the compass points red to the North. It swivels inside a black dial, which can be manually rotated on a transparent base plate. The base plate has a large arrow pointing away from the needle.

You place the compass on the map with the large arrow pointing roughly in the direction you want to go, and then slide it so that one of the long edges of the base plate passes through both your current position and your target destination, e.g. from the top of Fair Brook to Kinder Downfall as circled in yellow in the photograph. You then rotate the dial so that North on the dial matches the grid lines on the map. There are lines inside the dial to help with this. It does not matter which way the map or the magnetic needle are pointing at this stage.

|

| Setting the compass: Fair Brook to Kinder Downfall |

You can then put the map away for a while. Stand up and hold the base plate level with the large arrow pointing ahead of you. Slowly turn round until the red needle lines up with North on the dial, and walk straight ahead. It helps to choose a distant feature to aim towards, if one can be seen.

There is a lot more to it, but I usually find this sufficient. You could adjust for the difference between Magnetic North and Grid North, but over short distances it probably does not matter much, so I am not going into that. It makes only about 2 degrees difference at present, although in past decades it has been as much as 10. It slowly changes. It is also worth mentioning that map grids do not always point to True North, but, again, it does not really matter. I could explain these different kinds of North, but do you really want to know?

The 24-page leaflet explains all this in greater detail. I have archived a PDF copy here, in case you are nerdy enough to be interested.

As mentioned at the start, this was my first compass. I later bought a new, supposedly more accurate mirror compass, but never got the hang of it. I simply fold out the mirror and use it in the same way as the old one. I believe that for greater accuracy you can read the needle through the mirror, and look at objects through the hole and the notch. I am told that you can even measure heights, if so inclined. But I would rather enjoy the countryside than study for qualifications in surveying. At least the new compass fits neatly into your trouser pocket without any sharp corners to castrate you when you sit down. And the mirror allows you to check your face is still perfect after a long day out in the wind and rain.

.jpg)