My vision issues make reading and participating in comment quite challenging just now, but I continue to enjoy your blog posts which the computer reads for me.

Today, I want illustrate life's vicissitudes through the story of my mother's lifelong friend Doreen. They are the kind of things we like to pretend do not happen.

Shortly after my parents married, they rented the two-bedroomed terraced house where I spent my first years. It needed thorough cleaning, so Mum busied herself scrubbing floors, washing windows, scouring the kitchin, sweeping the yard and hanging curtains. I can imagine the hot, damp smell of soap flakes, coal tar soap, scouring powder and disinfectant. There were few detergents. She had escaped her claustrophobic village and mother for her own little house in town, where she built a new life and blossomed.

In the back-bedroom of the house across the lane at the rear, a woman of similar age lay in bed-rest at her mother-in-laws', heavily pregnant with twins. She watched my mother at work and wondered who was this energetic and pleasant-looking young woman she had never seen before. Her mother-in-law came across to make contact, and Mum went across to meet Doreen. They had lots in commom and talked for hours.

They became lifelong friends. We visited each others' houses all the time. I called her Aunty Doreen. I have a lovely photograph of my pregnant (with me) Mum with Doreen, her husband and the twins walking along the promenade on a sunny day-trip to the seaside. They are all laughing and happy.

A few hears later we moved to a bigger house in the next street, so saw a little less of each other, but still visited often. It did not therefore surprise me on returning from school one afternoon to find the twins at our house. They were a girl and a boy then aged around ten. I was around seven. What I did not know was that they were there because their father had been taken seriously ill at the mill where he worked. He had had a massive heart attack. After a time someone knocked on the door and my mother sat the twins down at the table because she had something to tell them. "Your daddy's died" she simply said. It must have been almost impossible to say. They both burst into floods of tears. I didn't really understand but knew it was awful. People at the mill remembered how disturbing it was to see his overalls and shoes still at his peg. His body lay at rest at hone in the front room until the funeral. Doreen was still in her thirties.

But life goes on. With support from relatives, friends and neighbours Doreen brought up the twins into teenagers. A few doors along the street lived Maurice, a railway engine driver who had lived alone since his parents had died a few years earlier. He was a good-looking, gentle giant of a man, shy and quiet. The twins thought him wonderful and he became like an uncle who played with them. He formed a close friendship with Doreen and eventually proposed. Doreen was forty-two, Maurice about thirty-four.

"But he's so much younger than me," Doreen told by mother.

"Gerrim married," Mum replied.

So she did, with my mother looking radiant and lovely as Matron-of-Honour. She had never been a bridesmaid before.

The photographs show a happy day, although as I have seen in other families including ly owm, her late husband's mother does not look entirely behind the idea. The marriage worked and lasted over thirty years.

On his days off, Maurice liked to do odd-jobs, and I sometimes found him round at our house quietly washing the windows.

Then at around the age of sixty, Doreen became very ill with bowel cancer.

"They'll be taking me out of here in a box," she told my mother visiting her in hospital. And we all thought that was true.

And yet, against all the odds, she survived. She had an ileostomy operation and it was successful. It was my mother who died two years later of breast cancer and Doreen survived her by twenty years before falling into old-age and dementia. Maurice lived on for another ten years.

To get through life without encountering such dreadful ups and downs is very fortunate. For the rest of us that do, I don't know how do manage to cope. We must be very resiliant. It's not all rosy, is it!

Google Analytics

Showing posts with label biography. Show all posts

Showing posts with label biography. Show all posts

Wednesday, 22 February 2023

Doreen

Tuesday, 1 December 2020

Ray Gosling’s Goole

(First posted 15th October 2017. The YouTube videos linked below are quite long. I don’t expect many will want to watch them through.)

|

| Gosling’s Travels: Goole (1975, 26 minutes) |

In 1975, the radio and television broadcaster, Ray Gosling, made a film about Goole: a place I used to know well. The inhabitants were appalled. They had been looking forward to a film about a pleasant little town on the banks of the Ouse, with friendly folk in homely homes, about canals and railways, brave mariners who sailed the North Sea, the strange salt and pepper pot water towers, and the proud rise of a town from nothing to one of the country’s busiest ports in less than a hundred years: the story of the port in green fields.

But Ray Gosling was never going to stick to that. He homed in on the eccentric linguist who sought out foreign sailors to practise his Russian, businessmen who looked shifty and evasive, dockers who appeared scheming and workshy, the mysterious world of pigeon keepers, and, most embarrassing of all, the star turn, some young ladies who also liked to consort with foreign seamen, although not to practise their language skills. Goole: working-town low life in ragged abundance.

Watching again on YouTube, I see the problem. Right from the start, he goes for the jugular:

I’m walking the streets of a flat little town in Yorkshire that most of you will never have heard of: Goole. And those who do know where it is, between Doncaster and Hull, have nicknamed it Sleepy Hollow, because nothing has ever happened here that’s made the headlines in a newspaper. The place has no history worth putting into history books, and they don’t really manufacture anything.You might say: “What did you expect?” It was what Ray Gosling did. He was different from other broadcasters. He was cheeky and a bit common, working-class with an East Midlands accent, a university dropout, C-stream and proud of it. He made films about the little things of life, to him more important than the big things: caravans, allotments, sheds, the seedy, the left behind, the small-scale concerns of ordinary people. He was one of them. He wrote about them, ran things and campaigned for them.

The film is pure genius. He had seen the times they were a-changin’ long before Bob Dylan. He had tried to help the lively working-class community of St. Ann’s in Nottingham when the local council wanted to flatten and redevelop the whole district, but the community was lost in the end. He could see that Goole’s canal trains of coal-loaded compartments known as ‘Tom Puddings’, hydraulically hoisted into the air and tipped into the holds of ships, were nearing their end. Goole was a working museum that could not last, no more than the well-meaning vicar and police chief in the film, gullible anachronisms innocently trying to set up a wholesome mariners’ club not run by mariners. It was never going to supplant the Dock Tavern.

He had read On the Road and seen Rebel Without a Cause and The Wild One (a film banned in Britain) and understood the implications. He saw change in the hearts of young people rejecting their fuddy-duddy parents’ expectations. His autobiographies, Sum Total and Personal Copy are fascinating memoirs of the fifties and sixties. “We were the first generation to be able to busk with our lives” he reflected in 2006 in one of his last films, Ray Gosling OAP. And as he sat waiting for his cluttered Mapperley house to be forcibly sold due to bankruptcy, unable to move around the heaped accumulations of a lifetime’s work: piles of files, mountains of books, scattered nick-nacks; he said:

All my life, I’ve known we are what we collect, what we pick up, so my room with all the detail I’ve kept is what made my work, it was important, to me. The silly nick-nacks are not just nick-nacks, and they’re not silly.That is truly uplifting to hoarders like me: the glorious antithesis of decluttering.

| Ray Gosling OAP (2006, 59 minutes) |

I'll leave the last word to Ray himself, part of an article in the TV Times in 1975:

... I don’t think facts always tell the truth. And I’m not a promotion man for God, Queen and the Ruling Class in Britain Beautiful – but we do search for the good in a place. And try to film what people naturally do. Try to avoid dwelling on obvious eccentrics, though that’s difficult. We are such an individual fruit and nutcase lot. I’m not hawking any pet philosophy or seeking hidden meanings. The films are simply place-tasters.

I don’t know what you’re going to make of Goole. People live nearby refer to it as Sleepy Hollow, because nothing ever happens in Goole. That’s why I went. It’s one of the most forgotten places of England. Britain’s most inland port, 50 miles from the sea. Just as Bath doesn’t make enough of its spa water, Goole doesn’t make enough of its dirty canal water. Still it is the 11th port of the land. Behind the parish church, you can see hanging from the jib of a crane, Britain’s balance of payments. Steel: in and out. Russian timber imported. We got turfed-off a Russian boat, camera and all – nicely, but firmly. And Goole exports: coals for every purpose.

The great local row was in the pigeon club. Should the birds be flown, next season, from north to south? Opinion divided. I like Goole, I do hope I’ve done it justice.

There was a nice man we wanted to film there; Albert Gunn, dental mechanic, pigeon racer and performer in the amateur Kiss Me Kate at the Grammar School – but Albert was ill, so we couldn’t.

That’s the problem I find filming as against writing. With pictures we have to prove it. Our folks have got to perform in front of the camera.

Wednesday, 1 July 2020

Uncle Jimmy

(New month old post) First posted 28th June, 2015. 1,600 words)

My mother always said it would have been better if Uncle Jimmy had been brought up as a girl. When I was older, she added: “You see, he didn’t develop properly when he was a little boy.” She also said: “His sister was completely the other way round.”

Uncle Jimmy was not really an uncle or indeed any relative at all. He attached himself to the family just before the First World War when he crossed the Pennines to take a job in the local branch of the clothing and furniture retailer where my grandfather worked. As Jimmy had nowhere to stay, my grandfather took him home and asked whether they could put him up for a time. Jimmy soon found his own accommodation and later, perhaps surprisingly, a wife, but he remained a close friend of the family for the rest of his life. He appears in no end of our family photographs: a surrogate uncle.

“A jolly little fat man with a high voice,” is how my brother remembered him, “Uncle Jimmy Dustbin,” not his real name but a pretty good homonym. He had been slightly built in his youth. His army attestation papers show he was five feet two inches tall (157 centimetres) with just a 31 inch chest (79 centimetres). He must have suffered terribly at the hands of childhood bullies and may have left his native Cheshire to begin life afresh where nobody knew him.

He tried to join up for war service six times but was rejected because of poor physique. After being accepted at the seventh attempt, he found himself passed rapidly from regiment to regiment like a bad penny. He first joined the York and Lancasters, but on mobilization was transferred back into the army reserve to grow and gain strength. He was mobilized again eight months later but within another six months had been transferred to the Yorkshire Regiment. He managed three months there before being compulsorily transferred to the 5th (Cyclist) Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment. This was part of the Army Cycle Corps used for coastal defence work inside the United Kingdom. His situation seems to have improved for a while because he qualified as a signaller, but within a year his difficulties had returned and he was transferred to the West Yorkshire Regiment. A month later he was judged physically unfit for war service, permanently discharged, issued with an overcoat and sent home. Jimmy’s war was thus based in such far flung locations as Durham, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Hartlepool and Aldershot. At no time did he see service in France.

Jimmy married while still in the army. He was almost twenty-five and his wife, let’s call her Beatrice, almost twenty-seven. They remained together for forty-seven years until she died. For some years they looked after one of Beatrice’s nephews but were unable to have children of their own. What Beatrice expected is not entirely clear, although she did once say to my grandmother she had little idea of what was supposed to happen on wedding nights, and remained just as mystified afterwards because nothing did. She seemed content to have settled for a marriage of crafts, hobbies and companionship.

Jimmy and Beatrice became grocers. Beatrice’s widowed mother had a corner shop in one of the town’s dense grid of terraced streets, so Jimmy moved in to help with the shop and eventually became the nominal owner. Beatrice did most of the work as Jimmy always found plenty of other things to occupy him. He became a churchwarden along with my grandfather, and a Sunday School teacher. He collected glassware and was a natty dresser, but his greatest joy was motoring. He advertised his services as an express courier and hence became one of the first in town with a private telephone and private motor car.

His first car was a 1922 ‘Bullnose’ Morris. My father said that whenever his own family took their annual week’s holiday, in those days always to one of the Yorkshire coastal resorts, Jimmy would arrive in his car to join them for a day. On other occasions he would take my father and his sister on trips to the coast. They had a clear memory of one happy outing when they drove under the arched bridge between Bridlington and Filey where the railway embankment crosses the road, when Jimmy jokingly forbade them to shout as they passed through, which of course they did, their high spirited voices echoing back to them in the open-topped car. On another occasion he took my aunt for a ride in an aeroplane at Speeton airfield.

In later years, after my grandparents had died, Jimmy and Beatrice became surrogate grandparents, especially to my cousins. In fact they remember Uncle Jimmy and Aunty Beatrice by far the more clearly. They spent hours reading, singing, playing games and looking after them. Beatrice shared her jigsaw puzzles and taught them to crochet. Jimmy was the only one with the patience to feed to my elder cousin her breakfast in the way she wanted, one cornflake at a time, even though he was supposed to be at work in his shop. My uncle described him, in bemused admiration, as the only man he knew who had managed to get through life without working.

Eventually Jimmy and Beatrice retired from the grocers shop and moved for around fifteen years to a large house in a green and leafy part of town overlooking the river, but after Beatrice died Jimmy moved back to the same terraced street they had lived in previously, and was very lonely and unhappy. It was by then the nineteen-sixties. Society was changing and the street had lost its sense of community. Jimmy was a frequent visitor both to our house and my cousins’, arriving in his car, always a Morris. He showed a lifelong loyalty to the Morris marque.

Jimmy lived to eighty-one. During his last illness, unable to eat, he turned to my aunt for help and she told him she thought he should be in hospital. “All right,” he said, “but let’s have a cig first. We’ll have one of yours.” It was his last one. My aunt, a nurse, looked after him during his final days, and in dealing with his most intimate needs was disturbed to observe just how incompletely developed he was, “more female than male” she later confided.

Again, we were spared the details but some years ago, thirty five years after his death, I looked at Jimmy’s army service record in an online genealogy resource. It included Army Form B, 178A, Medical Report on a Soldier Boarded Prior to Discharge or Transfer to Class W, W(T), P or P(T), of the Reserve. Across the various sections of the form I was dismayed to read:

Feminism. Undesirability of retaining with hommes militesque. Congenital. Poor physique from infancy and puberty. Pain with equipment. Tastes and habits male. Married 12 months, no children. Enlarged breasts, female type. Poor general physique. R. testicle incompletely descended. Penis abnormally short. Embryonic pocket in scrotal line. Voice female. Was rejected 6 times on grounds of physique and accepted the 7th time. Discharge as permanently unfit.

And what of his sister, a back-slapping sporty woman who my mother said should have been brought up a boy. She also married but after several years her husband was granted an annulment. She then became a champion ladies golfer who represented her county. It was said she astonished other golfers by driving consistently long distances from the men’s tees. She spent her life organising competitions and golfing associations, and was still playing in veterans’ tournaments at the age of seventy. Did she have a similar congenital condition? We can now easily see that there were four other siblings who survived into adulthood. What about them? They seem to have produced few children and grandchildren.

Today, abnormal sexual development is much better understood than when Jimmy and his sister were born in the eighteen-nineties. For example, research into sex hormones did not make any real progress until the nineteen-thirties. The various conditions are now handled sympathetically and have a range of treatments. How very different from when Jimmy and his sister were young. What desperately miserable and lonely episodes they must have endured. Yet to us, Uncle Jimmy always seemed happy and jovial. He was kind and thoughtful, very much loved. I think we must have given him something of the family life he would never otherwise have had.

There was one last thing we could do for him. It was saddening to see his medical record on public display. Although British Army First World War service and pension records, if they survive, are now accessible through online genealogical resources, medical records are usually confidential. We wrote to the National Archives at Kew to ask whether it was possible, on the grounds of respect and decency, to remove the medical report from the online resource, to which they agreed. Genuine researchers can still go to Kew, look up the microfiche copy of his army service record, and find Army Form B178A included, but in the online version it is no longer there.*

In wanting to tell Jimmy’s sad and touching story, albeit with names changed, and in quoting from the form, I hope I am not indulging in the kind of prurience we want to avert.

* Unfortunately, since the original post, other genealogical resource providers have been permitted to scan the documents and it is now visible on several sites.

The life of an intersex man born in the 1890s

My mother always said it would have been better if Uncle Jimmy had been brought up as a girl. When I was older, she added: “You see, he didn’t develop properly when he was a little boy.” She also said: “His sister was completely the other way round.”

Uncle Jimmy was not really an uncle or indeed any relative at all. He attached himself to the family just before the First World War when he crossed the Pennines to take a job in the local branch of the clothing and furniture retailer where my grandfather worked. As Jimmy had nowhere to stay, my grandfather took him home and asked whether they could put him up for a time. Jimmy soon found his own accommodation and later, perhaps surprisingly, a wife, but he remained a close friend of the family for the rest of his life. He appears in no end of our family photographs: a surrogate uncle.

“A jolly little fat man with a high voice,” is how my brother remembered him, “Uncle Jimmy Dustbin,” not his real name but a pretty good homonym. He had been slightly built in his youth. His army attestation papers show he was five feet two inches tall (157 centimetres) with just a 31 inch chest (79 centimetres). He must have suffered terribly at the hands of childhood bullies and may have left his native Cheshire to begin life afresh where nobody knew him.

He tried to join up for war service six times but was rejected because of poor physique. After being accepted at the seventh attempt, he found himself passed rapidly from regiment to regiment like a bad penny. He first joined the York and Lancasters, but on mobilization was transferred back into the army reserve to grow and gain strength. He was mobilized again eight months later but within another six months had been transferred to the Yorkshire Regiment. He managed three months there before being compulsorily transferred to the 5th (Cyclist) Battalion of the East Yorkshire Regiment. This was part of the Army Cycle Corps used for coastal defence work inside the United Kingdom. His situation seems to have improved for a while because he qualified as a signaller, but within a year his difficulties had returned and he was transferred to the West Yorkshire Regiment. A month later he was judged physically unfit for war service, permanently discharged, issued with an overcoat and sent home. Jimmy’s war was thus based in such far flung locations as Durham, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Hartlepool and Aldershot. At no time did he see service in France.

Jimmy married while still in the army. He was almost twenty-five and his wife, let’s call her Beatrice, almost twenty-seven. They remained together for forty-seven years until she died. For some years they looked after one of Beatrice’s nephews but were unable to have children of their own. What Beatrice expected is not entirely clear, although she did once say to my grandmother she had little idea of what was supposed to happen on wedding nights, and remained just as mystified afterwards because nothing did. She seemed content to have settled for a marriage of crafts, hobbies and companionship.

Jimmy and Beatrice became grocers. Beatrice’s widowed mother had a corner shop in one of the town’s dense grid of terraced streets, so Jimmy moved in to help with the shop and eventually became the nominal owner. Beatrice did most of the work as Jimmy always found plenty of other things to occupy him. He became a churchwarden along with my grandfather, and a Sunday School teacher. He collected glassware and was a natty dresser, but his greatest joy was motoring. He advertised his services as an express courier and hence became one of the first in town with a private telephone and private motor car.

|

| Uncle Jimmy with his 1922 ‘Bullnose’ Morris on an outing to Bridlington in 1928. In the car (right to left) are my father (in cap), his sister (in bonnet) and Jimmy’s wife’s nephew. |

His first car was a 1922 ‘Bullnose’ Morris. My father said that whenever his own family took their annual week’s holiday, in those days always to one of the Yorkshire coastal resorts, Jimmy would arrive in his car to join them for a day. On other occasions he would take my father and his sister on trips to the coast. They had a clear memory of one happy outing when they drove under the arched bridge between Bridlington and Filey where the railway embankment crosses the road, when Jimmy jokingly forbade them to shout as they passed through, which of course they did, their high spirited voices echoing back to them in the open-topped car. On another occasion he took my aunt for a ride in an aeroplane at Speeton airfield.

In later years, after my grandparents had died, Jimmy and Beatrice became surrogate grandparents, especially to my cousins. In fact they remember Uncle Jimmy and Aunty Beatrice by far the more clearly. They spent hours reading, singing, playing games and looking after them. Beatrice shared her jigsaw puzzles and taught them to crochet. Jimmy was the only one with the patience to feed to my elder cousin her breakfast in the way she wanted, one cornflake at a time, even though he was supposed to be at work in his shop. My uncle described him, in bemused admiration, as the only man he knew who had managed to get through life without working.

Eventually Jimmy and Beatrice retired from the grocers shop and moved for around fifteen years to a large house in a green and leafy part of town overlooking the river, but after Beatrice died Jimmy moved back to the same terraced street they had lived in previously, and was very lonely and unhappy. It was by then the nineteen-sixties. Society was changing and the street had lost its sense of community. Jimmy was a frequent visitor both to our house and my cousins’, arriving in his car, always a Morris. He showed a lifelong loyalty to the Morris marque.

Jimmy lived to eighty-one. During his last illness, unable to eat, he turned to my aunt for help and she told him she thought he should be in hospital. “All right,” he said, “but let’s have a cig first. We’ll have one of yours.” It was his last one. My aunt, a nurse, looked after him during his final days, and in dealing with his most intimate needs was disturbed to observe just how incompletely developed he was, “more female than male” she later confided.

Again, we were spared the details but some years ago, thirty five years after his death, I looked at Jimmy’s army service record in an online genealogy resource. It included Army Form B, 178A, Medical Report on a Soldier Boarded Prior to Discharge or Transfer to Class W, W(T), P or P(T), of the Reserve. Across the various sections of the form I was dismayed to read:

Feminism. Undesirability of retaining with hommes militesque. Congenital. Poor physique from infancy and puberty. Pain with equipment. Tastes and habits male. Married 12 months, no children. Enlarged breasts, female type. Poor general physique. R. testicle incompletely descended. Penis abnormally short. Embryonic pocket in scrotal line. Voice female. Was rejected 6 times on grounds of physique and accepted the 7th time. Discharge as permanently unfit.

And what of his sister, a back-slapping sporty woman who my mother said should have been brought up a boy. She also married but after several years her husband was granted an annulment. She then became a champion ladies golfer who represented her county. It was said she astonished other golfers by driving consistently long distances from the men’s tees. She spent her life organising competitions and golfing associations, and was still playing in veterans’ tournaments at the age of seventy. Did she have a similar congenital condition? We can now easily see that there were four other siblings who survived into adulthood. What about them? They seem to have produced few children and grandchildren.

Today, abnormal sexual development is much better understood than when Jimmy and his sister were born in the eighteen-nineties. For example, research into sex hormones did not make any real progress until the nineteen-thirties. The various conditions are now handled sympathetically and have a range of treatments. How very different from when Jimmy and his sister were young. What desperately miserable and lonely episodes they must have endured. Yet to us, Uncle Jimmy always seemed happy and jovial. He was kind and thoughtful, very much loved. I think we must have given him something of the family life he would never otherwise have had.

There was one last thing we could do for him. It was saddening to see his medical record on public display. Although British Army First World War service and pension records, if they survive, are now accessible through online genealogical resources, medical records are usually confidential. We wrote to the National Archives at Kew to ask whether it was possible, on the grounds of respect and decency, to remove the medical report from the online resource, to which they agreed. Genuine researchers can still go to Kew, look up the microfiche copy of his army service record, and find Army Form B178A included, but in the online version it is no longer there.*

In wanting to tell Jimmy’s sad and touching story, albeit with names changed, and in quoting from the form, I hope I am not indulging in the kind of prurience we want to avert.

* Unfortunately, since the original post, other genealogical resource providers have been permitted to scan the documents and it is now visible on several sites.

Saturday, 6 July 2019

Mrs Quackworth (reposted by Smorgasbord Blog Magazine)

Sally Cronin’s fourth and final selection from my archives for her Smorgasbord Blog Magazine is a post from a year ago about a next-door neighbour we nicknamed Mrs. Quackworth. I don’t know how she ever put up with our muck-chucking fights across her garden.

It has been interesting to see which items Sally would select, it being hard to know for sure which posts others particularly like. Had I been asked to select four myself they might have been completely different. Thanks, Sally, for the many hours you must have spent looking back through our archives - not just mine but all the others too.

The Smorgasbord repost invitation is here

The reposted post is here

Until I was ten or eleven I had to share a bedroom with my younger brother. We were sent to bed at the same time, which meant he got to stay up later than I had at his age and I had to go sooner than I thought I should.

It was not even dark in summer. We could hear Timmy from next door-but-one bumping along the pavement on his trolley, made from a long board and some old pram wheels. We were in bed but he was still playing out at ten o’clock at night. That was really unfair. He was two years younger than me.

Downstairs we could hear the next-door neighbour talking with our parents. She sounded like a duck, as did her name ...

Read original post (~1200 words)

It has been interesting to see which items Sally would select, it being hard to know for sure which posts others particularly like. Had I been asked to select four myself they might have been completely different. Thanks, Sally, for the many hours you must have spent looking back through our archives - not just mine but all the others too.

The Smorgasbord repost invitation is here

The reposted post is here

Mrs Quackworth

|

| With the Operatic Society around 1920 |

It was not even dark in summer. We could hear Timmy from next door-but-one bumping along the pavement on his trolley, made from a long board and some old pram wheels. We were in bed but he was still playing out at ten o’clock at night. That was really unfair. He was two years younger than me.

Downstairs we could hear the next-door neighbour talking with our parents. She sounded like a duck, as did her name ...

Read original post (~1200 words)

Saturday, 23 March 2019

George Gibbard Jackson

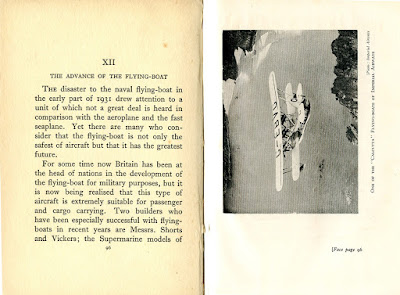

Amongst my dad’s childhood books are two volumes in matching red bindings: The Splendid Book of Aeroplanes and The Splendid Book of Steamships by G. Gibbard Jackson. My dad’s name and address are inscribed inside both of them in my grandfather’s neat hand, together with the dates they were bought: the 25th and 26th of July, 1932. The steamships volume seems to have been bought the very next day on the strength of the aeroplanes one.

If so, it was a mistake. The Splendid Book of Aeroplanes is indeed a splendid book, packed with splendid tales, from the pioneers of flight right up to the nineteen-thirties. In contrast, the steamships book is unremarkable and prosaic, little more than a descriptive record.

For example, until I read the aeroplanes book, I had never heard of Mrs. Victor Bruce who made the first flight from London to Tokyo in 1930; a riveting story of forced landings, sheltering with desert tribesmen on the shores of the Persian Gulf, and contracting malaria in the Mekong jungle. This was just one of her many exploits in a life of derring-do. Incredibly, she lived until 1990. Why is she not as famous as Amy Johnson or the Campbells?

Then there is the moving story of Saloman Andrée’s balloon expedition to the North Pole in 1897, which failed to make the expected progress. The explorers despatched their last messenger pigeon, then nothing further was known of them until over thirty years later when their remains, diaries and exposed photographic plates were found by chance. They had been forced to land on the ice where they survived for over three months. The discovery of their final camp in 1930 was a global sensation.

|

| George Gibbard Jackson (1878-1935) |

Who was this prolific writer that few today will have heard of? A little research reveals that when he died, George Gibbard Jackson (1878-1935) was postmaster at Fareham, Hampshire. He had joined the postal service in his native Warwickshire, and worked his way up from the position of sorting clerk. Before Fareham he had spent several years as postmaster at Cobham, Surrey. He married twice, first to telegraphist Kate Emery in Coventry in 1901, and then, after Kate died, to Mabel Elizabeth Millington in Stivichall, Coventry, in 1915. He had four sons, one of whom died in childhood.

So writing was really a sideline. How could someone with a full-time job, bringing up a family between the wars in small-town southern England, find time to research and write so many books? Did his job have slack periods during the daytime? Did he spend all his spare time writing and researching? Did he neglect his family?

What about resources? In a previous post about research before the internet, I was at least referring to research in well-resourced university settings. Gibbard Jackson would have had to rely mainly on local libraries, newspapers, home encyclopaedias and similar works of reference, possibly books borrowed by post from national libraries, and maybe an occasional visit to larger resources in London or Southampton.

For example, he might have used Encyclopedia Britannica or Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia. Arthur Mee says quite a bit about the early days of flight – the Wright Brothers and so on – and while it makes only the briefest reference to the mystery of Andrée’s expedition, the newspapers were full of it in 1930 and 1931 after their final camp was discovered. Similarly, newspapers closely followed Mrs Victor Bruce’s flight during September, October and November, 1930. These secondary sources would have been sufficient for a writer of cracking tales, like Jackson, to be able to put together books for boys. And possibly his Isle of Wight book was planned on holiday. Only when you begin to look at the detail that is now available on the internet do you discover the omissions and deficiencies. For example, Jackson includes none of the photographs that emerged from the plates found in Andrée’s final camp.

He must have been pleased with his achievements. Perhaps he even made a bit of money from his writing – he was comfortably well-off when he died. But it’s not the kind of writing I would want to do for long. It’s too much like work.

Some of Jackson’s books are now accessible in full-text format, such as The Splendid Books of Engineering, Locomotives and Steamships, but so far there seems to be no online version of the aeroplanes book.

https://archive.org/details/splendidbookoflo00jackuoft/page/n5 (locomotives)

https://archive.org/details/splendidbookofst00jackuoft/page/n5 (steamships)

https://archive.org/details/splendidbookofen00jackuoft/page/n5 (engineering)

Wednesday, 25 July 2018

Mrs. Quackworth

|

| With the Operatic Society around 1920 |

It was not even dark in summer. We could hear Timmy from next door-but-one bumping along the pavement on his trolley, made from a long board and some old pram wheels. We were in bed but he was still playing out at ten o’clock at night. That was really unfair. He was two years younger than me.

Downstairs we could hear the next-door neighbour talking with our parents. She sounded like a duck, as did her name.

“Mrs. Quackworth,” I quacked in my best duck voice.

“Mrs. Ackworth,” Martin corrected me.

“Mrs. Quackworth.”

“Mrs. Ackworth,” he said more loudly.

“What’s a quack worth?”

“MRS. ACKWORTH” he yelled, lengthening each syllable as he shouted.

“MIIISSIIIS AAAAAACK WORRRRTH.”

Downstairs, the conversation stopped.

“Why is Martin calling me?”

“Shut up and go to sleep,” mother shouted up the stairs.

“That boy’s spoilt!” Mrs. Ackworth said.

* * *

I don’t know how she put up with us. We would run around, yelling at the tops of our voices:

“WHAT A GOAL!”

“FOUL! SEND HIM OFF!”

“WHOAAAAAAA! YEEEAAAYYY! WHEEEEEE!”

The ball rattled against the fence, thudded into her French windows, bounced across her garden and flattened her plants. We climbed over her rockery and ran across the lawn to retrieve it leaving a trail of dislodged stones and scuff marks.

We had muck-chucking battles with Timmy whose house was the other side of hers, depositing debris and detritus across her path. She rarely complained as she swept it up. One day we used blackberries as ammunition, stolen from the allotments near the railway, too bitter to eat. Most went astray, leaving lasting purple stains on her green shed. Stray brambles grew around her garden for some years afterwards.

I was six when we moved in next door. Mrs. Ackworth seemed ancient, but she would still have been only in her fifties. She had a deep, cultured, musical voice which had for several years gained her leading contralto parts with the local operatic society, although it had since been ruined by smoking – giving a duck sound. In her day, she had sung all around Yorkshire. Newspapers had said she was one of the best contraltos in the county. She listened to classical music on the wireless, talked about opera and the arts, and helped with the local Conservatives. The effect was formidable. She was always “Mrs. Ackworth”, never “Ethel”. People thought her fearsome.

Despite more than a twenty year age difference, she struck up a close friendship with our mother who had the knack of taking people as she found them.

“She only came from a fish and chip shop,” mother told us when we said she frightened us and asked why they were always in and out of each others’ houses, “and it’s lonely in a house on your own.”

Mrs. Ackworth had lived there the thirty years since her marriage, but her husband had died just a few months later leaving her with little means of support. Male admirers quickly gathered to help, admirers of her voice you understand, especially a wealthy property owner, himself married and twenty-eight years her senior, who set her up with a small milliners shop. She had been at school with his eldest daughter. It was said that during the nineteen thirties, when cars were rare, there would be only one in the street, her benefactor’s car, parked late at night outside her house. There were rumours they had toured Europe together. When he died he left her a considerable sum of money but his family somehow managed to deprive her of it.

Mrs. Ackworth used to watch us from the kitchen window as we played in the garden. It felt intrusive, but I know now she was thinking about the children she never had. She was distraught when we moved again after a decade or so, but we kept in touch through the years, through the inevitable succession of marriages, births and deaths. In effect, she became a surrogate grandma.

“You’d better go see Mrs. Ackworth,” my brother and I were told when we were home, and so we did, to sit and be criticised beside her coal fire and look out through her French windows at the rockery, lawn and shed. Later, we took our wives, and then our children. The house still had all the original nineteen-twenties fixtures, with kitchen cupboards and fireplaces with grained paintwork. Her furniture was of the same period too, or older. Her face brightened like the sun on seeing she had visitors.

“Mrs. Quackworth,” the children would say.

“They're spoilt. You’ll turn that girl into a proper trivet.”

The house smelled of cigarettes and boiled rabbit, and she always had a bottle of sherry on the go on the sideboard. Age made her more and more outspoken. We used to say we went to be insulted.

“What colour is that you're wearing? Grey? How drab! And what’s the matter with your hair? Are you going bald?”

“Your father says he’s going to give up smoking. I can’t see why. He’s not a smoker. One or two a day doesn’t count.” She considered herself a proper smoker: one or two packets a day.

One day she found him waiting for his pension in the Post Office. “What are you doing in here taking up a space?” she said to the amusement of the long queue. “Surely you don’t have any need for your pension, not you with all your money.”

She complained he had offered her a lift home “in case I had any heavy bottles to carry” she told us. “Anyone would think I was a drinker.”

She stayed active into her nineties, making the coal fire in the mornings, trudging to the supermarket for shopping and carrying home her heavy bottles. We were beginning to think she would outlive us all. When the time eventually came and her will was found there was a surprise in store. Although it was not worth anything like as much as she might have imagined, and a fifth of what it would fetch today, my brother and I were astonished to discover she had left us the house. For just a few weeks, the open fireplaces, grained paintwork, French windows, green shed, rockery and garden belonged to us. I swear if we had looked carefully enough, we could have found stray brambles still growing in the dark corners.

Some months later, my father bumped into Timmy’s parents shopping in town.

“We see Mrs. Ackworth’s house is sold at last,” they said. “The end of an era! Does anyone know what happened to her money?”

My father struggled to hold his tongue.

Sunday, 22 January 2017

The Restless Friend

From Great Heck and the Norfolk Broads to Southern Rhodesia: the contrasting lives of childhood friends.

High on the mantelpiece in the back room of the house where I grew up, were photographs of my mother and father taking turns to wear a captain’s hat at the wheel of a houseboat on the Norfolk Broads. My dad’s pipe is jauntily raked at an angle that would not have been out of place in someone commanding a much larger vessel. He puts on a show of self-importance while my mum looks relaxed and happy. How young and carefree they seem; from a time before I was born.

My dad remembered this post-war holiday fifty years later. They went with his school friend Freddy and wife Sylvia. My mum, Freddy and Sylvia went on ahead because Dad had to work the first Saturday. He took his suitcase in the firm’s van and was dropped off at Heck railway station, between Selby and Doncaster, where he took a direct train to Norwich. He remembered the splendid sight of Ely Cathedral in the evening sun. He was young, the war was over and he was off on holiday with his new wife and friends: for all of them the future was rosy.

You might be surprised to learn there was ever a direct train from Heck to Norwich, but during the war the tiny station at Great Heck gained unusual importance due to its proximity to No. 51 Heavy Bomber Squadron, R.A.F. Snaith, a short distance along a country lane between Heck and nearby Pollington. Also at Pollington were army barracks and one of the largest Women’s Land Army quarters in the country. Some 3,200 extra personnel were drafted into a village of 650. My dad’s train was a residual wartime service. He actually caught it on the very last Saturday it ran.

Great Heck has no railway station at all now. It disappeared around nineteen-sixty along with its neighbours at Temple Hirst, Balne and Moss. My dad once took me there in the nineteen-fifties to watch powerful Atlantic and Pacific locomotives race through non-stop on the East Coast Main Line between York and Doncaster. By then the station had already declined into obscurity and might never have been heard of again had it not been the site of the terrible Great Heck rail crash in February, 2001. Even that is often referred to as the Selby rail crash.

Pollington Airfield has also gone. A few derelict hangars remain but the runways and taxiways have all but crumbled and the site is used now by haulage and storage companies. For much of the nineteen-sixties and -seventies it was a popular off-road spot for learner drivers to make their first juddering attempts at starting, steering, stopping and changing gear.

Back in the photographs, it is Freddy’s cap they are wearing. On leaving school he had initially begun to train as a ship’s officer, but wartime on the ominous North Atlantic convoys had left him restless. He exchanged his sextant for the cricket team and a job in a railway office. The drudgery was too much. While my dad remained in his small Yorkshire town, Freddy left for the champagne air of colonial Southern Rhodesia, seeking excitement and adventure over caution and insularity. Sylvia followed soon after with their two young children. That is what wives did in those days whether or not they really wanted to.

They left in 1952 and lived very comfortably for a time. Whites in Rhodesia had servants, sizeable houses with pleasant gardens and swimming pools, and good health care and education. The climate was wonderful and it was one of the richest communities in the world. I don’t know whether Freddy ever came back. Online ships’ manifests only show Sylvia and the children spending five months in Yorkshire without Freddy in 1955, but the records are incomplete.

What I do remember is that each Christmas Freddy sent my dad a subscription to the Reader’s Digest. My dad thought it the affected urbanity of a smug high-flier and was irritated by the complacent, patronising content. But children have time to read such things: the features such as ‘Laughter the Best Medicine’, ‘Humour in Uniform’, ‘Life’s Like That’ and ‘Test Your Word Power’, the biographies and articles on technology and medicine, the condensed books. I still, for old time’s sake, go straight to the piles of back-issues in holiday cottages and waiting rooms. Thankfully my word power fairs better now. It is easy to see why it was once one of the highest-circulation periodicals in the world, despite all the junk mail that comes with it.

The gift subscription continued into the nineteen-sixties despite nothing ever being sent back in return, not even a Christmas card, as we did not know Freddy’s address. It may have been in Bulawayo. One year the subscription stopped. Perhaps he had decided not to bother any more. We gradually forgot about it. It was a long time before we heard what had happened.

Two decades later, Sylvia unexpectedly returned to England, alone and penniless. It transpired that Freddy, clever with money, had made a small fortune on the stock market, but had also developed an alcohol problem. Eventually he left and moved to Hong-Kong where he later died. Sylvia had remained in Rhodesia (by then Zimbabwe) until, forced by the economic and political situation there, she returned to Yorkshire. She had not been allowed to bring any money out of the country. She came back to be near her daughter, but her daughter died fairly soon afterwards. Sylvia spent the rest of her days in our small Yorkshire town on benefits in a bedsit, surrounded by second-hand furniture.

High on the mantelpiece in the back room of the house where I grew up, were photographs of my mother and father taking turns to wear a captain’s hat at the wheel of a houseboat on the Norfolk Broads. My dad’s pipe is jauntily raked at an angle that would not have been out of place in someone commanding a much larger vessel. He puts on a show of self-importance while my mum looks relaxed and happy. How young and carefree they seem; from a time before I was born.

My dad remembered this post-war holiday fifty years later. They went with his school friend Freddy and wife Sylvia. My mum, Freddy and Sylvia went on ahead because Dad had to work the first Saturday. He took his suitcase in the firm’s van and was dropped off at Heck railway station, between Selby and Doncaster, where he took a direct train to Norwich. He remembered the splendid sight of Ely Cathedral in the evening sun. He was young, the war was over and he was off on holiday with his new wife and friends: for all of them the future was rosy.

You might be surprised to learn there was ever a direct train from Heck to Norwich, but during the war the tiny station at Great Heck gained unusual importance due to its proximity to No. 51 Heavy Bomber Squadron, R.A.F. Snaith, a short distance along a country lane between Heck and nearby Pollington. Also at Pollington were army barracks and one of the largest Women’s Land Army quarters in the country. Some 3,200 extra personnel were drafted into a village of 650. My dad’s train was a residual wartime service. He actually caught it on the very last Saturday it ran.

Great Heck has no railway station at all now. It disappeared around nineteen-sixty along with its neighbours at Temple Hirst, Balne and Moss. My dad once took me there in the nineteen-fifties to watch powerful Atlantic and Pacific locomotives race through non-stop on the East Coast Main Line between York and Doncaster. By then the station had already declined into obscurity and might never have been heard of again had it not been the site of the terrible Great Heck rail crash in February, 2001. Even that is often referred to as the Selby rail crash.

Pollington Airfield has also gone. A few derelict hangars remain but the runways and taxiways have all but crumbled and the site is used now by haulage and storage companies. For much of the nineteen-sixties and -seventies it was a popular off-road spot for learner drivers to make their first juddering attempts at starting, steering, stopping and changing gear.

Back in the photographs, it is Freddy’s cap they are wearing. On leaving school he had initially begun to train as a ship’s officer, but wartime on the ominous North Atlantic convoys had left him restless. He exchanged his sextant for the cricket team and a job in a railway office. The drudgery was too much. While my dad remained in his small Yorkshire town, Freddy left for the champagne air of colonial Southern Rhodesia, seeking excitement and adventure over caution and insularity. Sylvia followed soon after with their two young children. That is what wives did in those days whether or not they really wanted to.

They left in 1952 and lived very comfortably for a time. Whites in Rhodesia had servants, sizeable houses with pleasant gardens and swimming pools, and good health care and education. The climate was wonderful and it was one of the richest communities in the world. I don’t know whether Freddy ever came back. Online ships’ manifests only show Sylvia and the children spending five months in Yorkshire without Freddy in 1955, but the records are incomplete.

What I do remember is that each Christmas Freddy sent my dad a subscription to the Reader’s Digest. My dad thought it the affected urbanity of a smug high-flier and was irritated by the complacent, patronising content. But children have time to read such things: the features such as ‘Laughter the Best Medicine’, ‘Humour in Uniform’, ‘Life’s Like That’ and ‘Test Your Word Power’, the biographies and articles on technology and medicine, the condensed books. I still, for old time’s sake, go straight to the piles of back-issues in holiday cottages and waiting rooms. Thankfully my word power fairs better now. It is easy to see why it was once one of the highest-circulation periodicals in the world, despite all the junk mail that comes with it.

The gift subscription continued into the nineteen-sixties despite nothing ever being sent back in return, not even a Christmas card, as we did not know Freddy’s address. It may have been in Bulawayo. One year the subscription stopped. Perhaps he had decided not to bother any more. We gradually forgot about it. It was a long time before we heard what had happened.

Two decades later, Sylvia unexpectedly returned to England, alone and penniless. It transpired that Freddy, clever with money, had made a small fortune on the stock market, but had also developed an alcohol problem. Eventually he left and moved to Hong-Kong where he later died. Sylvia had remained in Rhodesia (by then Zimbabwe) until, forced by the economic and political situation there, she returned to Yorkshire. She had not been allowed to bring any money out of the country. She came back to be near her daughter, but her daughter died fairly soon afterwards. Sylvia spent the rest of her days in our small Yorkshire town on benefits in a bedsit, surrounded by second-hand furniture.

Thursday, 6 October 2016

The Man With The Hebrew Bible

My father was always puzzled by a strange teenage memory. In 1937 he went with his parents to visit distant relatives at Boston in Lincolnshire. In one house, an elderly Jew was sitting at a high desk in skull cap and prayer shawl reading a Hebrew bible, his finger tracing the curious lettering right to left across the page. Who could this have been? My father was never aware of any Jewish relatives. He began to wonder whether he had imagined the whole thing. The truth, when it emerged, is like a tale from Dickens.

Years later, after his parents were gone and there was no one left to ask, the image kept returning to bother him like a recurring dream. He wished he had paid more attention, except you don’t when you are sixteen, or even when you are thirty-three or forty, his ages when his mother and father died. He struggled to reconstruct the event: the one-day railway excursion from Goole; meeting his mother’s cousin, Lucy Mann, who gave them dinner (i.e. lunch); climbing the three hundred and sixty five steps to the top of Boston Stump with his father (i.e. Boston St. Botolph, the tallest church tower in England). But the man with the Hebrew bible remained a mystery.

|

| The Hull Daily Mail, 1937 |

On the way home, my grandfather, amused by what they had seen, began to tease my grandmother about her distant relative. It was still unusual for people from a small Yorkshire town to encounter other religions or ethnicities, even for those who had seen service abroad during the First World War. It was cause enough for suspicion to be Roman Catholic, or sometimes Methodist. “Well, you kept quiet about that all these years, didn’t you!” he mocked. “I didn’t realise I’d married a Hebrew!”

My grandmother’s cousin, Lucy Mann, is also no mystery. The two cousins had spent the First World War together in service as shop assistants at Southport in Lancashire. They had a common bond: the childhood loss of a parent. Lucy’s father had died of heart disease in 1893 when she was two, and my grandmother’s mother of kidney disease in 1910 when she was fourteen. Lucy can be found in my grandparents’ wedding photographs in 1919. They remained in touch for the rest of their lives.

But who was the man with the Hebrew bible? My father gradually came round to thinking he could have been married to one of his mother’s aunts. We looked for clues in the snippets of family history I traced, but to no avail. None of the twelve aunts we found fitted the bill.

The truth came to light only after my father had died. It was the result of a set of events that would never occur today – like a nineteenth century Dickensian tale, convoluted as a Catherine Cookson saga.

It begins in the eighteen-fifties. My grandmother’s maternal family lived in a hamlet called Amber Hill in the Boston fens: an expanse of low lying farmland to the west of The Wash in South Lincolnshire. It is a bleak, wet landscape of isolated villages surrounded by field after field of crops. But for a network of deep drains and pumping stations originally powered by windmills, it would quickly turn back into marshland. You could imagine it as Holland; in fact one fen is actually named Holland Fen. Families were large, and the children went on to have large families themselves. Work on the land was hard and death came early and often.

My grandmother’s mother was one of at least twelve siblings. The two eldest, both girls, married the same man, the elder sister having died at the age of twenty. Between them they had fourteen children with the surname Sellars. One, Thomas Sellars, moved north to the town of Goole, then a booming port in Yorkshire. It promised a kinder life than on the land, with plentiful work on the docks, on the railway, and in the industries springing up around the town. Thomas found work as a coal porter, married and quickly had four children, but one died soon after birth, and then his wife died. It was May, 1906. Thomas was left alone with three children: Albert aged four, Beatrice, three, and Edmund, one.

Other siblings and cousins had moved to Goole too, including my grandmother’s parents. It would not have been entirely alien to them because, like the Boston fens, the land is flat and artificially drained. The families remained close, some lodging with or living next door to each other. They would have rallied round straight away to help Thomas with the children. A working man at that time could not have looked after them alone.

Soon, however, Thomas was on his own again. He remained in Goole, but the 1911 census shows him living alone in lodgings. Albert is back with Thomas’s parents in the Lincolnshire Fens. Edmund, the youngest child, had died in 1908. Beatrice is nowhere to be found. It seemed that she had disappeared from the records.

It is not unusual to have loose ends in family history research. Sometimes they are never resolved. My grandmother had at least fifty first cousins just on her mother’s side of the family, some of whom also seem untraceable.

Thomas died three years later in 1914. He is buried with his wife and children in a pair of forgotten and neglected plots in Goole cemetery. My grandmother would certainly have remembered her cousin Thomas and his family, being only a little older than his children.

This sad tale was all we could find for many years. We knew most of it before my father died. At that time it seemed to have absolutely no connection to the man with the Hebrew bible. It never occurred to either of us there might be one.

But the great thing about internet genealogy is that not only does it provide untold resources for tracing your family history, it also facilitates communication between distant relatives and others researching the same families. One day, out of the blue, I received a message from Beatrice’s grandson, actually my third cousin once removed, and the rest of the story fell into place. The man with the Hebrew bible acquired a name.

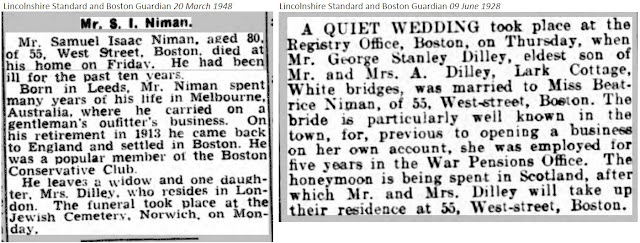

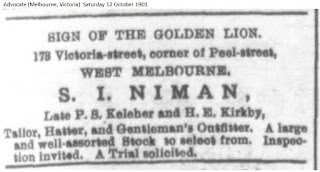

He was Samuel Isaac Niman, born in 1867 at Plock in central Poland. When he was two his family moved to England and settled in Leeds where he grew up. He trained as a tailor and at some point during the eighteen-nineties emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, to set up in business as a gentleman’s outfitter.

|

| The Melbourne Advocate, 1901 |

One of Thomas Sellers’ sisters, Mary Ann Sellars, had also moved to Melbourne. When, how and why remains unknown. She had been in domestic service in the 1891 census, but had then become another of those loose ends that disappeared from the family tree. It transpired that she had married Samuel Isaac Niman in Melbourne in 1900.

News of the death of Thomas’s wife would have been slow to reach them in 1906. One imagines letters sent back and forth by sea with an interval of six or seven weeks between dispatch and delivery. They would have touched upon the uncertain future of Thomas’s children. Exactly how the dialogue then developed one can only guess, but it seems the Nimans were unable to have children of their own and it was agreed they should take one of Thomas’s to live with them in Australia. In March, 1907, Mary Ann sailed from Melbourne, arriving in London in mid-May. Then on the 26th September she sailed back from Liverpool accompanied by five-year old Beatrice, and Beatrice Sellars became known as Beatrice Niman. One wonders what the little girl thought, sailing off to a new life on the other side of the world with an aunt she had known for just four months.

|

| The Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 1933 |

The Nimans remained in Melbourne for a further six years until, in July 1913, they returned to England and settled in Boston. Samuel started another business there, apparently with Mary Ann and Beatrice, eventually opening a ladies clothing shop at 55 West Street. They lived on the premises, which is where my father and his parents would have visited them in 1937. Beatrice by then was married with children of her own, but she still lived in Boston and may also have been present. We no longer know how well Mary Ann knew my grandmother or whether Beatrice remembered her. She would have remembered very little about her time in Goole with her own parents, but might have visited on returning from Melbourne in 1913 because her father, Thomas Sellars, was still alive. One can only wonder. The more you find about family history, the more questions you have.

So my father had not imagined the whole thing. The man with the Hebrew bible was real. He was Samuel Isaac Niman, the husband of one of my father’s mother’s cousins. Beatrice’s son remembered him as very religious. As a child he would sit on his knee at the high desk as he read the Hebrew bible.

Sadly, my father died six or seven years before I was able to tell him.

After Samuel's death, Mary Ann went to live with Beatrice and her family who had moved to Muswell Hill, London. She died there aged 84 in 1956.

Labels:

1930s,

biography,

dad,

family (childhood),

genealogy,

railways,

Rawcliffe/Goole/Howden,

religion

Sunday, 1 March 2015

A family tragedy

I thought very carefully before posting this. It’s here because, firstly, I

found it upsetting at the time having known some of those involved. Secondly, the story has warnings for us all as to what we are capable of when things become too much to bear. I have omitted details that might identify those concerned other than to people who already know.

* * *

Leaving home can be a testing rite of passage. This is true even in cocooned university or college environments where there are organised social activities and lots of others in the same boat. But it can be relentless when you’re on your own.

My first few months were particularly difficult and depressing, marooned in an unfamiliar city, struggling to understand the uncertainties of a new job where nearly everyone at work was older or with very different lives, and expected to begin a demanding, time-consuming correspondence course in a new and alien subject. There was also something strange about where I lived, a pervasive sense of shame hinted at in surreptitious glances, hushed whispers and neighbours watching behind twitching curtains as I entered and left the house. It was some months before I found out why, and some years before the truly dreadful story reached its terrible and tragic conclusion.

We had placed an advertisement in the Yorkshire Post, “Trainee accountant requires lodgings in Leeds, Monday to Friday, bed breakfast and evening meal,” and quickly received a reply from a widow with a vacant room. She lived in King George Avenue, a couple of miles North of the city centre, where Chapeltown Road and Harehills Lane merge to become Harrogate Road. It looked comfortable when we went to look, and so one Sunday afternoon in September, 1968, my dad took me in the car and left me there.

Although King George Avenue lies at the end of the notorious Chapeltown Road, by the time you get there you are in Chapel Allerton, a green and pleasant suburb where substantial family homes nest in well-established, tree-filled gardens. It looks much the same today, an agreeable place to live. Near the entrance to the avenue, twin stone arches with wrought iron gates mark the gatehouse of Chapel Allerton hospital, then the ‘Artificial Limb Centre’. The weathered remnants of its sign are still on the wall next to the right hand arch today, almost legible in the Google Street View image of June 2008. Just into the avenue, the leafy Gledhow Park Drive leads off on the right. My landlady never tired of telling me how, not so many years before, they had become accustomed to seeing the young actress Diana Rigg pass by, whose parents lived in the Drive.

My landlady lived with her youngest daughter Helen, a lovely, gentle, long-haired Jewish girl some five or six years years older than me. Three older children had married and left home. There was also another lodger in the house, a girl who had a room upstairs, but I hardly ever saw any of them. My own room was downstairs where the house had been extended to make it wider. There was a door at one end out to the hall and front door, and a door at the other end through which the landlady brought my breakfast and evening meal from the kitchen. There was a bed, a table and dining chair, an armchair and a built in cubicle containing a washbasin and toilet, and that was it. I came in from work, had my meal, and was then left undisturbed until next morning.

It sounds ideally suited to getting on with the accountancy correspondence course I was supposed to be working through, and so it should have been, but I couldn’t apply myself to it at all. After leaving for work before 8.00 a.m. and not getting back until 6.30 p.m. it was hard to study with much enthusiasm (the office hours were 8.45 a.m. to 5.30 p.m., with an hour and a quarter for lunch, making 37½ hours per week). I tended to fall into an exhausted torpor worsened by boredom and loneliness. At £6 per week, the rent was more than I earned, so I had to be subsidised by my parents and couldn’t afford to go out. I can’t emphasise enough how much I looked forward to the 17.35 train home every Friday, and how much I dreaded the early Monday morning train back.

After some weeks, when they had got to know me a little better, I was invited to watch television with the landlady and her daughter at agreed times, such as ‘Top of the Pops’ on Thursdays. They asked me about my family and talked a little about theirs, and I began to feel more at home and started to like them, but the feeling remained that they had something to hide. They spoke in Yiddish whispers as if not wanting “the goyim” to hear their “tsuris” (the gentiles to know their troubles), and the evening meal became increasingly slapdash and hastily prepared. From meat, potato and a vegetable at first, it was now beans or eggs on toast. One night I went back to a tin of Heinz spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce for my tea. One week I got tinned meals every night. I might have starved but for being able to get something more substantial during the day – a least a good sandwich or a proper pub lunch on expenses when working out of the office.

I began to look for somewhere else to live, and one of the seniors at work put me in touch with an elderly couple at Kirkstall who were looking for a new lodger. I arranged to go there from the beginning of the new year and was surprised by my parents’ reaction: they seemed keen for me to move as soon as possible. After I’d left King George Avenue they told me why.

They had noticed a report in the newspaper that a thirty-three year old man of King George Avenue, an unemployed company director with the same surname as my landlady, had been found guilty of incitement to murder. It transpired he was in fact my landlady’s eldest son and his awful story had been unfolding for over a year.

The previous year, after six years of marriage, his wife had divorced him and gained custody of their only child, a son then aged four. The divorce mainly seems to have been due to his obsessive and unstable personality. He had been worried about the health of his father, who had died, and about his business where he worked excessively long hours, often seven days a week. There was also a mutual dislike between him and his father-in-law. After the divorce he became gripped with hatred for his ex-wife and her parents, and the man she later married, and made disturbing and graphically violent threats towards them: his ex-wife was a model and he wanted acid thrown in her face to ruin her looks; he wanted his father-in-law’s tongue torn out so he would never speak again. His obsession culminated in a breakdown and treatment as an in-patient at a psychiatric hospital.

In December, after leaving hospital, he snatched his son from outside his ex-wife’s home and attempted to take him to Eire, presumably because this would have been beyond the jurisdiction of the custody order, but was apprehended in a taxi in Northern Ireland, three miles from the border, and jailed for two months for contempt of court.

While in prison, he attempted to find someone to murder his ex-wife for money. He put a proposal to a man he thought could arrange it, but the man was actually an undercover police officer. When after his release he tried to put the plan into operation, he was arrested again. He was convicted of incitement to murder by attempting to employ two men he thought were London gangsters to kill his ex-wife and her parents, and her male friend, and given a further three-year prison sentence. It would have been longer had the judge not taken into account his mental state and medical opinion that he was no longer dangerous.

My parents had decided it best not to mention any of this while I was still at King George Avenue, and as I rarely read the newspaper in those days I had missed it completely. The week I got tinned things every night for tea was the week of the trial. There is little wonder my landlady and daughter were so preoccupied.

Four years later, long after I had moved on, there was a most terrible and tragic sequel to this story. After serving his sentence, my ex-landlady’s son enrolled as a mature student in sociology at Leeds University. Now, I have experience of this and can tell you that becoming a mature student is not something you should undertake without being mentally and emotionally robust enough to handle it. Mature students have high and sometimes unrealistic expectations of themselves. They take their studies very seriously. They stretch the limits of their mental powers. But students also have long free hours for deep thought and reflection – that’s what being a student is all about. If you have any hidden demons they will jump out and come for you. I have seen this so many times in different forms and in different degrees of severity. The case of my ex-landlady’s son was the worst imaginable

One Sunday at the end of January, he and his son spent the day together under access conditions which allowed contact once per month in the presence of a chaperone - severely restricted in light of previous events. They had played darts and football and then driven to a golf club to the North of Leeds at Shadwell. They had all enjoyed the day tremendously. My ex-landlady’s son then tricked the chaperone into leaving them briefly by telling him he was urgently needed on the telephone inside the golf club, and drove off with his son. At first it was thought to be a further abduction attempt, but it was far worse. He parked nearby in a quiet country lane, shot his son three times, and then turned the gun on himself. Their bodies and a shotgun were found in the car around tea time. His last wish was to be laid to rest with his son but perhaps understandably he was buried alone. He was thirty-eight.

Police later found he had left a tape recording at home speaking of his anguish at being allowed access to his son only once per month. The inquests returned a verdicts of murder and suicide, with indications that the tragedy had been carefully planned. This was long after I had moved on, but when I read about it I thought of the house in King George Avenue, and my landlady, and her daughter, and her son’s poor ex-wife, and could not begin to imagine what they must be going through.

POSTSCRIPT

Around the time I left King George Avenue I remembered an odd incident which I have always wondered whether it had any bearing on where I was staying. On my very first morning at work, I caught the bus along Chapeltown Road into town, and was walking along the Headrow a little unsure of my bearings when a voice behind asked “On our way to work then are we?” I was surprised to see someone I knew vaguely from my home town wearing a police cadet uniform. I could not remember his name and didn’t get chance to ask because the whole of our fairly brief conversation was taken up by his questions – where was I working, when had I started, where was I living, how long had I been there, how had I found it, and so on. I’ve often wondered since whether it was just coincidence or was I being checked out. I did remember his name later but never saw him again.

* * *

Leaving home can be a testing rite of passage. This is true even in cocooned university or college environments where there are organised social activities and lots of others in the same boat. But it can be relentless when you’re on your own.

My first few months were particularly difficult and depressing, marooned in an unfamiliar city, struggling to understand the uncertainties of a new job where nearly everyone at work was older or with very different lives, and expected to begin a demanding, time-consuming correspondence course in a new and alien subject. There was also something strange about where I lived, a pervasive sense of shame hinted at in surreptitious glances, hushed whispers and neighbours watching behind twitching curtains as I entered and left the house. It was some months before I found out why, and some years before the truly dreadful story reached its terrible and tragic conclusion.

We had placed an advertisement in the Yorkshire Post, “Trainee accountant requires lodgings in Leeds, Monday to Friday, bed breakfast and evening meal,” and quickly received a reply from a widow with a vacant room. She lived in King George Avenue, a couple of miles North of the city centre, where Chapeltown Road and Harehills Lane merge to become Harrogate Road. It looked comfortable when we went to look, and so one Sunday afternoon in September, 1968, my dad took me in the car and left me there.

Although King George Avenue lies at the end of the notorious Chapeltown Road, by the time you get there you are in Chapel Allerton, a green and pleasant suburb where substantial family homes nest in well-established, tree-filled gardens. It looks much the same today, an agreeable place to live. Near the entrance to the avenue, twin stone arches with wrought iron gates mark the gatehouse of Chapel Allerton hospital, then the ‘Artificial Limb Centre’. The weathered remnants of its sign are still on the wall next to the right hand arch today, almost legible in the Google Street View image of June 2008. Just into the avenue, the leafy Gledhow Park Drive leads off on the right. My landlady never tired of telling me how, not so many years before, they had become accustomed to seeing the young actress Diana Rigg pass by, whose parents lived in the Drive.

My landlady lived with her youngest daughter Helen, a lovely, gentle, long-haired Jewish girl some five or six years years older than me. Three older children had married and left home. There was also another lodger in the house, a girl who had a room upstairs, but I hardly ever saw any of them. My own room was downstairs where the house had been extended to make it wider. There was a door at one end out to the hall and front door, and a door at the other end through which the landlady brought my breakfast and evening meal from the kitchen. There was a bed, a table and dining chair, an armchair and a built in cubicle containing a washbasin and toilet, and that was it. I came in from work, had my meal, and was then left undisturbed until next morning.

It sounds ideally suited to getting on with the accountancy correspondence course I was supposed to be working through, and so it should have been, but I couldn’t apply myself to it at all. After leaving for work before 8.00 a.m. and not getting back until 6.30 p.m. it was hard to study with much enthusiasm (the office hours were 8.45 a.m. to 5.30 p.m., with an hour and a quarter for lunch, making 37½ hours per week). I tended to fall into an exhausted torpor worsened by boredom and loneliness. At £6 per week, the rent was more than I earned, so I had to be subsidised by my parents and couldn’t afford to go out. I can’t emphasise enough how much I looked forward to the 17.35 train home every Friday, and how much I dreaded the early Monday morning train back.

After some weeks, when they had got to know me a little better, I was invited to watch television with the landlady and her daughter at agreed times, such as ‘Top of the Pops’ on Thursdays. They asked me about my family and talked a little about theirs, and I began to feel more at home and started to like them, but the feeling remained that they had something to hide. They spoke in Yiddish whispers as if not wanting “the goyim” to hear their “tsuris” (the gentiles to know their troubles), and the evening meal became increasingly slapdash and hastily prepared. From meat, potato and a vegetable at first, it was now beans or eggs on toast. One night I went back to a tin of Heinz spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce for my tea. One week I got tinned meals every night. I might have starved but for being able to get something more substantial during the day – a least a good sandwich or a proper pub lunch on expenses when working out of the office.

I began to look for somewhere else to live, and one of the seniors at work put me in touch with an elderly couple at Kirkstall who were looking for a new lodger. I arranged to go there from the beginning of the new year and was surprised by my parents’ reaction: they seemed keen for me to move as soon as possible. After I’d left King George Avenue they told me why.