Sure by Tummel and Loch Rannoch and Lochaber I will goAs step I wi’ my cromack to the Isles.

Said to be one of the last remaining wildernesses in Europe, it is a bleak stretch of blanket bog, lochans and rocky outcrops to the West of Loch Rannoch in Scotland. The West Highland Railway crosses it on the way to Fort William and Mallaig, over peaty terrain so wet that the Victorian engineers had to float the track on a mattress of brushwood, earth and ashes to stop it sinking into the bog.

Other than by train, the only way to Rannoch Station is by thirty miles of narrow B road meandering along the northern shore of Loch Rannoch from Pitlochry or Aberfeldy. Neville, Kev, and I, had driven there the previous Easter to sit cheerfully swigging our pints outside the Moor of Rannoch Hotel in the warm April sunshine. We watched a goods train rumble slowly north across the Rannoch Viaduct.

But it was the enigmatic wording of the signpost that caught our attention:

What a walk that must be!

The following year, Easter was a full two weeks earlier and the seasons over two weeks later. A letter from Major J. D. Rennie of the Moor of Rannoch Hotel, Rannoch Station, Perthshire, replying to our enquiry, said that, yes, we could leave our car at the hotel for a few days provided we left the keys so they could move it if necessary. However, he still seemed surprised when we turned up in the snow. We camped that night beside the nearby lochan. By morning, the pan of water left outside had frozen solid. At least it was too cold and early in the year for the midges.

It would not be beyond endurance to walk the thirty miles from Rannoch to Fort William in a day, but it seemed ideal for a first attempt at backpacking. We loaded our aluminium framed rucksacks, left the car keys with the Major, and set off northwards beside the railway track. And apart from the railway track, there was little else to see for the first ten miles but vast, uninhabited empty moorland. Being Easter Sunday, there weren’t even any passing trains to disturb the isolation. Remote, beautiful, desolate! We saw no one else all day.

The land gradually rises to a summit beyond Corrour, the next station on the line. It was shrouded in mist. The station, since made popular by the film Trainspotting, is now busy with walkers and mountain bikers, and Corrour Station House is a popular restaurant and guest house, but in 1975 there was very little there. We passed without much pause heading for our first overnight camp at Loch Treig. It could not come soon enough. My feet were a mess. Idiotic to attempt such a walk in new boots.

We covered about eight miles on day three, struggling with our heavy rucksacks across difficult ground. Continuing west, the river becomes angrier and whiter, the wide banks giving way to a steep-sided valley sparsely lined with silver birch. It then becomes still again, with banks of stony mudflats, and the country opens up into wide, browny heath and moorland. But as you approach the once fine house of Luibeilt, now a lonely ruin, you have to ford the river.

We knew the technique. Trouser legs up, socks off, boots back on, wade across with caution, and most importantly, do not lose your footing. The river was not particularly high and should have been trouble free, but it wasn’t. At least I was not the one to slip and fall in, losing the capacity either to give or refuse consent to be photographed ignominiously paddling out.

While drying out, two countryside rangers waded across, the only others we saw on the whole walk. As you would expect, they made it look easy. We chatted with them for the next few miles. They asked whether we had been staying at Luibeilt. It was listed by something called The Mountain Bothies Association as a place of overnight refuge. It sounded good for the future and I joined fairly soon afterwards.

The rangers sped ahead and disappeared into the distance as we approached the east-west watershed where the water flowing east towards Loch Treig along the Abhainn Rath becomes the water flowing west to Fort William down the Water of Nevis. Several valleys converge here and it was not immediately obvious which one to take, but a bit of map and compass work put us safely in the right direction. No G.P.S. in those days. The slight uncertainty makes for much more fun.

We camped again surrounded by the mountains of the Nevis valley: Aonach Beag, An Garbhanach, and Binnein Beag where deer came down the slopes in the night and made their way back up the next morning, avoiding the worst of the snow that sprinkled the tent.

We were soon up and on our way again, descending through the steep gorge of Glen Nevis to the end of the road at the base of Ben Nevis, where the misspelt signpost indicated whence we came.*

But that was not the end. We still had to face another five gruelling miles along the narrow road to the Glen Nevis camp site.

We allowed ourselves the next day off, and early the day after that packed up and hiked into Fort William for the train back to the car. It was a little further to walk than now. The original Fort William station alongside Loch Linnhe, with its turreted entrance on the main street, was still in use. It closed and moved east to the present site two months later.

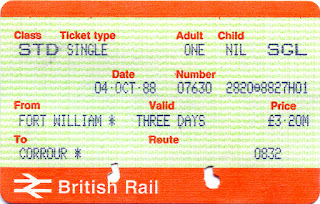

I did that walk twice again with different friends, once in 1978 and again in 1988, both times by taking the train to Corrour from the new station at Fort William, thus omitting the wearisome Rannoch to Corrour stretch. Sensibly, we also left one of our cars at the end of the Nevis road making it just a fifteen-mile walk – a good day out. On both occasions we were the only ones to leave the train at the deserted Corrour halt, to the incomprehension of the other passengers who looked down (both physically and metaphorically) from the carriage windows with bemusement at our cagoules, walking boots and daysacks.

I doubt it would be such a solitary walk now that most days the train deposits scores of walkers and mountain bikers at Corrour to follow numerous routes around the moor. The station is used by over twelve thousand passengers per year, an average of over thirty a day, but probably many times more in summer and fewer in winter. “Like a Wallace Arnold bus trip,” my dad would have said. It is a privilege to be able to say I was there in quieter times, nearly fifty years ago, but it would be wonderful to go again.

Take it away, Andy:

Notes

* The same sign and post are still at Glen Nevis (or were until relatively recently). The sign is considerably weathered, but the spelling of Corrour has been corrected and further signs to Spean Bridge, Corrour Station and Kinlochleven affixed in both Scots Gaelic and English.

On one of the later occasions there were signs of construction taking place at Luibeilt, but I see from more recent accounts that it is now a ruin without roof, woodwork or some walls.

I would not be so confident drinking water from mountain streams now.