|

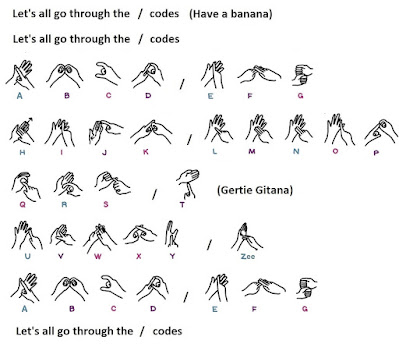

Village Dance Class, 1930s.

My mother (top, 3rd from right) is one of four “cousins” in the picture.

She would have been 100 years old today. |

“It was a lovely place to grow up”, said Aunty Olga the last time we spoke. “The best anyone could want”. She talked of a High Street with no motor vehicles to stop you playing in the road, all the relations living nearby, and how everyone knew each other and were friends. There were shops with all you could want, and clubs and groups and things to do. The buses ran late so you could get back from the pictures in town. “Not like now”.

“Aunty” Olga. We called them all “Aunty” or “Uncle", or if they were the same age as us “cousins”, no matter whether they were really great aunts, great uncles, second cousins, half-cousins, cousins once removed, or some other combination. It was simpler. There were loads of them. “Your mother was more of a sister than a cousin to me”, Aunty Olga said.

I caught it right at the end, and don’t doubt her. I fetched milk from the farm dairy and talked to the pig in the butcher’s sty. I bought pop from the sweet shop, chips from the fish shop, rolls of gun caps for my cowboy pistol and foreign stamps for my collection near The Green. I marvelled at the old village water pump near the church and walked on my own the three-quarters of a mile along the river bank to my aunt’s smallholding at the ferry houses. I knew the local names that appeared on few maps: Gander’ill; Cock’orner; Cuckoo Park.

A walk down the High Street with my grandma meant talking to everyone we passed.

“Who was that?”

“My cousin.”

“And who was that?”

“He’s my cousin too.”

“How many cousins have you got?”

I’d wish I’d not asked.

“Well, there was Aunty Bina who had Blanche, Tom, Gladys, Lena, Olga, Fred, Ena, Dolly, Albert and Jack. She brought up our Jean as well, although her mother was really Ena. They had fish and chip shops all over.”

“Then there was Aunty Annie who married Uncle George, and had Mary, Fred, and Bessie.” She pointed to ‘M, F, and B’, scratched long ago into the bricks of number 88 (still visible today).

“Do you mean Aunty Mary?” I asked. Aunty Mary had the prettiest face I’d ever seen.

If Grandma was in the mood, she would go on to list the millions of children of uncles Fred, Bill and Horner, who had moved away to run a paper mill in Lancashire.

All were prefixed “our”: our Fred, our Bessie, and our Mary. Aunty Olga’s children were our Linda, our Sandra, and our Gillian. It distinguished them from Aunts and Uncles who were not relatives at all, such as Aunty Annie ’agyard (3 syllables). What funny names some had.

And that was only one of Grandma’s sides. The other was worse.

Even more confusing, my mother’s Great Aunty Bina was married to my dad’s grandpa’s cousin, which meant I was doubly related to Blanche, Tom, Gladys, and the rest.

I heard it so often I could recite it to my wife decades later: “Blanche, Gladys, Ena, Lena, Gina, Dolly, Molly, Mary, Bessie, Ella, Olga, Linda...”

“They sound like a herd of Uncle Bill’s cows,” she said.

Uncle Bill (don’t ask), was from across the river and had married into the family. He said that if the Blue Line bus had not started running through the village, they would have all been imbeciles because of inbreeding.

I went less and less as I grew into my teens, not realising it was coming to an end. It would never be the same again.