Another blogger (the multi-talented Yorkshire Pudding) posted about a beer mat he had designed for his daughter’s recent wedding. One commentator said her grandfather collected beer mats but she thought that “In England they don’t seem much of a feature.”

Well, Ursula, my group of friends collected them in our youth. I stuck mine on the wall of a room above the garage at my parents’ house. This is part of a black and white photograph taken in 1970:

Most are English but a few came from exchange trips to Belgium (where you could drink alcohol in cafés at sixteen). I can make out the following:

Belgian mats: Maes Pils, Cristal Alken, Pela, Siréne, Barze, juni vakantie maand, Orval, Gereons Kölsch, Kess Kölsch, Diekirk, Falken, Sester. I can’t make out the mat with the bell which appears across the top and several times lower down, nor the one with the black horse – it isn’t “Black Horse”.

English mats: HB (Hull Brewery), Brewmaster Export Pale Ale, Whitbread Tankard, Whitbread Forest Brown, Tetley, Flowers Keg Bitter, Bass Export Ale, Have a mild Van Dyck cigar with your Bass Blue Triangle, Brown Peter for Strength, Strongbow Cider, Woodpecker Cider, Barnsley Bitter, Alpine Lager, Whitbread Trophy Bitter, Whitbread Pale Ale, Calypso, Youngers Tartan, Duttons Pale.

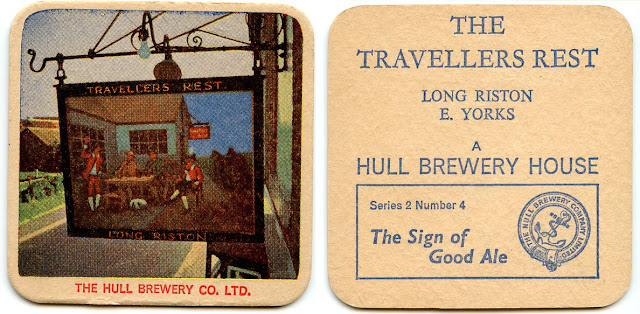

And among my box of colour slides and black and white negatives were these slightly later beer mats. Commodore Pudding will surely be delighted to see the one from The Travellers Rest at Long Riston, just three miles from his childhood village. Can’t remember my visit to the establishment though.

Google Analytics

Tuesday 27 August 2019

Monday 26 August 2019

Teenage Mums

| Fairy Liquid ads 1960s (3 in sequence) |

Thirteen! I kid you not. In later life she couldn’t believe it herself. Nowadays, it’s more likely she would have a real one.

It reminds me of a joke about the much-parodied detergent ad:

now hands that do dishes can feel as soft as your face

with mild green Fairy Liquid

Mummy, why are your hands so soft?

Because I’m only fifteen.

Labels:

1940s,

1960s,

film television radio,

mum,

toys and models

Sunday 18 August 2019

Plums

The biggest, tastiest, juiciest plums we’ve had in over twenty-five years here. They seem to have thinned themselves out naturally during the earlier hot, dry weather and then swelled to perfection in the recent rain. At last, something to match the produce from all those gardener-bloggers who don’t live at 750 feet in the north of England.

Gardening for me now has become a case of simply keeping things under control, hoping to benefit from the fresh air and exercise. I enjoy it but we don’t have anything that would pull in the crowds at the village open day.

It started when I was little and wanted to “plant some seeds”. Dad dug up a thin line of lawn along the front of the shed and sowed some Virginian Stock – his mother used to like them he said. Soon I was studying flower catalogues, taking geranium and hydrangea cuttings, transplanting clumps of oriental poppies begged from relatives and spending my pocket money on anemone bulbs and sweet william seedlings at the local gardening shop. I kept quiet about it at school, though.

I surrounded my little patch of garden with a miniature picket fence made from the wooden lollipop sticks that littered the streets (three sticks as uprights and four or five alternately woven in-out and out-in). I grew lettuces from seeds and tried to sell them door-to-door from my bicycle saddle bag – almost too embarrassing to remember. I helped myself to some rhubarb rhizomes from an unkept allotment down by the railway but Mum made me take it back: the first time I heard the word “pilfering”.

Nowadays, I try to put on a decent display in the front garden, still sometimes with a few Virginian Stocks and those daisy things my dad always misnamed “mesantheambriums”. At the back we have various beans, Sungold orange cherry tomatoes, courgette, strawberries, raspberries, apples, pears and plums. Potatoes do well when I make the effort, but other things like cucumbers, beetroot, carrot, cabbage and cauliflower have suffered so often from mildew, grubs or caterpillars I rarely bother. And we must have some of the most health-conscious sparrows in the country; they peck peas and lettuce to shreds.

We also keep a sizeable wild patch under the trees for the hedgehogs who visit our feeding station. We captured this on an infra-red video camera last year:

Things are always a month behind everyone else here. This year has been particularly disappointing: we are still waiting for our first tomatoes. At least we can enjoy the plums.

You might also like: Help ... my courgette looks like a duck!

Friday 9 August 2019

From Ferrybridge to Finland

|

| Demolition of Ferrybridge Tower 6 (click to play video) |

Those huge cloud factories, the eight enormous cooling towers of Ferrybridge C Power Station, have stood beside the A1 in Yorkshire for over fifty years (the power station itself has existed one form or another for over ninety), but not for much longer. One tower was demolished on July 28th, four more will go in October and all will be gone by 2021. The site has become a multifuel power generating plant burning waste and biomass, and using all the steam it generates.

Perhaps it’s for the best. In its heyday, Ferrybridge was one of the worst contributors to Scandinavian acid rain, which in 1993 memorably led the Norwegian environment minister Thorbjoern Berntsen to call his British counterpart, John Selwyn Gummer, the biggest “dritsekk” he had met in his life. Even so, I will miss its majestic scale.

I’ve contemplated the towers from miles away: from the top of the Wolds at South Cave near Beverley, from the top of the Pennines at High Flats near Huddersfield and from vantage points in the low lying Humberhead Levels. They have presided over my journeys to and from Leeds by train, bus and car after I left school, and welcomed me back to my part of Yorkshire when I’ve lived away. I have seen them from the air when flying from Scotland where I once lived to give a talk at a London conference, and from a flight to Helsinki. That’s my best memory.

It was in December, 1991, when I was with a Nottingham software company. I set off for the airport at Birmingham in the dark, in fog so thick I had to drive at walking pace with the window open just to be able to make out the white line in the middle of the road. The motorway wasn’t much better but I got there just in time, still in a gloomy blanket of fog.

I had a window seat but it was some time before things on the ground started to become visible. I could see what seemed to be moorland and dry stone walls, probably Derbyshire and South Yorkshire. Then suddenly we were out of it and over three enormous power stations in a straight line, and an island in a river with a familiar hook-shaped bend: unmistakeably Ferrybridge, Eggborough, Drax and the town of Goole laid out like a street plan. And there: a certain crossroads I knew so well. I was looking down on my dad’s house. He would be in his kitchen getting breakfast, absolutely oblivious to me peering down from an aeroplane two or three miles above.

Then, in next to no time we were over the Humber and flying past Hull with Hornsea Mere and the Yorkshire coast curving North to Flamborough just like on the map, and out over the North Sea to Copenhagen, and I realised I’d missed my complimentary whisky.

Oh my, Helsinki is cold in December. They have to run their car engines at least ten minutes with the heat full up the windscreen and lots of vigorous scraping before they can set off. I walked to the clients from the dingy hotel in the snow trying consciously not to breath in too much of the cold. Everyone had thick woolly mitts, hats and scarves in the brightest colours.

Back at the hotel there was evening entertainment from a lookalike John Shuttleworth keyboard and drums combo which I tried to ignore as I ate my tea. A forty-something woman asked me to dance. She said it was bad manners in Finland to refuse a woman who asks a man to dance. I said I was working and she said so was she. I made my excuses and left. I went to my room and locked the door. In the early hours I was awoken by a fight outside in the corridor. Dritsekks! Paska potkuts!

If you have to go to Helsinki, don’t go in December.

Update 13th October, 2019

Four more towers demolished today:https://www.itv.com/news/2019-10-13/power-station-towers-demolished-in-milestone-for-energy-industry/

https://twitter.com/AmyMurphyPA/status/1183342570769997826

Apparently the three remaining towers are to be retained for the time being in case they are needed for a new gas fired generator.

Labels:

1970s,

1980s,

1990s,

dad,

holidays and excursions,

Rawcliffe/Goole/Howden

Saturday 3 August 2019

Petrol Rationing

Could a no-deal Brexit lead to fuel rationing? There’s not much talk of it as yet but the Government would be negligent not to have plans in place.

In a recent post about petrol cans, I mentioned the 1973-74 oil crisis when rationing came close. Revisiting it again in archive newspapers reminded me what a comical tale of widespread selfishness and bureaucratic ineptitude it was. An indication of things to come, perhaps (~1400 words).

Here are some of the pages from my 1973 motor fuel ration book. Page 2 tells you to keep it safe. As you can see, I did.

According to most accounts now, the problems began in October 1973 when Arab oil exporters embargoed countries that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War. But you could see it coming months before then. The Government denied any possibility of a crisis as early as July: a sure sign one was on the way.

In early August, they sent out ration books to Post Offices. They said it was “only a precaution”, and even at the end of October, Trade and Industry Secretary Peter Walker was still assuring us there was no need for concern. We had stocks for another 79 days, with 30 more on the way in tankers on the ocean. By then, no one believed it and there was an outbreak of ‘fill-up fever’. We began to keep our tanks full to the brim, with extra in cans for emergencies. This made things worse. Petrol stations began to limit how much you could buy so as not to run out.

Come mid-November, Peter Walker was wagging his finger saying we had to conserve fuel by driving at no more than 50 m.p.h. and staying home on Sundays. Supplies to retailers were cut by 10% and the sale of petrol in cans was banned. But it was hard to keep to a dutiful 50 while bastards in Jags were whizzing past at 80, and we just filled our cans by surreptitiously siphoning from our vehicle tanks in private.

It was, in any case, illegal to store more than four gallons at home. Even then it had to be in the correct containers (such as my Paddy Hopkirk can pictured in the earlier post). Some thought they could ignore these rules. In Banbury, a taxi driver was fined £150 for storing 30 gallons in five-gallon drums in a garage, in Hinckley another man was fined £50 for having 90 gallons in a shed, and in Coventry an engineering rep. who drove 32,000 miles a year was fined £110 for hoarding 148 gallons. They must have spent hours siphoning it through rubber tubing. Some were even found to be storing petrol in cellars and attics, which, fire chiefs correctly warned, was extremely dangerous and could be ignited by a single spark. Simply switching on a light could result in a massive explosion.

On Monday 26th November, the Government announced that petrol coupons would be distributed to motorists from Thursday of that week, again, of course, “only as a precaution”. Coupons were to be issued at Post Offices on different days according to the initial letter of your surname, beginning with A and B on Thursday 29th November.

Postmasters complained. It was one of their busiest days of the year when pensioners collected their Christmas bonuses. Queues spilled out into the streets, swelled by motorists trying to renew their tax discs before the end of the month as they were needed to claim coupons and those that expired on the 30th November would not be accepted after that date despite normally being allowed fourteen days’ grace.

Coupons were then available progressively until names beginning W-Z collected them on the 12th December. Businesses then followed a similar rota. It does not seem to have been made clear what happened if you went late or on a wrong day; I suspect you got your coupons anyway. There were warnings from Scottish postmasters of potential chaos on ‘M’ day, December 6th, because nearly everyone’s name there began with M or Mc. Extra ‘M’ days were allocated in Lewis, Harris, Barra, and North and South Uist.

The coupons were actually left over from the 1967 Arab-Israeli War when they had been printed “as a precaution” but not needed, which was just as well because that war had taken place in June and the coupons were still being printed in December. At least it meant they were ready in good time for 1973.

To claim your coupons, you had to show your vehicle log book and current road tax disc. Motorists in Sheffield were among the first to be booked by traffic wardens for not displaying a tax disc while collecting their coupons.

Your log book was stamped to show your coupons had been issued. It was said some people were getting extra coupons illicitly by claiming to have lost their logbooks and obtaining replacements. It was left to motorists to enter the vehicle registration number on the front of the ration book. Books were therefore not necessarily tied to the vehicle for which they were issued, leading to fears of a black market.

Ration books contained six month’s worth of coupons. Everyone got a basic allowance depending on the size of their engine, so my 848cc Morris Mini (the blue one in the blog banner) fell into the ‘not exceeding 1100cc’ category, allowed four N units and two L units per month. The bigger the engine the more you got, the other categories being 1101-1500cc (they got 6N+2L or 4N+2L on alternate months), 1501-2200cc (7N+3L per month) and 2201cc plus (7N+4L or 7N+3L)*. Motor cycles got less, and buses and lorries more. Essential vehicles and drivers with special priority (doctors, nurses, vets, ministers of religion, welfare workers and some disabled people) could claim extra, and you could apply for a supplementary allowance in cases of severe domestic hardship (e.g. for getting to and from work where there was no public transport).

This all sounds very carefully thought out and precise, except that some Post Offices ran out of some categories of ration books and the Government would not say how many gallons each N and L unit might allow you to buy before rationing actually came in. You could make a guess based on the 1956-57 Suez crisis when motorists had a basic allowance for around 200 miles per month, but by 1973 the number of private cars on the road had more than tripled to 13.5 million so it could have been less.

While all this was going on, the miners and electricity workers had begun an overtime ban and the miners then went on strike for a 16.5% pay rise. Prime Minister Edward Heath announced a State of Emergency and the 50 m.p.h. speed limit was made compulsory from the 8th December, with motorists fined for exceeding it. Reduced street lighting brought an increase in petrol theft by siphoning, so we all had to buy locking petrol caps (they were not standard fittings then). Mine is still in a cupboard in the garage. Television broadcasts went off at 10.30 p.m. and the use of electricity for floodlighting and advertising was banned. We were urged to switch off lights and turn down the heating at home, and papers subsequently released under the 30-year rule reveal that the Government even considered making it illegal to heat more than one room. They would have needed officious A.R.P.-like wardens knocking on doors to check your room temperatures. Power cut rotas were drawn up as in the miners’ strike two years earlier and published in regional newspapers, but never implemented. However, from the 1st January 1974, most businesses were only allowed to use electricity on three days per week. It lasted until the 7th March.

I suffered no great hardship myself. At the time I was a mature student for a few futile months at Teacher Training College. I drove in and out of college each day, and further afield on teaching practice, days out walking in the dales and home to my parents at weekends, and was never short of petrol. Rationing was never implemented and my spare can remained full for at least a couple of years. It turned out to be a good investment because four-star doubled in price to around 75p per gallon (16½p per litre) between 1973 and 1975.

In the end, it was indeed only a precaution, but there was real irony to the 1973 Christmas Number One: So here it is Merry Christmas, everybody’s having fun.

* I think these coupon quantities are correct.

In a recent post about petrol cans, I mentioned the 1973-74 oil crisis when rationing came close. Revisiting it again in archive newspapers reminded me what a comical tale of widespread selfishness and bureaucratic ineptitude it was. An indication of things to come, perhaps (~1400 words).

Here are some of the pages from my 1973 motor fuel ration book. Page 2 tells you to keep it safe. As you can see, I did.

According to most accounts now, the problems began in October 1973 when Arab oil exporters embargoed countries that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War. But you could see it coming months before then. The Government denied any possibility of a crisis as early as July: a sure sign one was on the way.

In early August, they sent out ration books to Post Offices. They said it was “only a precaution”, and even at the end of October, Trade and Industry Secretary Peter Walker was still assuring us there was no need for concern. We had stocks for another 79 days, with 30 more on the way in tankers on the ocean. By then, no one believed it and there was an outbreak of ‘fill-up fever’. We began to keep our tanks full to the brim, with extra in cans for emergencies. This made things worse. Petrol stations began to limit how much you could buy so as not to run out.

|

| Peter Walker lays down the law |

It was, in any case, illegal to store more than four gallons at home. Even then it had to be in the correct containers (such as my Paddy Hopkirk can pictured in the earlier post). Some thought they could ignore these rules. In Banbury, a taxi driver was fined £150 for storing 30 gallons in five-gallon drums in a garage, in Hinckley another man was fined £50 for having 90 gallons in a shed, and in Coventry an engineering rep. who drove 32,000 miles a year was fined £110 for hoarding 148 gallons. They must have spent hours siphoning it through rubber tubing. Some were even found to be storing petrol in cellars and attics, which, fire chiefs correctly warned, was extremely dangerous and could be ignited by a single spark. Simply switching on a light could result in a massive explosion.

On Monday 26th November, the Government announced that petrol coupons would be distributed to motorists from Thursday of that week, again, of course, “only as a precaution”. Coupons were to be issued at Post Offices on different days according to the initial letter of your surname, beginning with A and B on Thursday 29th November.

Postmasters complained. It was one of their busiest days of the year when pensioners collected their Christmas bonuses. Queues spilled out into the streets, swelled by motorists trying to renew their tax discs before the end of the month as they were needed to claim coupons and those that expired on the 30th November would not be accepted after that date despite normally being allowed fourteen days’ grace.

Coupons were then available progressively until names beginning W-Z collected them on the 12th December. Businesses then followed a similar rota. It does not seem to have been made clear what happened if you went late or on a wrong day; I suspect you got your coupons anyway. There were warnings from Scottish postmasters of potential chaos on ‘M’ day, December 6th, because nearly everyone’s name there began with M or Mc. Extra ‘M’ days were allocated in Lewis, Harris, Barra, and North and South Uist.

The coupons were actually left over from the 1967 Arab-Israeli War when they had been printed “as a precaution” but not needed, which was just as well because that war had taken place in June and the coupons were still being printed in December. At least it meant they were ready in good time for 1973.

To claim your coupons, you had to show your vehicle log book and current road tax disc. Motorists in Sheffield were among the first to be booked by traffic wardens for not displaying a tax disc while collecting their coupons.

Your log book was stamped to show your coupons had been issued. It was said some people were getting extra coupons illicitly by claiming to have lost their logbooks and obtaining replacements. It was left to motorists to enter the vehicle registration number on the front of the ration book. Books were therefore not necessarily tied to the vehicle for which they were issued, leading to fears of a black market.

Ration books contained six month’s worth of coupons. Everyone got a basic allowance depending on the size of their engine, so my 848cc Morris Mini (the blue one in the blog banner) fell into the ‘not exceeding 1100cc’ category, allowed four N units and two L units per month. The bigger the engine the more you got, the other categories being 1101-1500cc (they got 6N+2L or 4N+2L on alternate months), 1501-2200cc (7N+3L per month) and 2201cc plus (7N+4L or 7N+3L)*. Motor cycles got less, and buses and lorries more. Essential vehicles and drivers with special priority (doctors, nurses, vets, ministers of religion, welfare workers and some disabled people) could claim extra, and you could apply for a supplementary allowance in cases of severe domestic hardship (e.g. for getting to and from work where there was no public transport).

This all sounds very carefully thought out and precise, except that some Post Offices ran out of some categories of ration books and the Government would not say how many gallons each N and L unit might allow you to buy before rationing actually came in. You could make a guess based on the 1956-57 Suez crisis when motorists had a basic allowance for around 200 miles per month, but by 1973 the number of private cars on the road had more than tripled to 13.5 million so it could have been less.

While all this was going on, the miners and electricity workers had begun an overtime ban and the miners then went on strike for a 16.5% pay rise. Prime Minister Edward Heath announced a State of Emergency and the 50 m.p.h. speed limit was made compulsory from the 8th December, with motorists fined for exceeding it. Reduced street lighting brought an increase in petrol theft by siphoning, so we all had to buy locking petrol caps (they were not standard fittings then). Mine is still in a cupboard in the garage. Television broadcasts went off at 10.30 p.m. and the use of electricity for floodlighting and advertising was banned. We were urged to switch off lights and turn down the heating at home, and papers subsequently released under the 30-year rule reveal that the Government even considered making it illegal to heat more than one room. They would have needed officious A.R.P.-like wardens knocking on doors to check your room temperatures. Power cut rotas were drawn up as in the miners’ strike two years earlier and published in regional newspapers, but never implemented. However, from the 1st January 1974, most businesses were only allowed to use electricity on three days per week. It lasted until the 7th March.

I suffered no great hardship myself. At the time I was a mature student for a few futile months at Teacher Training College. I drove in and out of college each day, and further afield on teaching practice, days out walking in the dales and home to my parents at weekends, and was never short of petrol. Rationing was never implemented and my spare can remained full for at least a couple of years. It turned out to be a good investment because four-star doubled in price to around 75p per gallon (16½p per litre) between 1973 and 1975.

In the end, it was indeed only a precaution, but there was real irony to the 1973 Christmas Number One: So here it is Merry Christmas, everybody’s having fun.

* I think these coupon quantities are correct.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)