This year’s Christmas story is a tale of deception gone wrong, from the early nineteen-seventies.

“You idiots, you scoundrels, you rogues and vagabonds! Be sure thy sin will find thee out!”

Brendan’s impression was spot-on. It was as if Grimston Stewart was right there in the room with you spouting his pretentious, second-hand drivel. It was all there: the rhythms, the cadences, the clipped intonation, the rolled ‘r’, the arrogance.

“You riff-raff! You ne’er do wells! You scum of the earth! ...”

Brendan could stretch and twist his face to look as silly and pompous as Grimston too, with all the quirks and mannerisms you didn’t notice until pointed out. You could imagine Grimston in his Noel Coward dressing gown, posturing like some vain intellectual exhibitionist: Oscar Wilde or Aubrey Beardsley, perhaps. The only thing missing was the long cigarette holder.

“I shall not dull my palm with felony. Honesty is the best policy.”

Grimston was a fake. He would have you believe his clever quips and jibes were his own invention, but we knew he got them from a dictionary of quotations

hidden in his room. Nick, the other member of our shared house, had a theory he was really called Stuart Grimston but had changed it to Grimston Stewart to sound more impressive. I thought Grimston sounded like a dog’s name. At least it wasn’t hyphenated – not yet.

Whatever his name, we were making the most of his absence. Grimston had left for a winter holiday with wealthy friends, and the shared house was less censorious without him; and noisier. We could stay up late drinking and smoking, playing our guitars, singing vulgar songs, having beer-mat fights and shouting foul language at each other. We could leave the lights on, bottles all over the floor, bins overflowing, the toilet filthy, crumbs on the kitchen table and the sink full of dirty plates, like “the dunghill kind who delight in filth and foul incontinence.” House sharing works best when everyone is compatible, but Grimston, some kind of accountant, did not fit in, the

wayward liberals we were. There is always one.

His absence was fortuitous because the scheme Nick had conceived would have sent him into a torrent of protest, with or without acknowledgement to the Bible, Shakespeare and other luminaries from his dictionary of quotations.

“We shall find ourselves dishonourable graves,” mimicked Brendan.

“Hasn’t anyone thought of this before?” I wondered. “Three hundred quid each just for telling a few stories! It seems so easy.”

“It is,” Nick reassured us, “as long as we think it through properly and don’t say anything stupid ...”

“Les absents ont toujours tort.”

“... like that!”

It certainly seemed a fascinating idea. For Nick, it was a project – an intellectual exercise with a profitable conclusion. Brendan just liked the thought of the money.

Nick went through it again. We were to hide all our valuables in his lock-up garage, disarray the house to give the appearance of a break-in, go back home to our parents for Christmas, and on our return report the burglary to the police and make an ‘authentic’ insurance claim for the loss of our possessions. We congratulated ourselves on the ingenuity. It was so simple – the perfect crime.

We ransacked the house according to plan, broke open the cellar window, forced the locks on our room doors and decanted the contents of drawers and cupboards on to the floor. Late at night we discreetly packed our possessions into Nick’s car and transferred them to the seclusion of his garage: our guitars, my hi-fi, Nick’s bicycle and Brendan’s camera. No one saw us at all.

Back at the house, elated, phase one complete, a big bottle of Strongbow each, we rehearsed our interview with the police.

“Now tell me again,” said Brendan in his best Chief Inspector Barlow voice, “where did you say you were at the time of the break-in?”

“Er – staying with my parents,” I replied unconvincingly.

“I see. Do you have insurance?”

“Yes, thank goodness.”

“It’s an insurance fiddle isn’t it?”

“No, I was away visiting ...”

“Don’t lie to me you piece of filth.”

“Honest! It’s true. I really was ...”

Brendan switched into his Grimston Stewart voice.

“Honest implies a lie. Isn’t that right Chief Inspector Barlow?”

I only hoped the investigator assigned to our case lacked the analytical aggression of television’s Detective Chief Inspector Barlow.

Suddenly I realised we had overlooked one important point, the one critical mistake.

“How do we explain why our rooms have been burgled, but not Grimston’s?”

Nick and Brendan were taken aback. How could we have forgotten that? Either we had really to break into Grimston’s room and steal his stuff, or we had to invite him to join in the scheme. The first seemed a whole level of dishonesty higher than insurance fraud. The second was out of the question, Grimston would never participate.

We stood outside Grimston’s door.

“I am no petty villain,” preached his voice. “You must reinstate the status quo and make good the damage, or I shall report you to Her Majesty’s Constabulary.”

“Shut up Brendan,” I said. “It’s not funny.”

I kicked at Grimston’s door in disgust and turned away, only to turn back on Nick’s gasp. It had not been locked. The door had swung open.

“That’s not like him,” said Brendan, for once using his own voice.

Nick disappeared into the room and quickly identified the reason for the lax security. Grimston had taken most of his things with him. Typical! He trusted no one. All we had to do was tip the remaining contents of his drawers and cupboards on to the floor to give the appearance of a search. There was nothing anyone would have wanted to pinch, but Grimston would believe we really had been burgled.

In one drawer we found the notorious dictionary of quotations. Nick picked it up.

“I think this will have to be stolen,” he said triumphantly.

The plan was exceeding expectations. Not only would Grimston be speechless when he found out about the burglary, he would not be able to look up anything to say about it either.

We could now put phase two into action. The three of us went home for Christmas to secure Barlow-proof alibis. Grimston, returning from holiday, was first back, and went to the phone box to report the crime to “Her Majesty’s Constabulary”. When I got back a bored, solitary policeman was wandering around. I passed off my anxiety as distress. We had to answer one or two simple questions, none of them unexpected. Next day a fingerprint man visited and went through the motions of dusting a powdery mess of graphite on doors, windows, mirrors and drawer handles, but left without finding anything sufficiently well-defined for evidence. We submitted our insurance claim. Grimston even claimed for the loss of his silly dictionary. Well, he had been the one to insist we took out insurance in the first place.

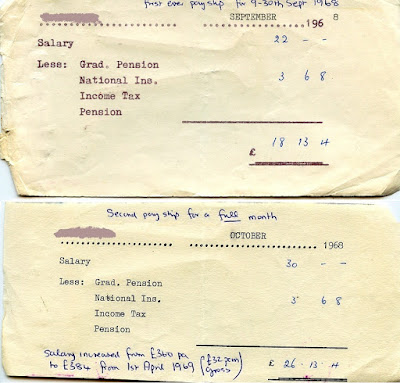

The total value was impressive. The insurance company wanted to see receipts for the most expensive things. We each had a stereo and records, and I had a tape-deck as well. Guitars, fan heaters, cameras, slide projectors, electric toasters, books, clothing, the house television set and Nick’s bicycle brought the total claim to nine hundred and thirteen pounds, over three hundred each after Grimston’s miniscule claim.

And there was a bonus. Within a week Grimston had left. The area was “a den of iniquity unfit for habitation by righteous souls”. There would be no one to ask awkward questions as to how we had recovered our possessions when the time came to move them back.

Luckily, we did not retrieve them immediately. A few days later a detective constable visited the crime scene.

“It’s a good job you were insured,” he said. “There have been a lot of break-ins in this area recently. I have to say that unfortunately there is very little chance of recovering your possessions.”

Afterwards, we judged it safe to go for our things.

Nick had not been to the garage since the day of the ‘crime’. There wasn’t room for his car and in any case, he was worried someone might see inside and become suspicious. So we were already a little apprehensive when we drove round under cover of darkness. Nick turned off his lights and opened the door. It was difficult to see but I knew something was wrong. Nick felt it too.

Nick returned to the car and flashed the lights, flashed them again, and then put them on full beam. The garage was empty. A broken panel at the rear told us what had happened.

Brendan spoke first, in his own voice.

“The world’s full of bloody criminals. We can’t even claim on insurance ’cos we already have.”

I could see Nick’s thoughtful face in the headlights, and then it was he, not Brendan, who began to speak in quotations.

“Our worldly goods are gone away,” he declared. “We are wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities.”

Things were worse than I thought. In that awful moment I realised what had happened to that ridiculous dictionary of quotations.