New Month Old Post: 1st posted 19th February 2019

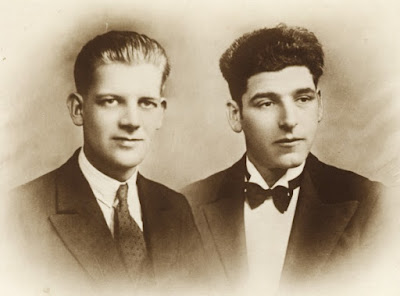

This is Bill and Jack. They had this postcard of themselves made from two separate photographs during the nineteen-thirties. They look like a well-turned-out American songwriting duo: Rogers and Hart or Gershwin and Gershwin, perhaps. Why they had it made, or how they used it, I have no idea.

Bill, on the left, was my grandma’s brother. He remained at home with his parents into his thirties. Jack lived with them. Jack was undoubtedly the livelier of the pair, and Bill, rather his sidekick. In the makeshift pre-war census known as the 1939 Register, Jack is constantly on the go as a window cleaner, transport driver and police despatch rider. Bill is simply a general labourer in a paper mill. People remembered a sign on the gate: “Let Jack Do It”. When Jack played in the village football team, Bill had only a supporting role as treasurer. When Jack played drums in a nineteen-thirties dance band, Bill would sit on stage next to him, even though, as someone remembered, “he did not have a musical bone in his body”.

Bill died aged 33. It may have been linked to smoking. My grandma gave me a box of around 40 complete nineteen-thirties cigarette card sets, which I believe had been collected by Bill.

Jack had Bill buried in one half of a double grave with a single stone surround. He reserved the other half for himself, and had his name inscribed on the vacant plot with the dates to be added later. The stone surround was divided by a small marker bearing the word “Pals”.

I know what many may be thinking, something that would never have been thought in an out-of-the-way, self-contained, nineteen-thirties Yorkshire village. Again, I don’t know, but two years after Bill’s death, Jack got married. It was during the war, somewhere in the Midlands. Jack was thirty-nine and his wife, twenty-two. They returned to Yorkshire and had several children. The names and dates of both Jack and his wife are now inscribed on the once vacant half of the double grave.

Although I never met Bill, I have two memories of Jack. The first was at my grandma’s house when I was no more than four or five. Jack was smoking heavily, talking in a loud voice, agitated about something. Every other word was “bloody”: “bloody” this, “bloody” that, with the occasional “bugger” thrown in. He spat out the words with the cigarette smoke, jerking and shaking his head, making his whole face wobble in emphasis of all he said. I don’t know what it was about but he seemed entirely unconcerned that a young child was watching and listening.

The second time was at a football match seven or eight years later. He was Secretary of the local amateur league for teams such as Thorne Colliery and the railwaymen, pub teams like the Victoria and the Buchanan, village teams including Pollington, Eastrington and Swinefleet, and even a team of Methodists. It was Jack’s duty to present the cup to the winning finalists. All gathered around for the ceremony. I wondered what I was about to hear. Jack made a short speech. His face still wobbled in emphasis of all he said, but he did it without saying “bloody” or “bugger” even once.