Google Analytics

Showing posts with label accents and language. Show all posts

Showing posts with label accents and language. Show all posts

Sunday 10 March 2019

Wednesday 6 March 2019

Castleford

Conversations can be disturbing. They come back to trouble you decades later, especially when they involve some element of social awkwardness, which in my case is quite a lot of conversations.

Not long after taking a job at a university in Scotland over thirty years ago, I was invited to a regular end-of-term gathering at a professor’s house where everyone and everything exuded an air of intellectual wealth and entitlement. Most people there were Scottish, with that precise self-assurance an educated Scottish accent gives you. I felt out of place with my English ears and English voice. I tried to look comfortable in such surrounding.

The professor’s wife, like me, was English – in her case posh plummy English. She had left her brick of a Ph.D. thesis, with its absurdly long title, casually out for all to see on an out-of-the-way occasional table we had to pass, or wait beside, on our way to the loo.

It was only a matter of time before someone was going to bring up the issue of my accent: my “dulcet Yorkshire tones” as they put it. The professor’s wife showed unexpected interest.

“Oh! I’m from Yorkshire too,” she revealed. I was taken in by the hint of something in common.

“Where abouts in Yorkshire?” I asked, predictably.

“C-aaastleford”, she replied, the ‘a’ drawn out as long as the title of her Ph.D. thesis.

Well, you probably know that Yorkshire people have a tendency to blurt straight out what they are thinking, and I did.

“Y’don’t sound as if ya coom from Cassalfud,” I said, in my normal voice of the time.

She looked like she wanted to pick up the thesis and hit me with it.

I wish I could say I passed it off with poise and confidence, but I didn’t. I flinched at every flashback for the next few weeks. I still do, sometimes. It’s like that for some of us who score highly on Asperger tests. At least it means you remember things you otherwise wouldn’t.

I was only invited there the once.

The photograph epitomises how I imagine Castleford was in the nineteen-sixties and nineteen-seventies, when, as in my own Yorkshire home town, the National Coal Board were still recruiting mining apprentices (“Look Ahead Lads!”). If you find the location now on StreetView, the building in the right foreground is the only thing that still remains, barely recognisable. The other buildings have all gone, including what looks like a Tetley’s pub in the row of buildings on the left (they still use the same sign). The cars date the scene to the early nineteen-seventies: from left to right I think they are (all British made) a Triumph Herald, an Austin or Morris 1100, a Ford Escort and possibly an Austin estate on the right. I can hardly begin to make a stab at the cars in the modern picture.

Labels:

1970s,

1980s,

accents and language,

college and university

Thursday 20 December 2018

Get Tret Better

English is a strange thing, especially in its regional forms.

Yesterday, BBC Television News had a report about how insurance companies ramp up premiums so that customers who renew their policies year after year end up paying far more than they should. One poor chap who had kept his home insurance with the same insurer for twenty-one years received a renewal bill of £1,930, but after shopping around he got the same cover for £469.

They asked people at Doncaster Market what they thought about it, including two ladies behind a food stall:

“Well,” said one in comforting Yorkshire tones, “I think it's a disgrace, actually, because I think loyal customers should get tret better.”

“Tret better?” I wanted to rush straight to Doncaster Market, give her a big hug, and sit beside the stall listening to her all day. It’s what my mother would have said.

I’m no grammaticist, but I suppose it’s like met instead of meeted, sat instead of seated, or het instead of heated, as in I’m all het up.

At one time I would have said “tret better” too, but, sadly, I’ve had it educated out of me.

Labels:

2000-2020s,

accents and language,

film television radio,

financial,

mum

Sunday 2 December 2018

Does Anyone Want Some Drinks?

Returning to Yorkshire on the 15:56 First TransPennine Express service yesterday after a family day out in that wonderful city of Liverpool, a man came along the train with the refreshments trolley and asked: “Does anyone want some drinks?”

We wondered how one should answer this oddly-worded question. He seemed to be inviting each passenger to consume several drinks. It seems unlikely that anyone would want, say, a cup of tea, a soft drink and a bottle of water, unless they were very thirsty. And what about snacks? There were a load of those on his trolley too. Weren’t they for sale as well?

“No, but I would like one drink,” might have been an appropriate answer, or perhaps “No, but I would like a packet of crisps.”

There again, he might have been asking whether any one of us wanted to purchase several drinks to be shared amongst our travelling companions, in which case it was extremely perceptive of him to spot that we were travelling as a group.

What should he have asked to take account of all these eventualities?

“Would anyone like any drinks?” is one very minor adjustment that might have worked, although that would exclude snacks. Perhaps TransPennine should therefore radically overhaul their refreshment trolley operative training so that they ask, simply “Refreshments?”

Why does it bother me?

Could it be in any way related to the fact that we were travelling on Diesel Multiple Unit set 185113 and that I’ve always made a mental note of such things?

See also: Andy Burnham, Chris Grayling and the Goole to Leeds Train

Sunday 9 September 2018

Articled Clerk

“You’ll make a lot of money as a Chartered Accountant” was the only thing of substance the headmaster said at the end of grammar school. I could guess what he was really thinking. “Not university calibre.” “Not even college.” Stuck-up southern git!

It was strange that someone so southern had chosen to become a headmaster in such a working-class northern town. He spoke with such judgemental self-assurance you were convinced his pronunciation must be correct and yours miserably deficient: “raarzbriz” instead of “rasp-berries”, “swimming baarthes” rather than “swimmin’ baths”, “campany derrectorre” not “kumpany dye-recter”. It was not universally welcomed.

“You’ve written here that your faarther is a campany derrectorre. What sort of campany derrectorre?”

“He’s got a shop – Millwoods”

“Really? I thought Millwoods was owned by Susan Mellordew’s faarther.”

He appeared not to believe me. Oh to have that conversation again knowing what I know now.

“Perhaps the Mellordews would like others to think that,” I should have said.

Grammar schools were set up to get people into university, or at least teacher training college. Everyone else was a failure to be eased into the grubby world of banking, accountancy or other forms of servility, unless you were a girl, in which case they didn’t really care either way because you would be married with kids in a few years’ time. I didn’t care either. I was quite taken by the idea of making a lot of money, especially as all six of my university choices had given me straight rejections.

At least the local accountants wanted me. They phoned my dad to change my mind about going off to a job in Leeds. “He’ll get just as good experience here,” they told him, but he decided not to pass the message on, as if they wanted me but he didn’t.

I had tried York first. The area training coordinator at The Red House sent me round to Peat, Marwick and Mitchell, one of the biggest and most powerful firms in the country (as KPMG they still are), to be interviewed by another stuck-up posh git whose laconic disinterest oozed the impression that he had indeed made a great deal of money. He would have got on just fine with my headmaster. Not for the last time did I feel I might have done better had I been to Bootham’s or Queen Ethelburga’s.* Real chip-on-the-shoulder stuff!

The Leeds firm were more down to earth. Their offices were in what had once been a cloth warehouse with large airy windows; less depressing than the pokey accommodation of the other firms. A simple half-hour chat with one of the partners, during which I managed to avoid showing too much stupidity, and the job was mine: five years as an articled clerk. I started on the 9th September, 1968; exactly fifty years ago today.

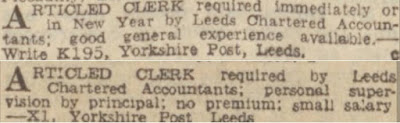

The thing is though, in those days, firms of accountants were desperate for articled clerks. At face value it was attractive: a form of indentured apprenticeship under which a qualified accountant undertakes to inculcate an articled clerk into the principles and practices of the profession. In reality it was cheap labour. They sold it to school leavers through discreet ads in the situations vacant columns, next to those for hair restorers and varicose veins. “Leaving school? Why not become a Chartered Accountant?” It would not have looked out of place if they had added: “No one need know; confidentiality guaranteed.”

Ads were discreet because accountants were not allowed to tout for business, although as things began to change, the bigger firms pushed the boundaries with larger, more flamboyant offerings designed by expensive agencies. One of the most memorable went: “Some think Wart Prouserhice is just as good as Horst Whiterpart, but we know it’s best at Price Waterhouse.”

Today, accountancy training places are so sought after they won’t even look at you unless you have at least a 2:1 and an impressive portfolio of extra-curricular leadership activities – an internship in the House of Commons; volunteering with Ebola victims in Africa; representing Great Britain in the Winter Olympics; that kind of thing. You might then get invited to a day of written tests and observed activities, and if successful to a nerve-racking interview panel. Those who went to Bootham’s or Queen Ethelburga’s might then be offered a place. Back in the nineteen-sixties, five ‘O’ levels and you were in.

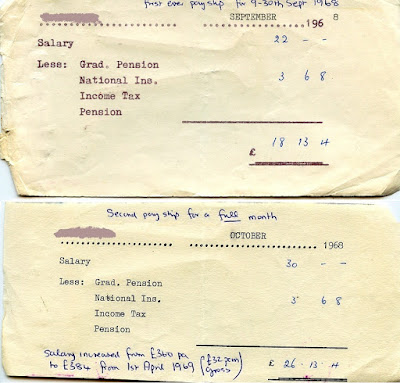

Not so many years beforehand, articled clerks had been expected to pay a premium for the privilege of the job. At least by 1968 you got a salary, if that’s what you could call it. Mine was £360 per annum.

Really? Well yes. Here are my first two pay slips. The first covers from the 9th to the 30th September, 1968, i.e. twenty-two thirtieths of a month. So 22/30 x 360/12 equals a straight £22, with a deduction of £3 6s 8d for National Insurance, leaving £18 13s 4d for my first three weeks’ pay. My first full month’s take-home pay was £26 13s 4d. I didn’t have to pay tax because I only started work in September, but I did after April when I got a £2 per month rise. It doesn’t look any better even when adjusted for inflation – £26 13s 4d in 1968 is the equivalent of around £400 today, less than half the minimum wage for an eighteen year-old.

I never did become a Chartered Accountant. I stuck it for a few years, failed a few exams, and then escaped to university. Would I have fared better in my parochial home town of canners, carriers, barbers, farmers, shippers and shopkeepers? I might have fitted in – like a pile of coke outside the gas works – but maybe not. Thirty years later, one lad from my class at school who did go to work with the local firm ended up as one of the senior partners in charge of the whole outfit. He did make a lot of money.

* Fee paying boarding schools near York.

Labels:

1960s,

accents and language,

accountancy,

dad,

Leeds,

school

Thursday 28 September 2017

People who can‘t say ‘ull

The BBC Radio Four announcer said this afternoon that in half an hour there would be a programme about the 2017 City of Culture.

“I know where he means” I thought, but then he mystified me by saying it was about the Ezzall area of the city. It took me a moment to realise he meant ‘essle. There is a difference. In trying to mimic the local accent, he had over-emphasised the initial E.

Like the friend I had when I worked in Scotland. No matter how hard she tried, no matter how many times I demonstrated, she could never say ‘ull without it sounding wrong. The initial U was too strong, almost beginning with a glottal stop. The voice-onset came too soon. It’s a soft gentle U after the dropped H, not a hard one.

It seems to my ears that people not from the region cannot say ‘ull or ‘essle properly, or for that matter ‘owden, ‘edon, ‘altemprice or ‘umber. Please, unless you grew up in East Yorkshire or thereabouts, don’t try. Just put the H in.

The programme, incidentally, was Hull 2017: The Spirit of Hessle Road.

“I know where he means” I thought, but then he mystified me by saying it was about the Ezzall area of the city. It took me a moment to realise he meant ‘essle. There is a difference. In trying to mimic the local accent, he had over-emphasised the initial E.

Like the friend I had when I worked in Scotland. No matter how hard she tried, no matter how many times I demonstrated, she could never say ‘ull without it sounding wrong. The initial U was too strong, almost beginning with a glottal stop. The voice-onset came too soon. It’s a soft gentle U after the dropped H, not a hard one.

It seems to my ears that people not from the region cannot say ‘ull or ‘essle properly, or for that matter ‘owden, ‘edon, ‘altemprice or ‘umber. Please, unless you grew up in East Yorkshire or thereabouts, don’t try. Just put the H in.

The programme, incidentally, was Hull 2017: The Spirit of Hessle Road.

Labels:

2000-2020s,

accents and language,

Hull,

humour,

Rawcliffe/Goole/Howden

Friday 28 April 2017

Le Tour de Yorkshire

In the early nineteen-sixties, I remember going along to Boothferry Bridge to watch The Milk Race pass by – a national cycling event also known as the Tour of Britain, sponsored by the now defunct Milk Marketing Board. Some blokes on racing bikes flashed past amidst the everyday traffic and it was all over in less than a minute. It wasn’t worth the bother. Cycling must be the sport with the biggest disconnect between doing (riding a bike is fun) and watching (tedious). I’ve never been to a cycling event since.

So it’s irritating to find the Tour de Yorkshire imposed on us this weekend, with roads closed most of the day bringing maximum disruption to our activities, just to see people on bicyles for a couple of minutes. I’m keeping well away.

And they call it the / le “Tour de Yorkshire”. What pretentious twaddle! Et le moins dit à propos de la côte de Silsden et de la côte de Wigtwizzle, mieux c'est.*

Surely, if it’s in Yorkshire, shouldn’t it be called t’baiyk race roun’ t ‘roo-ads?

So it’s irritating to find the Tour de Yorkshire imposed on us this weekend, with roads closed most of the day bringing maximum disruption to our activities, just to see people on bicyles for a couple of minutes. I’m keeping well away.

And they call it the / le “Tour de Yorkshire”. What pretentious twaddle! Et le moins dit à propos de la côte de Silsden et de la côte de Wigtwizzle, mieux c'est.*

Surely, if it’s in Yorkshire, shouldn’t it be called t’baiyk race roun’ t ‘roo-ads?

* The less said about “côte de Silsden” and “côte de

Wigtwizzle” the better.

Labels:

1960s,

accents and language,

bicycles,

humour,

Rawcliffe/Goole/Howden

Wednesday 2 September 2015

Old Tools

Not long after my parents married in 1946, my maternal grandfather took my father to one side and, on account of the fact that his new son-in-law travelled in ladies underwear (so to speak) rather than having some more practical and manly occupation, told him, “Sither, th’d better ’ave these,” and gave him a set of tools. No doubt the items he passed on were surplus to his needs having acquired and inherited a considerable collection over his forty-five years.

Those tools, both my father’s and my grandfather’s, became very familiar to me. My grandfather’s tools remained in his garden shed-cum-workshop, and after he had died at what was even then an abysmally young age, I would sneak in to ‘play’ with his wood brace and drill bits, his awls and gimlets, his planes, chisels, hammers and mallets, and other tools I couldn’t identify, all logically arranged on purpose made hooks, racks and shelves. Some may have been handed down from his own grandfather, who had worked with steam engines on barges in the 1870s. Both would have been as appalled by my lack of respect for them as by my father’s mistreatment of the items he had been given.

My grandfather’s immaculate collection of tools eventually went to one of my uncles to be misused by his children, but my father’s neglected assortment are among the jumble of tools I now have to sort out, having over the years, just like my grandfather, bought, acquired and inherited my own surplus.

Now rusty and unloved, so many of them bring back lost associations. There are the bicycle spanners and tyre levers I watched my father use to adjust saddles, remove wheels and mend punctures (see Dad's Thursday Helper). There are thicker spanners and tyre levers from the toolkits of long-ago scrapped motor vehicles – his firm’s delivery vans – some marked ‘Bedford’, another labelled ‘Austin’, all in defunct British Standard Whitworth sizes.

There are broken files and sets of hard-handled pliers now so stiff it takes stronger hands than mine to pull them open. They carry the trademark of Elliott Lucas of Cannock which once made around half of all the pliers and pincers sold in the United Kingdom.

A group of wooden-handled, triangular scrapers reminds me of the time my father acquired a blowlamp and painstakingly scraped layers of old paint off the skirting board in the back room. Those old scissors are the ones my mother used for dead-heading the flowers in the garden.

There is a thick metal punch, its top battered down from when I used it to chip out a groove in the concrete under the door of the yellow shed I had taken over, to form a base for a ridge of cement to act as a barrier to the rainwater that pooled in, although it never worked. That was in 1965 – I know because I remember scoring the date in the top of the cement, it being my birthday.

Among the screwdrivers with bent or rounded blades is one with its wooden handle splintered down to half its original size through being bashed with a hammer when it served as a substitute cold chisel. Other screwdrivers were misused as makeshift levers and scrapers. One of them, the most damaged and least usable of them all, was left by a mechanic under the bonnet of one of my first cars after it had been in for repair. My father and I weren’t the only serial tool-abusers in town.

For the last thirty years or so, my father’s tools lived in an blue metal tool box. The bottom is now rusted through despite the amount of oil and grease covering everything inside, soaking into the wooden handles and attracting a filthy film of old paint, grease, grit and bits of insects. I had to wipe them clean before I could begin to sort them.

In addition there are my own tools, once new but now seemingly as old as my father’s. There are tools for painting and wallpapering, woodworking, home plumbing and electrical work, the legacy of years as a home owner. There are sets of AF and Metric spanners, feeler gauges, a spark-plug spanner, a brake spanner and other specialist implements from the days I serviced my own old bangers. There is a set of miniature silver tools that once came in a pouch designed to be carried in a car glove-box, which were always useless, consisting of an adjustable spanner that did not grip, a hinged set of spanners that were all the same size, and a handle with interchangeable screwdriver blades which somehow failed to fit any screw I ever wanted to turn.

And now – the event that forces me to sort them all out after all this time – I have acquired yet more tools, this time from my mother-in-law, some old and worn, others as good as new, little used and much better than mine.

I am afraid that most of the tools photographed, together with the rusty blue toolbox, are destined for the metal recycling skip, having checked ebay and found them to be effectively valueless.

Two particularly satisfying things I will keep.

“That’s my daddy’s ruler,” my wife said when we unearthed this thirty-six inch Rabone boxwood 1375 folding ruler in my mother-in-law’s garage. These beautiful devices were used widely before the invention of the ubiquitous retractable tape measure. Its four sections can be folded down to a single nine-inch length, or opened out to an arrow-straight yard long rule. There seem to be plenty still left around, probably because they are much too satisfying to throw away.

“That’s my daddy’s oil can,” is what I could have said when we found it in the cardboard box that came from my father’s garage nearly ten years ago. He used to fill it with used engine oil and like the spanners mentioned above, it may originally have been from an ancient motor vehicle tool kit. This type of oil can predated the present day tins with built-in plastic spouts. Unfortunately, because of damage, it would now only serve its original function with a sawn-off shortened spout, so I’ve cleaned it out with a hot solution of washing powder to keep as an object of interest. I recently saw a similar one in a Cotswolds antique shop for £100.

Good. That’s the tools sorted. Now for my accumulation of nails, screws, washers, brackets, hinges, piping, wiring, fuses, electric plugs, wall plugs, bath plugs, coat hooks, cup hooks, curtain hooks, door handles, fork ’andles and other bits and pieces. On second thoughts, it can wait a few more years. If I leave it long enough it will be someone else’s problem. Either that or open my own branch of Screwfix.

Labels:

1940s,

1950s,

accents and language,

dad,

DIY,

family (childhood)

Wednesday 24 December 2014

Reel-to-Reel Recordings

Dad turns to the microphone on the mantlepiece, clears his throat and adopts a suitable air of gravitas.

“I will now read some of my favourite poems,” he says in his most dignified voice. The sound of muted giggling emanates from me and my brother sitting on the floor next to the tape recorder.

“Ernest Dowson’s Vitae Summa Brevis,” he announces.

The noises in the background become audible whispers.

“What’s he on about?”

“He says Ernest Dowson had some Ryvita for his breakfast.” More snorting and sniggering. Dad continues.

“They are not long, ...”

“What aren’t? Is our Sooty’s tail not long?”

“... the weeping and the laughter, Love and desire and hate:”

The disruption intensifies as my mother bangs on the window and shouts something muffled from the yard outside. Dad struggles to keep going.

“I think they have no portion in us ...”

My mother enters the room and interrupts loudly.

“When I tell you your dinner’s ready, it’s ready, and you come straight away.”

The recording ends.

Would Dowson’s melancholy poetry and vivid phrases ever have emerged from out of his misty dream had he married and had such an unsupportive, philistine family?

Christmas 1962 – an unbelievable fifty-two years ago – was when my dad came into some money and bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder. It was really for the whole family, but as I was the only one who knew how it worked it was effectively mine, my parents being too old to understand such modern technology and my brother too young to be trusted with it. The next door neighbour was appalled at the idea of such an extravagant present for a twelve year old. Her eyebrows must have shot even further through the ceiling a month or so later when the new car arrived. As I said, my dad had inherited a useful sum of money.

The Philips EL 3541, as the YouTube video shows, was beautifully designed and built, part of the last triumphant surge of valve-based electronics before the transistor revolution. In contrasting greys and white, preceding the stark ubiquity of brushed aluminium, the case and controls had pleasantly curved profiles. The main buttons were smooth and soft, but clunked and clicked with a satisfyingly businesslike sound. The whole thing felt substantial and robust, with a reassuringly heavy-duty carrying strap. It looked a bit like a wide, trustworthy face with large eyes and beautiful white teeth.

People are beginning to re-discover that using and owning physical objects like tape machines and vinyl records can have value, a sensory quality you don’t get with digital downloads. Why did we ever throw these things away?

This particular model was a four track machine, which means it could make four separate recordings on each reel of tape, two in each direction. The machine is shown with five inch reels (13cm) which typically held nine hundred feet (270m) of tape, but it could accommodate up to seven inch reels (18cm) holding eighteen hundred feet (540m). Tapes ran at a speed of three and three quarter inches per second (9.5 cm/sec)* which means that a five inch tape ran for around forty-five minutes and a seven inch tape around ninety minutes. So using four tracks, you could record for up to three hours on a five inch tape, and six hours on a seven inch tape, although you did have to turn over and re-thread tapes manually at the end of each track. A seven inch tape could therefore hold the equivalent of eight long playing (LP) records or albums, provided they weren’t excessively long, which they weren’t before the late nineteen-sixties.

Just to complicate things a little more, these numbers are for ‘long play’ tapes. You could also get ‘double play’ (2,400 feet on a 7 inch reel) and ‘triple play’ (3,600 feet on a 7 inch reel) but these were thinner and prone to breaking or stretching, so I avoided them. There were also thicker ‘standard play’ tapes, and five and three quarter inch reels as well, but the boxes always showed the tape length so it wasn’t as confusing as it sounds. Most of my tapes were Long Play five or seven inch reels. Believe it or not, I still have them, some from 1962 and 1963.

Some of the earliest recordings picked up a high pitched whistle through the microphone. Later I used to remove the backs from the television and record player to connect wires to the loudspeaker terminals. It got rid of the whistle but it could so easily have got rid of me as well.

The earliest recording I have is still on the five inch tape that came with the machine, from the Light Programme at four o’clock on the 30th December, 1962, ‘Pick of the 1962 Pops’ – “David Jacobs plays some of the hit records from the past twelve months**.” It starts off with Frankie Vaughan’s ‘Tower of Strength’, which had been number one in December, 1961, and then runs through a further twenty-three top three singles of 1962, ending with Elvis Presley’s ‘Return to Sender’. There are plenty of solo singers but not a British pop group among them. It was only a month or two before the end of that year that I’d first heard of the Beatles when ‘Love Me Do’ came on 208 Radio Luxembourg late one night on my transistor radio underneath the bedclothes.

I recorded the corresponding shows for 1963, 1964 and 1965, and for 1966 to 1969 the ‘Top of the Pops’ year end shows from television (audio only)**. This was a period when the old guard of solo singers such as Cliff Richard, Elvis Presley and Frank Ifield appeared less and less in the charts, displaced by emerging new groups like Jerry and the Pacemakers, The Searchers and of course The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. In 1964 the top spot was almost entirely British, Roy Orbison being the only exception.

I owned only two actual LP records myself, ‘The Hits of the Animals’ (an export version bought in Belgium) and Georgie Fame’s ‘Sweet Things’, but built up a considerable collection of recordings by exchange borrowing with friends. It included Donovan, Manfred Mann, Sandie Shaw, Jim Reeves, and the early Beatles and Rolling Stones LPs, although I later erased most of them by over-recording with music borrowed from the magnificent collection at Leeds Public Library.

I began to develop an interest in classical music. A friend’s elder brother had gone off to university leaving his record collection unattended in their front room. Attracted first by the sumptuous excitement of George Gershwin’s ‘An American in Paris’ and ‘Rhapsody in Blue’, I sampled the rest of the collection, such as the Beethoven symphonies and Mozart’s ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’. They all went on my tapes. I don’t think my friend’s brother ever knew. Thanks Mike!

On one tape there are early recordings of broadcast comedy shows: the Christmas ‘I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again’ from 1970; the first four programmes ever of ‘I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue’ from 1972** which were for many years lost to the B.B.C and possibly still are; and audio recordings of early ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ from television. By then I was living in a shared house in Leeds where one of our favourite diversions was transcribing the Python scripts and acting them out.

Like snowy pictures on old videotape, the sound quality has not always lasted well. Perhaps with music this doesn’t really matter as you can always replace it, digitally re-mastered with a clarity that far exceeds the original, and usually in stereo rather than the earlier mono.

But you cannot replace the evocative social and family moments that were captured. Despite surviving in only thin and feeble form, they are irreplaceable beyond value.

At a friend’s house a group of us believed ourselves worthy rivals to the likes of comedians John Cleese, Tim Brooke Taylor and Bill Oddie. We wrote and recorded our own biblically themed comedy, ‘The Old Testacles’, most of it unrepeatable because of scurrilous allusions to countless teachers and pupils then at school, and of course the relentless uninhibited adolescent filth.

But the family moments remain the most poignant, like my grandma feeding my baby cousin on her knee, speaking in a village accent fashioned and formed before the First War:

“Shout o’Sooty. You shout. What does Sooty say? ’Ere y’are. He du’n’t say ’ere y’are. Who’s go’r all t’butter? Yer gre-ased up aren’t yer? Oh heck! Eat it up nice. Yes you eat that up. Yer can’t come up, me shirt buttons‘ll be runnin’ all ove’ we-re n’t the’? Deary me to dae!”

Most precious of all are my dad’s unselfconscious performances. Because his grandad had been a sea captain, he claimed an inherited, natural aptitude in the delivery and interpretation of sea shanties. He announces the well-known windlass and capstan shanty, ‘Bound for the Rio Grande’, and begins to sing:

“I’ll sing you a song of the fish of the sea...” followed by a hesitant pause, followed by complete breakdown into helpless uncontrollable laughter.

I am on these tapes too, embarrassing in my unbroken voice and long gone local accent, as my dad begins another poem:

“Miss J. Hunter Dunn. Miss J. Hunter Dunn. Furnish’d and burnish’d by Aldershot sun...”

As before, my brother and I whisper to each other in the background.

“It’s about Miss J. Hunter’s bum.”

Again we all collapse into irrepressible laughter and my dad is unable to continue further.

* In comparison, cassette tapes, which became successful from the late nineteen-sixties, ran at one and seven eighth inches per second. They had to go slower because they were so short. However, the slower the recording speed the poorer the recording quality, which meant that cassettes were prone to distortion and background noise which had to be corrected by electronic sticking plaster such as the Dolby noise reduction system. But cassettes were so compact and convenient to handle that they soon supplanted reel-to-reel and the rival but troublesome tape cartridge system which emerged around the same time as cassettes.

** It would be a shame if these recordings were lost for ever so I have digitised them, put them on YouTube with private access (you can only hear them if you have the URLs) and linked them below.

“I will now read some of my favourite poems,” he says in his most dignified voice. The sound of muted giggling emanates from me and my brother sitting on the floor next to the tape recorder.

“Ernest Dowson’s Vitae Summa Brevis,” he announces.

The noises in the background become audible whispers.

“What’s he on about?”

“He says Ernest Dowson had some Ryvita for his breakfast.” More snorting and sniggering. Dad continues.

“They are not long, ...”

“What aren’t? Is our Sooty’s tail not long?”

“... the weeping and the laughter, Love and desire and hate:”

The disruption intensifies as my mother bangs on the window and shouts something muffled from the yard outside. Dad struggles to keep going.

“I think they have no portion in us ...”

My mother enters the room and interrupts loudly.

“When I tell you your dinner’s ready, it’s ready, and you come straight away.”

The recording ends.

Would Dowson’s melancholy poetry and vivid phrases ever have emerged from out of his misty dream had he married and had such an unsupportive, philistine family?

Christmas 1962 – an unbelievable fifty-two years ago – was when my dad came into some money and bought a reel-to-reel tape recorder. It was really for the whole family, but as I was the only one who knew how it worked it was effectively mine, my parents being too old to understand such modern technology and my brother too young to be trusted with it. The next door neighbour was appalled at the idea of such an extravagant present for a twelve year old. Her eyebrows must have shot even further through the ceiling a month or so later when the new car arrived. As I said, my dad had inherited a useful sum of money.

The Philips EL 3541, as the YouTube video shows, was beautifully designed and built, part of the last triumphant surge of valve-based electronics before the transistor revolution. In contrasting greys and white, preceding the stark ubiquity of brushed aluminium, the case and controls had pleasantly curved profiles. The main buttons were smooth and soft, but clunked and clicked with a satisfyingly businesslike sound. The whole thing felt substantial and robust, with a reassuringly heavy-duty carrying strap. It looked a bit like a wide, trustworthy face with large eyes and beautiful white teeth.

People are beginning to re-discover that using and owning physical objects like tape machines and vinyl records can have value, a sensory quality you don’t get with digital downloads. Why did we ever throw these things away?

This particular model was a four track machine, which means it could make four separate recordings on each reel of tape, two in each direction. The machine is shown with five inch reels (13cm) which typically held nine hundred feet (270m) of tape, but it could accommodate up to seven inch reels (18cm) holding eighteen hundred feet (540m). Tapes ran at a speed of three and three quarter inches per second (9.5 cm/sec)* which means that a five inch tape ran for around forty-five minutes and a seven inch tape around ninety minutes. So using four tracks, you could record for up to three hours on a five inch tape, and six hours on a seven inch tape, although you did have to turn over and re-thread tapes manually at the end of each track. A seven inch tape could therefore hold the equivalent of eight long playing (LP) records or albums, provided they weren’t excessively long, which they weren’t before the late nineteen-sixties.

Just to complicate things a little more, these numbers are for ‘long play’ tapes. You could also get ‘double play’ (2,400 feet on a 7 inch reel) and ‘triple play’ (3,600 feet on a 7 inch reel) but these were thinner and prone to breaking or stretching, so I avoided them. There were also thicker ‘standard play’ tapes, and five and three quarter inch reels as well, but the boxes always showed the tape length so it wasn’t as confusing as it sounds. Most of my tapes were Long Play five or seven inch reels. Believe it or not, I still have them, some from 1962 and 1963.

Some of the earliest recordings picked up a high pitched whistle through the microphone. Later I used to remove the backs from the television and record player to connect wires to the loudspeaker terminals. It got rid of the whistle but it could so easily have got rid of me as well.

The earliest recording I have is still on the five inch tape that came with the machine, from the Light Programme at four o’clock on the 30th December, 1962, ‘Pick of the 1962 Pops’ – “David Jacobs plays some of the hit records from the past twelve months**.” It starts off with Frankie Vaughan’s ‘Tower of Strength’, which had been number one in December, 1961, and then runs through a further twenty-three top three singles of 1962, ending with Elvis Presley’s ‘Return to Sender’. There are plenty of solo singers but not a British pop group among them. It was only a month or two before the end of that year that I’d first heard of the Beatles when ‘Love Me Do’ came on 208 Radio Luxembourg late one night on my transistor radio underneath the bedclothes.

I recorded the corresponding shows for 1963, 1964 and 1965, and for 1966 to 1969 the ‘Top of the Pops’ year end shows from television (audio only)**. This was a period when the old guard of solo singers such as Cliff Richard, Elvis Presley and Frank Ifield appeared less and less in the charts, displaced by emerging new groups like Jerry and the Pacemakers, The Searchers and of course The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. In 1964 the top spot was almost entirely British, Roy Orbison being the only exception.

I owned only two actual LP records myself, ‘The Hits of the Animals’ (an export version bought in Belgium) and Georgie Fame’s ‘Sweet Things’, but built up a considerable collection of recordings by exchange borrowing with friends. It included Donovan, Manfred Mann, Sandie Shaw, Jim Reeves, and the early Beatles and Rolling Stones LPs, although I later erased most of them by over-recording with music borrowed from the magnificent collection at Leeds Public Library.

I began to develop an interest in classical music. A friend’s elder brother had gone off to university leaving his record collection unattended in their front room. Attracted first by the sumptuous excitement of George Gershwin’s ‘An American in Paris’ and ‘Rhapsody in Blue’, I sampled the rest of the collection, such as the Beethoven symphonies and Mozart’s ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’. They all went on my tapes. I don’t think my friend’s brother ever knew. Thanks Mike!

On one tape there are early recordings of broadcast comedy shows: the Christmas ‘I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again’ from 1970; the first four programmes ever of ‘I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue’ from 1972** which were for many years lost to the B.B.C and possibly still are; and audio recordings of early ‘Monty Python’s Flying Circus’ from television. By then I was living in a shared house in Leeds where one of our favourite diversions was transcribing the Python scripts and acting them out.

Like snowy pictures on old videotape, the sound quality has not always lasted well. Perhaps with music this doesn’t really matter as you can always replace it, digitally re-mastered with a clarity that far exceeds the original, and usually in stereo rather than the earlier mono.

But you cannot replace the evocative social and family moments that were captured. Despite surviving in only thin and feeble form, they are irreplaceable beyond value.

At a friend’s house a group of us believed ourselves worthy rivals to the likes of comedians John Cleese, Tim Brooke Taylor and Bill Oddie. We wrote and recorded our own biblically themed comedy, ‘The Old Testacles’, most of it unrepeatable because of scurrilous allusions to countless teachers and pupils then at school, and of course the relentless uninhibited adolescent filth.

But the family moments remain the most poignant, like my grandma feeding my baby cousin on her knee, speaking in a village accent fashioned and formed before the First War:

“Shout o’Sooty. You shout. What does Sooty say? ’Ere y’are. He du’n’t say ’ere y’are. Who’s go’r all t’butter? Yer gre-ased up aren’t yer? Oh heck! Eat it up nice. Yes you eat that up. Yer can’t come up, me shirt buttons‘ll be runnin’ all ove’ we-re n’t the’? Deary me to dae!”

Most precious of all are my dad’s unselfconscious performances. Because his grandad had been a sea captain, he claimed an inherited, natural aptitude in the delivery and interpretation of sea shanties. He announces the well-known windlass and capstan shanty, ‘Bound for the Rio Grande’, and begins to sing:

“I’ll sing you a song of the fish of the sea...” followed by a hesitant pause, followed by complete breakdown into helpless uncontrollable laughter.

I am on these tapes too, embarrassing in my unbroken voice and long gone local accent, as my dad begins another poem:

“Miss J. Hunter Dunn. Miss J. Hunter Dunn. Furnish’d and burnish’d by Aldershot sun...”

As before, my brother and I whisper to each other in the background.

“It’s about Miss J. Hunter’s bum.”

Again we all collapse into irrepressible laughter and my dad is unable to continue further.

* In comparison, cassette tapes, which became successful from the late nineteen-sixties, ran at one and seven eighth inches per second. They had to go slower because they were so short. However, the slower the recording speed the poorer the recording quality, which meant that cassettes were prone to distortion and background noise which had to be corrected by electronic sticking plaster such as the Dolby noise reduction system. But cassettes were so compact and convenient to handle that they soon supplanted reel-to-reel and the rival but troublesome tape cartridge system which emerged around the same time as cassettes.

** It would be a shame if these recordings were lost for ever so I have digitised them, put them on YouTube with private access (you can only hear them if you have the URLs) and linked them below.

- I'm Sorry I'll Read That Again ( ISIRTA ) 1970 Christmas Show 30th December 1970

- I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue ( ISIHAC ) Series 1 Programme 1 11th and 13th April 1972

- I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue ( ISIHAC ) Series 1 Programme 2 18th and 20th April 1972

- I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue ( ISIHAC ) Series 1 Programme 3 25th and 27th April 1972

- I'm Sorry I Haven't a Clue ( ISIHAC ) Series 1 Programme 4 2nd and 4th May 1972

- Pick of the 1962 Pops presented by David Jacobs on The Light Programme, 30th December 1962 at 4.00 p.m.

- Pick of the Pops 1963 (presenter unknown but it might be Don Moss)

Pick of the Pops 1964 presented by Alan Freeman on The Light Programme, 20th December 1964 at 5.00 p.m. - Pick of the Pops 1965 presented by Alan Freeman on The Light Programme, 26th December 1964 at 4.00 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1966 Part 1 BBC1 26th December 1966 at 6.15 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1966 Part 2 BBC1 27th December 1966 at 6.17 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1967 Part 1 BBC1 25th December 1967 at 2.05 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1967 Part 2 BBC1 26th December 1967 at 5.25 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1968 Part 1 BBC1 25th December 1968 at 1.25 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1968 Part 2 BBC1 26th December 1968 at 6.35 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1969 Part 1 BBC1 25th December 1969 at 2.15 p.m.

- Top of the Pops 1969 Part 2 BBC1 26th December 1969 at 6.20 p.m.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)