(first posted 20th September 2016)

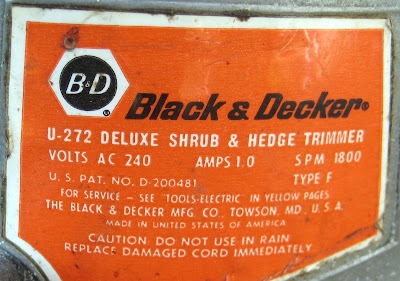

The Black & Decker D470 (U-272) Hedge Trimmer

If you want the kids to cut the hedge and mow the lawn, get them some dangerous power tools and they’ll do it happily while you’re at work. On no account stay home to watch or they won’t do it. Or if they do, they’ll make it look so risky you’ll have to do it yourself.

My brother and I fell for it. We moved to a house with a six-foot high hedge all along the side. We had to cut both sides because it was next to a field. Dad came

home with two seriously businesslike items of equipment: an

Atco petrol mower and a Black & Decker electric hedge trimmer with a

sixteen-inch blade. The mower, to which I owe a useful understanding

of engines, particularly the operation of the clutch, is long gone, but

the hedge trimmer is in my shed. It still works, and I still use it.

Electric hedge trimmers are brutal pieces of equipment. They cause more than three thousand injuries in the U.K. every year, mainly lacerated fingers and electric shock. After all, they are designed to cut through twigs the thickness of your fingers. Today they boast numerous safety features. They have two switches to ensure you keep both hands on the machine at all times, and the blades stop the instant either switch is released. They have blade extensions: fixed teeth which extend beyond the cutting blades so you cannot hurt yourself by accidentally brushing the trimmer against your leg. They have cable protection such as coiling and a belt clip to stop you cutting through it. They have guards to protect your hands from flying or falling debris.

Not only that, they also come with pages of warnings against the ill-advised actions of idiot users. They tell you to wear heavy duty gloves, non-slip shoes and suitable clothing, not to wear a scarf or neck tie, and to tie up long hair. They suggest eye and ear protection, but to be aware that ear protection impedes your ability to hear warnings. They advise against using the trimmer in damp weather, and to watch out for roots and other obstacles you might fall over. And you should always use an RCD (GFCI) circuit breaker.

Your imagination starts to work overtime as you picture the terrible accidents and injuries that might occur. The manufacturers really do think you are an idiot. They say you should never use the equipment while tired or under the influence of drugs or alcohol. You must not permit bystanders, especially children and animals. You should not cut where you cannot see, and should always first check the other side of the hedge you are trimming. Never hold the trimmer with one hand, they say, hinting that those who do might henceforth be left with only one hand to hold it with. And to ensure they have covered everything, including themselves, they tell you never to use the trimmer for any purpose other than for cutting shrubs and hedges. They seem unwilling to specify what these other purposes might be in case you take it as a recommendation. “Do not use the trimmer for shearing sheep,” they could say, “or for grooming your poodle.”

Some manufacturers even include warnings about vibration-induced circulatory problems (white finger disease), and provide advice specifically for those whose heart pacemakers might be affected by the magnetic fields around the motor. And all of this is before they get on to things that might go wrong with petrol driven trimmers and their toxic exhaust fumes and inflammable fuel, which I suppose would have applied to the motor mower my brother and I used to enjoy unsupervised.

The warnings seem so comprehensive they must be based on real accidents

and incidents that have occurred over the years since home power tools

emerged in the nineteen-sixties. Did someone, somewhere, magnetically disrupt their heart pacemaker and drop down dead? Did

someone else, in their business suit straight from the office,

catch up their necktie and die through strangulation? Could you really

chop up your pet cat hiding at the other side of the hedge? And did some simpleton, under the influence of drugs or alcohol, imagine their hedge trimmer as a light sabre, and prance down the garden like Obi-Wan Kenobi to be electrocuted when the power cord tightened around their ankle and tripped them into the fish pond?

So, just how many of these safety features do you think are

designed into the 1968 Black & Decker D470 (or U-272 in the United

States) electric hedge trimmer? Practically none of course, save for blade extensions and a few warnings. The

manufacturers thought it more important to tell you about its power,

speed and ruggedness, and the sharpness of the tempered spring steel

blade. There is nothing to prevent you from using it one-handed, and it will keep going even when you put it down.

One-handed is actually useful: you can reach further without

having to move your step-ladder.

When you switch off it takes two or three seconds to stop. That is why my brother did have an accident. At home on his own one summer afternoon aged about fifteen he helpfully thought he would trim the hedge. He caught the end of his finger in the blade and had to phone Mum at work because he thought he might need to go to hospital, which he did. He had cut about a third of the way into the side of his nail and only noticed when his arm began to feel wet.

Maybe I shouldn’t use it, but I do. It may be so old as not even to get a mention on the Black & Decker web site, but why buy a new one when it is still good? Modern ones are so feeble they need replacing within ten years. This one has already lasted over fifty.

In any case, hedge trimmers are only the third most frequent cause of garden injuries requiring hospital treatment. Far more people are hurt by lawn mowers and even by plant pots.

|

| Instruction sheet for the Black & Decker D460 and D470 (U-272 or 8120) hedge trimmers |