Emptying the household waste baskets, I interrupted my son’s video call. He continues to work at home most days. He had put on a smart shirt and tie, and was talking to some important-looking blokes in suits.

“Sorry,” I apologised when I went back later.

“We were in conference with coun-sel,” he explained. That’s how he said it: “coun-sel,” with too much emphasis on the ‘e’ of the second syllable.

He could see I was looking to mock him. “Just emptying the bas-kets,” I was about to say.

“I know it sounds pretentious,” he said. “I thought I would never say it like that, but we have to avoid confusing coun-sel with coun-cil. It wouldn’t do to be asked to phone the council and to phone the counsel instead, not at the rates they charge.”

“It’s like when I started work,” I said, dredging up a memory from the distant past as usual.

I told him about two people checking over a set of accounts to make sure they had been typed correctly. The one reading out loud from the handwritten draft kept saying things like “thir-tie” and “for-tie” instead of thirty and forty. I thought it sounded silly until it was pointed out that if the typist had typed thirteen in place of thirty, or the other way round, it might be misheard and wrongly passed as correct. Soon, I was pronouncing all my -ties and -teens too. Some you didn’t really need to change, such as twenty because it would never be confused with twelve, but we changed it anyway: “Twen-tie pounds, fif-teen shillings and eleven pence.”

“That would be so easy to carry through into everyday life,” he said. “You don’t usually talk about barristers outside work, but we’re always talking numbers. You could end up saying it without thinking. We deal with about thir-tie or for-tie coun-sel and thirt-tie or for-tie coun-cils.”

“It’s so powerful,” I said, “that even when you tell someone about it, they start doing it themselves, even after fifty years.”

“Fif-tie,” he corrected me.

Google Analytics

Showing posts with label accountancy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label accountancy. Show all posts

Wednesday 23 September 2020

Ties Teens and Sells

Saturday 1 August 2020

Partners and Seniors

(First posted 6th October, 2015. 1,050 words)

Andrew and I were speaking in hushed voices, trying to look as if we were working.

“G-eight”

“Splash”

“B-nine”

“Miss”

“G-nine”

“You’ve hit Mr. Hawkwind.”

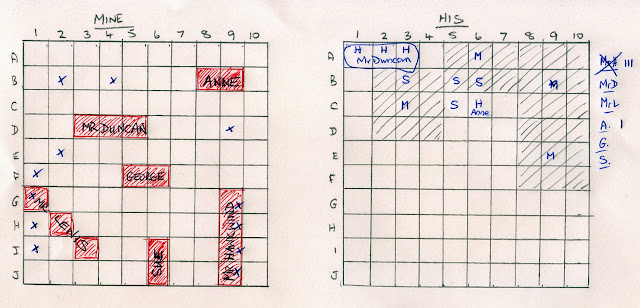

We were playing Partners and Seniors. It was based on Battleships, a pencil and paper game for two players.

In Battleships, each player draws two 10 x 10 grids for their own and their opponent’s fleets of warships, and positions their own fleet secretly in their own grid. Typically, they would have an aircraft carrier occupying five squares, a battleship occupying four, a destroyer and a submarine of three squares each, and a minesweeper occupying two. Neither player should be able to see the other’s grids.

The objective is to sink your opponent’s fleet before they sink yours. There are many variations but we played it as follows. Players take turns to shoot by naming a square in the opponent’s grid. If the square is occupied by one of the opponent’s ships then it is announced as a ‘hit’. If the square is adjacent to an opponent’s ship it is a ‘splash’. If the square is neither occupied nor adjacent it is a ‘miss’. A ship is sunk when all its squares have been hit. Players use their second 10 x 10 grid to record the results of their shots and to decide where to target subsequent shots.

Except we weren’t playing Battleships. Our game had evolved into Partners and Seniors. In place of warships we had Chartered Accountants. Instead of aircraft carriers, destroyers and minesweepers, we had partners, seniors and articled clerks from the firm where we worked. Mr. Hawkwind was one of the partners. He occupied four squares.

We were working out of the office on the most mind-numbing of all the audits we did. You could be there for months putting ticks on ledger cards. It was like disappearing off the face of the earth.

The client was a cloth merchants, an old family firm. They bought rolls of cloth from the manufacturers in every weight, weave, colour, stripe and herringbone imaginable, and re-sold it in suit lengths – the amount needed to make men’s bespoke two-piece or three-piece suits, with or without extra pairs of trousers. The rolls of cloth were stored elsewhere in the building, away from the damaging effects of heat and light. The cool, shadowy stillness of the warehouse had a strange musty smell: a mixture of dyes, preservatives and the scent of the cloth itself.

The firm supplied just about every tailor and outfitter in the country. In other words, they had a lot of customers: twenty trolleys full. For each customer there were one or more yellow sales ledger cards around eight by ten inches in size. The cards were arranged alphabetically in boxes on long-legged, wheeled trolleys like miniature babies’ prams. They referred to them as buses. “Have you seen the ‘B’ bus?” “Could I have the ‘QR’ bus when you’ve finished?”

Some of the office staff had been there for decades, from the days when most clerical jobs were done by men. They all still wore suits and ties, and kept their jackets on all day. Only the office manager, in the room next to ours, worked in his shirtsleeves. He was not an attractive sight: a fearsome, grossly overweight man who always left his unpleasant outdoor shoes, or in winter his stinking wellington boots, beside the radiator.

One of the clerks, in his mid-forties, all worry-lines, teeth and thick glasses, would have been tall had he stood upright, but was bent over from years at a desk. As he stooped to push the ledger buses, his jacket draped itself around the cards as if trying to consume them.

One Friday afternoon we listened, able to overhear the office manager tell the clerk, completely out of the blue, that he was no longer needed. “You realise this is absolutely no reflection on you in any way whatsoever,” he tried to reassure him, as if it made things better. The clerk seemed unable to reply. A week or two later his job was taken by a new girl straight from school.

The business was beginning to struggle and trying to cut costs. Demand for made-to-measure suits was falling because of changing fashions and cheaper, ready-made, ‘off-the-peg’ garments. One floor of the warehouse was now empty. Within not so many years the family owners would decide to give up the ghost and lease the building to the old adversary: the Inland Revenue.

But that was in the future and the firm still had a few years left to run. As auditors, we were required to check that every sale the firm had made during the year had been correctly recorded on the correct ledger card. So for several weeks each year, a couple of articled clerks would spend their days ticking off the cards against the order books and sales invoices. Then, to ensure they received an appropriate breadth of professional experience, they would go through all the incoming payments and tick those off against the ledger cards too. One year you would use a red pen, the following year a green, and then back to red again. The exhilaration was tangible. You really looked forward to getting up in a morning.

What made the task seem even more superfluous was that the ledger cards were partly computerised. They were printed by machine, and each yellow card carried three dark-brown, machine-readable, magnetic stripes to record all the transactions. It was an early, primitive system, but really, wouldn’t some kind of statistical sampling been sufficient to ensure the cards were reasonably accurate? Any mistakes that crept in could have been corrected as and when they were discovered. The firm must have wanted everything checked by the auditors. Articled clerks were paid a pittance so it didn’t cost a lot. Perhaps they needed to keep tabs on the inexperienced staff they were now taking on.

I never did find an error. That is not to say there weren’t any, but the job was so soporific that any I came across would probably have got ticked correct anyway.

Is there any wonder we invented diversions such as Partners and Seniors and firing rubber bands at paper cups to brighten up the day?

“J-nine”

“You’ve just sunk Mr. Hawkwind.”

Mr. Hawkwind would have sunk us if we’d been caught.

Andrew and I were speaking in hushed voices, trying to look as if we were working.

“G-eight”

“Splash”

“B-nine”

“Miss”

“G-nine”

“You’ve hit Mr. Hawkwind.”

We were playing Partners and Seniors. It was based on Battleships, a pencil and paper game for two players.

In Battleships, each player draws two 10 x 10 grids for their own and their opponent’s fleets of warships, and positions their own fleet secretly in their own grid. Typically, they would have an aircraft carrier occupying five squares, a battleship occupying four, a destroyer and a submarine of three squares each, and a minesweeper occupying two. Neither player should be able to see the other’s grids.

The objective is to sink your opponent’s fleet before they sink yours. There are many variations but we played it as follows. Players take turns to shoot by naming a square in the opponent’s grid. If the square is occupied by one of the opponent’s ships then it is announced as a ‘hit’. If the square is adjacent to an opponent’s ship it is a ‘splash’. If the square is neither occupied nor adjacent it is a ‘miss’. A ship is sunk when all its squares have been hit. Players use their second 10 x 10 grid to record the results of their shots and to decide where to target subsequent shots.

Except we weren’t playing Battleships. Our game had evolved into Partners and Seniors. In place of warships we had Chartered Accountants. Instead of aircraft carriers, destroyers and minesweepers, we had partners, seniors and articled clerks from the firm where we worked. Mr. Hawkwind was one of the partners. He occupied four squares.

We were working out of the office on the most mind-numbing of all the audits we did. You could be there for months putting ticks on ledger cards. It was like disappearing off the face of the earth.

The client was a cloth merchants, an old family firm. They bought rolls of cloth from the manufacturers in every weight, weave, colour, stripe and herringbone imaginable, and re-sold it in suit lengths – the amount needed to make men’s bespoke two-piece or three-piece suits, with or without extra pairs of trousers. The rolls of cloth were stored elsewhere in the building, away from the damaging effects of heat and light. The cool, shadowy stillness of the warehouse had a strange musty smell: a mixture of dyes, preservatives and the scent of the cloth itself.

The firm supplied just about every tailor and outfitter in the country. In other words, they had a lot of customers: twenty trolleys full. For each customer there were one or more yellow sales ledger cards around eight by ten inches in size. The cards were arranged alphabetically in boxes on long-legged, wheeled trolleys like miniature babies’ prams. They referred to them as buses. “Have you seen the ‘B’ bus?” “Could I have the ‘QR’ bus when you’ve finished?”

Some of the office staff had been there for decades, from the days when most clerical jobs were done by men. They all still wore suits and ties, and kept their jackets on all day. Only the office manager, in the room next to ours, worked in his shirtsleeves. He was not an attractive sight: a fearsome, grossly overweight man who always left his unpleasant outdoor shoes, or in winter his stinking wellington boots, beside the radiator.

One of the clerks, in his mid-forties, all worry-lines, teeth and thick glasses, would have been tall had he stood upright, but was bent over from years at a desk. As he stooped to push the ledger buses, his jacket draped itself around the cards as if trying to consume them.

One Friday afternoon we listened, able to overhear the office manager tell the clerk, completely out of the blue, that he was no longer needed. “You realise this is absolutely no reflection on you in any way whatsoever,” he tried to reassure him, as if it made things better. The clerk seemed unable to reply. A week or two later his job was taken by a new girl straight from school.

The business was beginning to struggle and trying to cut costs. Demand for made-to-measure suits was falling because of changing fashions and cheaper, ready-made, ‘off-the-peg’ garments. One floor of the warehouse was now empty. Within not so many years the family owners would decide to give up the ghost and lease the building to the old adversary: the Inland Revenue.

But that was in the future and the firm still had a few years left to run. As auditors, we were required to check that every sale the firm had made during the year had been correctly recorded on the correct ledger card. So for several weeks each year, a couple of articled clerks would spend their days ticking off the cards against the order books and sales invoices. Then, to ensure they received an appropriate breadth of professional experience, they would go through all the incoming payments and tick those off against the ledger cards too. One year you would use a red pen, the following year a green, and then back to red again. The exhilaration was tangible. You really looked forward to getting up in a morning.

What made the task seem even more superfluous was that the ledger cards were partly computerised. They were printed by machine, and each yellow card carried three dark-brown, machine-readable, magnetic stripes to record all the transactions. It was an early, primitive system, but really, wouldn’t some kind of statistical sampling been sufficient to ensure the cards were reasonably accurate? Any mistakes that crept in could have been corrected as and when they were discovered. The firm must have wanted everything checked by the auditors. Articled clerks were paid a pittance so it didn’t cost a lot. Perhaps they needed to keep tabs on the inexperienced staff they were now taking on.

I never did find an error. That is not to say there weren’t any, but the job was so soporific that any I came across would probably have got ticked correct anyway.

Is there any wonder we invented diversions such as Partners and Seniors and firing rubber bands at paper cups to brighten up the day?

“J-nine”

“You’ve just sunk Mr. Hawkwind.”

Mr. Hawkwind would have sunk us if we’d been caught.

Wednesday 19 February 2020

The Compton Road Library

|

| Leeds Compton Road Library in the 1980s |

This ‘memoir’ started as a kind of autobiographical attempt to understand how things changed during my time and how I got to where I am, a record for posterity in the forlorn and vainglorious misbelief that someone might one day be interested. I hope it is not too tedious to return to this idea now and again.

One thing I wonder about is how I fell into such an agreeable career in computing and universities after badly messing up three previous chances: failed ‘A’ levels, abandoned accountancy training and student teacher dropout. Fortunately, for post-war baby boomers, chopping and changing was easier than for any other generation before or since.

At twenty-four I was in a run-down shared house and ordinary office job, a lowly clerk with a Leeds clothing manufacturer. It was pleasant enough: home at five, no exams, no correspondence courses, no expectations. It was the largest clothing factory in Europe: cheap suits, nice canteen, warm sausage rolls on the tea break trolley and three hours in the pub every Friday afternoon. You could idle your whole life away. One lad just four years older had already done fourteen years. Real old-timers still talked fondly of Sir Montague, the firm’s founder, and crossed off their days to retirement on the calendar.

With my record what else could I do? Backtrack? Repeat the same things? They said to take the Cost and Management Accountants exams but I barely went through the motions. Eighteen months drifted by. Yet in that time I made progress – seemingly by doing nothing much at all.

Along the road was the tranquil lunchtime retreat of the Compton Road Library, an L-shaped building on the corner with Harehills Lane: the adult library in one wing, the children’s in the other, always warm, always silent, a pervading smell of floor polish throughout. Like all libraries then, they still used the 1895 Browne Issue System: the Pinterest photograph shows the catalogue drawers and tray of readers’ tickets holding cards from books out on loan.

It seemed far more extensive than the picture shows. I got through three or four books a week. It felt like a displacement activity but some left quite an impression. What did I read all that time ago?

There were walking and mountaineering books. Chris Bonington’s I Chose to Climb and The Next Horizon really caught my imagination. I acted them out on walks, scrambled up mountains, bought a Minivan, grew a beard and tried to write things. I took W. A. Poucher’s The Scottish Peaks, a treasure trove of routes and photographs, to Glen Brittle in Skye in the Minivan door pocket and got it soaked. It looked so awful I daren’t take it back, so said I’d lost it and had to pay £1. I’ve still got its stained and curly pages.

There were biographies and autobiographies. I dreamt of escaping like a hermit to some isolated part of Scotland, like Gavin Maxwell in Ring of Bright Water. I tried to emulate R. F. Delderfield who mentions in For My Own Amusement that as a young writer he had been advised to write character sketches of people he knew: “mental photography” he called it. I wondered what it might be like in a garret in Paris struggling to be a writer like V. S. Pritchett in Midnight Oil, “a free man in Paris, unfettered and alive,” as Joni Mitchell put it.

I was unimpressed by Jonathan Aitken’s The Young Meteors in which he interviewed over two hundred leading lights of pop music, film, television, art, photography, clothing, design, politics and business from nineteen-sixties ‘swinging’ London. Some were truly talented but many had either known the right people or just been lucky.

There was fiction: A. J. Cronin, O. Henry and more – anything so long as it was not accountancy.

And all the time I was asking “could I do that?”, “could I be like this?”, “could I write like that?”

We reach a point in our lives where we need to construct an identity for ourselves: to decide who we would like to be and who not. Some manage it as teenagers, others later and a few possibly never. Some get there gradually, others in leaps and bounds. It might take no conscience effort or be a tortured, soul-searching experience. It can take several attempts. For me, it was definitely late, bounding and tortured with false starts.

“It’s a good career, accountancy. Stick at it. You’ll be all right once you’re qualified,” they said, but I was reading about people who had made their own way.

I was never going to chuck everything in for a Parisian garret or Scottish hermitage, but back came the idea of becoming a mature student: at university, not a return to Teacher Training College. The only way would be to take ‘A’ Levels again, a daunting prospect. I approached temp agencies to work flexibly while resitting them, and handed in my notice.

“Don’t cock it up again,” said one of the few supportive friends I had left, mock anguish on his face as he imagined the consequences.

“Course not,” I said with pretend confidence, not too sure.

One thing I am sure of though. A decade or so earlier there would have been no chance. In all likelihood, it would have been national service, back to where I came from, a mundane job and family responsibilities sooner rather than later. Ties. Restrictions. Few opportunities. I doubt I would get as many breaks now, either.

Labels:

1970s,

accountancy,

college and university,

influences,

Leeds,

reading and poetry

Saturday 1 February 2020

The Vauxhall Griffin

(first posted 13th August, 2017)

We were out of the office, auditing the books of a small Vauxhall dealership in Selby. The owner thought Vauxhalls nothing short of wonderful: the Viva, the Victor, the Ventora, the greatest value, the most reliable, the most beautiful cars you could buy. Why would anyone consider anything else? He told us to watch out for the new Vauxhall television advert to be shown for the first time that evening. It was going to be incredible.

The following morning he was seething.

“Did you see it last night? Bloody awful! I don’t know how they expect that to sell any cars. A great puffy bloke leaping around in tights! Who the hell’s going to buy a Vauxhall after that?” I wanted to ask whether he and his staff would be wearing the costume too.

Watching again now I can see what he meant. This dubious Jack-in-the-Green-type character, loitering behind bushes in what looks like the gardens of a crematorium, seems the kind of guy who might have difficulty passing a DBS check. What on earth was Vauxhall thinking?

Along with lots of other dealers, the owner was straight on the phone to Vauxhall and the ad was pulled within the week. I never thought I’d see it again. The company must surely have tried to erase it permanently from the history books. Yet like all things embarrassing, it has resurfaced on the internet.

Most commentators on YouTube dislike it too. They describe the character as creepy: “scares the kids...”, “... and the adults”, “if that thing appeared on my Vauxhall it would get shot”, “talk about a marketing mistake”.

Yet having now seen it a few times, I wonder whether Vauxhall should have persisted. Is the griffin any less disagreeable than the meerkats, dogs or opera singers of today’s ads? We might have warmed to him. We might have begun to find him likeable and amusing. The supercilious catchphrase “Like me!” might have caught on.

The actor was Julian Orchard in one of his typical roles: what Wikipedia describes as a gangling, effete and effeminate dandy. With his long horse-face he was one of the best and funniest comedy support actors in the country. He reminds me a little of the comedian Larry Grayson who before the nineteen-seventies was considered too outrageous for television. Perhaps we weren’t quite ready for this kind of campness in 1973.

Imagine a different outcome, the country taking the griffin to heart, a series of griffin ads: “You’re never alone with a griffin”, “Put a griffin in your tank”. Imagine a family of cuddly griffin toys, plastic griffin figurines free with every gallon of petrol, a griffin hit song on Top of the Pops, children in griffin outfits and Julian Orchard making his fortune. Sadly, he died in 1979 aged only 49.

The more I watch the ad the more I like it. It’s brilliant. Ahead of its time: “Like me!”

|

| Summer 1973 Vauxhall Griffin advert (click to play) |

We were out of the office, auditing the books of a small Vauxhall dealership in Selby. The owner thought Vauxhalls nothing short of wonderful: the Viva, the Victor, the Ventora, the greatest value, the most reliable, the most beautiful cars you could buy. Why would anyone consider anything else? He told us to watch out for the new Vauxhall television advert to be shown for the first time that evening. It was going to be incredible.

The following morning he was seething.

“Did you see it last night? Bloody awful! I don’t know how they expect that to sell any cars. A great puffy bloke leaping around in tights! Who the hell’s going to buy a Vauxhall after that?” I wanted to ask whether he and his staff would be wearing the costume too.

Watching again now I can see what he meant. This dubious Jack-in-the-Green-type character, loitering behind bushes in what looks like the gardens of a crematorium, seems the kind of guy who might have difficulty passing a DBS check. What on earth was Vauxhall thinking?

Along with lots of other dealers, the owner was straight on the phone to Vauxhall and the ad was pulled within the week. I never thought I’d see it again. The company must surely have tried to erase it permanently from the history books. Yet like all things embarrassing, it has resurfaced on the internet.

Most commentators on YouTube dislike it too. They describe the character as creepy: “scares the kids...”, “... and the adults”, “if that thing appeared on my Vauxhall it would get shot”, “talk about a marketing mistake”.

Yet having now seen it a few times, I wonder whether Vauxhall should have persisted. Is the griffin any less disagreeable than the meerkats, dogs or opera singers of today’s ads? We might have warmed to him. We might have begun to find him likeable and amusing. The supercilious catchphrase “Like me!” might have caught on.

The actor was Julian Orchard in one of his typical roles: what Wikipedia describes as a gangling, effete and effeminate dandy. With his long horse-face he was one of the best and funniest comedy support actors in the country. He reminds me a little of the comedian Larry Grayson who before the nineteen-seventies was considered too outrageous for television. Perhaps we weren’t quite ready for this kind of campness in 1973.

Imagine a different outcome, the country taking the griffin to heart, a series of griffin ads: “You’re never alone with a griffin”, “Put a griffin in your tank”. Imagine a family of cuddly griffin toys, plastic griffin figurines free with every gallon of petrol, a griffin hit song on Top of the Pops, children in griffin outfits and Julian Orchard making his fortune. Sadly, he died in 1979 aged only 49.

The more I watch the ad the more I like it. It’s brilliant. Ahead of its time: “Like me!”

Sunday 19 January 2020

Biology Made Simple

(This is not a review. I wouldn’t want to say whether the book is any good

or not. I simply picked it off the shelf where

it has lodged unopened for half a century.)

A book to take you back to the third form (if only), year 9 as now known, two years before ‘O’ Level, the year you were 14. There you are again, head down, sketching and labelling diagrams of amoeba and the human heart, drawing flow charts of the carbon cycle and learning the names of digestive enzymes.

I loved it. I had the kind of dysfunctional, over-active memory that absorbed the names of anatomical structures and physiological processes like protozoan pseudopodia engulfing scraps of food. Two of us were way better than everyone else. There was, let’s called her Hermione, always first in class tests, and me, always one or two marks behind.

But I had a secret weapon. I must have been the only pupil with a tape recorder at home, or at least the only one devious enough to ask my mother to record a radio programme we were to hear in class in preparation for an essay. Mine was bloody brilliant – better than Hermione’s.

Then it became ‘Biology Made Difficult’. That year, Biology in the first term was not examined until the end of the third (terms 2 and 3 were Physics and Chemistry). That’s a long time to have to remember it. You know what happens. Too much messing about, thinking about the wrong things, lack of planning, lack of attention and in my case, well, let’s say poor mental health, meant I didn’t revise for the exam. My end of year report completes the tale. Biology: position in class 2nd; position in exam 25th; teacher’s comment “a disappointing exam result”. For the next two years, the ‘O’ Level years, I found myself in second-stream Biology where messing about and thinking about the wrong things were a way of life, especially if you wanted people to like you. Low grades for all of us. Idiot!

Still, I took Biology at ‘A’ Level and failed, and when I later chucked accountancy to train as a teacher, Biology was my main subject. That’s when I bought the book: a note inside records it was the 3rd July, 1973, about three months before starting at what was then called City of Leeds and Carnegie College, and six months before dropping out. It’s hard to believe you could once be accepted to train as a specialist Biology teacher without having passed it at ‘A’ Level; it was enough merely to have studied it.

No one has looked at the book since. It has been an absolute joy paying it the attention I should have paid then. Goodness, the things it tells you. It’s a bit like a Bill Bryson book without the exaggeration and contrived jokes. It doesn’t need them. It has its own miracles and wonder. Such as that we create and destroy an incredible 10 million* red blood cells every second. Ten million! Every second! That’s 864,000 million per day. Even at that rate it takes over 100 days to replace them all. And then there’s the horror. Such as hookworm. You really wouldn’t want to pick that up, the way it gets into the blood and burrows from the lungs to the windpipe to be coughed up and swallowed to grow in your gut.

And in Chapter 5: ‘Cycles of Life’, pp57-58, there is this. I am guilty of barefaced breach of copyright here, but Extinction Rebellion says it’s all right to break the law to draw attention to environmental issues.

That is what we knew then. In fact, there is a whole chapter expanding upon the preventative and curative measures listed. It was originally published in 1956 and revised in 1967. Despite not mentioning plastic or climate change or unlimited population growth, it lists so many other ways we upset the balance of nature through our “ignorance, carelessness or ruthlessness … in a given area”. Was it too much of a mental leap to understand that “given area” could mean the whole planet? We should all have been paying more attention.

So, an interesting trip down memory lane. It may be “biology made simple”, there were some things I wanted to read more about, it isn’t modern biology with all that nasty cell chemistry, but I enjoyed it. Best of all, I don’t have to learn it now.

*A bit of Googling suggests this may be an overestimate, the correct figure being a still very impressive 2.4 million red blood cells per second, about a quarter of the number given in the book.

A book to take you back to the third form (if only), year 9 as now known, two years before ‘O’ Level, the year you were 14. There you are again, head down, sketching and labelling diagrams of amoeba and the human heart, drawing flow charts of the carbon cycle and learning the names of digestive enzymes.

I loved it. I had the kind of dysfunctional, over-active memory that absorbed the names of anatomical structures and physiological processes like protozoan pseudopodia engulfing scraps of food. Two of us were way better than everyone else. There was, let’s called her Hermione, always first in class tests, and me, always one or two marks behind.

But I had a secret weapon. I must have been the only pupil with a tape recorder at home, or at least the only one devious enough to ask my mother to record a radio programme we were to hear in class in preparation for an essay. Mine was bloody brilliant – better than Hermione’s.

Then it became ‘Biology Made Difficult’. That year, Biology in the first term was not examined until the end of the third (terms 2 and 3 were Physics and Chemistry). That’s a long time to have to remember it. You know what happens. Too much messing about, thinking about the wrong things, lack of planning, lack of attention and in my case, well, let’s say poor mental health, meant I didn’t revise for the exam. My end of year report completes the tale. Biology: position in class 2nd; position in exam 25th; teacher’s comment “a disappointing exam result”. For the next two years, the ‘O’ Level years, I found myself in second-stream Biology where messing about and thinking about the wrong things were a way of life, especially if you wanted people to like you. Low grades for all of us. Idiot!

Still, I took Biology at ‘A’ Level and failed, and when I later chucked accountancy to train as a teacher, Biology was my main subject. That’s when I bought the book: a note inside records it was the 3rd July, 1973, about three months before starting at what was then called City of Leeds and Carnegie College, and six months before dropping out. It’s hard to believe you could once be accepted to train as a specialist Biology teacher without having passed it at ‘A’ Level; it was enough merely to have studied it.

No one has looked at the book since. It has been an absolute joy paying it the attention I should have paid then. Goodness, the things it tells you. It’s a bit like a Bill Bryson book without the exaggeration and contrived jokes. It doesn’t need them. It has its own miracles and wonder. Such as that we create and destroy an incredible 10 million* red blood cells every second. Ten million! Every second! That’s 864,000 million per day. Even at that rate it takes over 100 days to replace them all. And then there’s the horror. Such as hookworm. You really wouldn’t want to pick that up, the way it gets into the blood and burrows from the lungs to the windpipe to be coughed up and swallowed to grow in your gut.

And in Chapter 5: ‘Cycles of Life’, pp57-58, there is this. I am guilty of barefaced breach of copyright here, but Extinction Rebellion says it’s all right to break the law to draw attention to environmental issues.

That is what we knew then. In fact, there is a whole chapter expanding upon the preventative and curative measures listed. It was originally published in 1956 and revised in 1967. Despite not mentioning plastic or climate change or unlimited population growth, it lists so many other ways we upset the balance of nature through our “ignorance, carelessness or ruthlessness … in a given area”. Was it too much of a mental leap to understand that “given area” could mean the whole planet? We should all have been paying more attention.

So, an interesting trip down memory lane. It may be “biology made simple”, there were some things I wanted to read more about, it isn’t modern biology with all that nasty cell chemistry, but I enjoyed it. Best of all, I don’t have to learn it now.

*A bit of Googling suggests this may be an overestimate, the correct figure being a still very impressive 2.4 million red blood cells per second, about a quarter of the number given in the book.

Friday 22 November 2019

How not to forget PINs

A tip from my accountancy years in the early 1970s.

Price tickets in shops sometimes used to bear codes showing cost prices. Next to the price, say £9.99, you would see something like I.WR, which secretly told senior salespeople that the price the shop had paid for the item was £6.50. It allowed them, if appropriate, to decide what discounts they could give. It could also be used to value the items in stock.

It was based on words or phrases made up of ten different letters, for example:

COLDWINTER

The ten-letter word stands for the numbers 1234567890, so, using COLDWINTER, I.WR represents £6.50.

There were various tweaks to make things more difficult to decipher. An additional letter such as X could be used for repeated numbers such as .00 or .99 so that £10.00 could be coded as CR.RX. Or an interchangeable substitute such as Q could be used for zero, £10.00 becoming CQ.RX. Foreign code word were more secure still, especially in less common languages such as Welsh or Gaellic, because even if someone had collected all the letters they would be hard pressed to put them together and guess the code word.

Some more possibilities:

TAMBOURINE

VOLKSWAGEN

READMYBLOG

UMSCHALTEN

CYFIAWNDER

I use it to keep a note of secret numbers such as credit card PINs. It is not difficult to have two or three credit cards, a couple of debit cards, log-in PINs for phones and computers, not to mentions longer sequences such as customer numbers for online banking, building societies and National Savings. We are told not to use the same PIN more than once and not to write them down. How are we supposed to remember them all?

I do in fact know the PIN for my main card but keep a code book for other numbers. I have sometimes even written PINs on cards in code. I could go so far as to tell you that the PIN for my HSBC card is TPEF. No one can decipher it without the ten-letter code word.

You learn to translate between the letters and numbers quite quickly. It’s good brain exercise and insures against embarrassing senior moments at the shop till. It will keep me going until we are all forced to change to fingerprints or other biometric IDs.

Mind you, you’re stuffed if you forget the secret word.

Price tickets in shops sometimes used to bear codes showing cost prices. Next to the price, say £9.99, you would see something like I.WR, which secretly told senior salespeople that the price the shop had paid for the item was £6.50. It allowed them, if appropriate, to decide what discounts they could give. It could also be used to value the items in stock.

It was based on words or phrases made up of ten different letters, for example:

COLDWINTER

The ten-letter word stands for the numbers 1234567890, so, using COLDWINTER, I.WR represents £6.50.

There were various tweaks to make things more difficult to decipher. An additional letter such as X could be used for repeated numbers such as .00 or .99 so that £10.00 could be coded as CR.RX. Or an interchangeable substitute such as Q could be used for zero, £10.00 becoming CQ.RX. Foreign code word were more secure still, especially in less common languages such as Welsh or Gaellic, because even if someone had collected all the letters they would be hard pressed to put them together and guess the code word.

Some more possibilities:

TAMBOURINE

VOLKSWAGEN

READMYBLOG

UMSCHALTEN

CYFIAWNDER

I use it to keep a note of secret numbers such as credit card PINs. It is not difficult to have two or three credit cards, a couple of debit cards, log-in PINs for phones and computers, not to mentions longer sequences such as customer numbers for online banking, building societies and National Savings. We are told not to use the same PIN more than once and not to write them down. How are we supposed to remember them all?

I do in fact know the PIN for my main card but keep a code book for other numbers. I have sometimes even written PINs on cards in code. I could go so far as to tell you that the PIN for my HSBC card is TPEF. No one can decipher it without the ten-letter code word.

You learn to translate between the letters and numbers quite quickly. It’s good brain exercise and insures against embarrassing senior moments at the shop till. It will keep me going until we are all forced to change to fingerprints or other biometric IDs.

Mind you, you’re stuffed if you forget the secret word.

Saturday 20 July 2019

Where were you?

Sunday, 20th July 1969

To add to all the other bloggers today, I had just hitch-hiked back from Hornsea.

I had been at work almost a year but most of my friends were still in education, either at university or waiting for ‘A’ level results hoping to go. I envied them. One was spending summer at his family’s caravan in Hornsea (see Hornsea Pottery), so on Saturday seven of us set off on scooters to look for him.

We found him where we knew we would, in the Marine Hotel. Later we sat around talking with some lads from Liverpool until two in the morning. On Sunday we got up early and built a driftwood fire on the beach. Most of the others then went off to Bridlington but I had to go to work on Monday, so hitch-hiked back on my own. If the ride there on the back of a scooter had been uncomfortable, part of the ride back at high speed on the pillion of a motorbike was terrifying (no compulsory crash helmets in those days). I also remember walking between lifts through the snobby and exclusive village of Walkington shortly before a police car drew up to investigate reports of a vagrant in the village.

I then saw the BBC coverage of the landing which consisted of little more than James Burke and the ever-excitable Patrick Moore talking over the audio feed from mission control. I did not stay up into the small hours to see the moon walk because I had to be up for the early train to Leeds. In the morning there was just time to see a few images of Armstrong and Aldrin “jumping around on the moon” as my mother put it, before I had to leave. On Monday I was not back to my digs from work in time for blast off so only saw it later on the news. None of the images were very clear anyway, except in the imagination.

As for other “Where were you?” questions my answers are: (i) watching Take Your Pick on Friday, 22nd November 1963, when a news flash caused me to rush to the kitchen to tell Mum; (ii) walking from Manchester Victoria to U.M.I.S.T. on the morning of Tuesday, 9th December 1980, when I saw a newsstand headline; and (iii) checking the Teletext news headlines on the morning of Sunday, 31st August 1997, when I rushed downstairs to tell my wife and son. Not that I cared much about that last one. Should I remember any others?

To add to all the other bloggers today, I had just hitch-hiked back from Hornsea.

I had been at work almost a year but most of my friends were still in education, either at university or waiting for ‘A’ level results hoping to go. I envied them. One was spending summer at his family’s caravan in Hornsea (see Hornsea Pottery), so on Saturday seven of us set off on scooters to look for him.

We found him where we knew we would, in the Marine Hotel. Later we sat around talking with some lads from Liverpool until two in the morning. On Sunday we got up early and built a driftwood fire on the beach. Most of the others then went off to Bridlington but I had to go to work on Monday, so hitch-hiked back on my own. If the ride there on the back of a scooter had been uncomfortable, part of the ride back at high speed on the pillion of a motorbike was terrifying (no compulsory crash helmets in those days). I also remember walking between lifts through the snobby and exclusive village of Walkington shortly before a police car drew up to investigate reports of a vagrant in the village.

I then saw the BBC coverage of the landing which consisted of little more than James Burke and the ever-excitable Patrick Moore talking over the audio feed from mission control. I did not stay up into the small hours to see the moon walk because I had to be up for the early train to Leeds. In the morning there was just time to see a few images of Armstrong and Aldrin “jumping around on the moon” as my mother put it, before I had to leave. On Monday I was not back to my digs from work in time for blast off so only saw it later on the news. None of the images were very clear anyway, except in the imagination.

As for other “Where were you?” questions my answers are: (i) watching Take Your Pick on Friday, 22nd November 1963, when a news flash caused me to rush to the kitchen to tell Mum; (ii) walking from Manchester Victoria to U.M.I.S.T. on the morning of Tuesday, 9th December 1980, when I saw a newsstand headline; and (iii) checking the Teletext news headlines on the morning of Sunday, 31st August 1997, when I rushed downstairs to tell my wife and son. Not that I cared much about that last one. Should I remember any others?

Sunday 14 July 2019

Angry Young Men

Alan Sillitoe: Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (4*)

John Braine: Room at the Top (4*)

Two more nineteen-fifties, angry-young-man novels: tales of northern working-class life set just after the war before the sixties and seventies provided an escape route from lives which would otherwise have been as predetermined as those of our parents. Thank goodness I was not born ten years earlier. I would never have had a chance, let alone a fourth chance after blowing the first three.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning begins with a nauseating scene of drunkenness and extra-marital sex. Arthur Seaton is a lathe operator doing piecework in a Nottingham bicycle factory. He earns good enough money to spend on nice suits and as much as he can drink at weekends. He can certainly drink a lot: eleven pints and seven gins to start, and then fall down a flight of stairs, wake up and drink a lot more and still have enough left to go to bed with a married woman while her husband is away.

In contrast, Joe Lampton in Room at the Top seems more civilised. He moves from the ugly industrial town of Dufton to the pleasant manufacturing town of Warley, both in Yorkshire, to take up a post in the municipal accountant’s department. From his thoughts you know he later becomes a wealthy man and that this is the story of how he got there.

While Arthur is uneducated and lives in the large extended family where he was born, Joe has accountancy qualifications and is making his way alone in a new town. What they have in common is that both are good-looking and clever, and both are trapped. Arthur is set to spend the rest of his life tied to a lathe and Joe will remain a local-government functionary, perhaps a gentler existence but hardly any better-off. White- or blue-collar the same: you slaved for small reward. Both resent it but respond in different ways.

At first, you want Joe to do well. It’s hard living in lodgings where you know no one, I’ve done it. But soon you begin to see into Joe’s vain and selfish mind and don’t much like what you find. He judges people, especially women, on a social scale from 1 to 10 and is determined to shag himself to the top. He starts at the town’s amateur dramatic society where he takes up with a worldly married woman, ten years his elder, for whom he develops some feeling, and also with the innocent high-class daughter of one of the wealthiest men in the town, who he doesn’t really love:

I was the devil of a fellow, I was the lover of a married woman, I was taking out the daughter of one of the richest men in Warley, there wasn’t a damn thing I couldn’t do.Joe’s story leads to tragedy after he gets the wealthy daughter pregnant so he can marry upwards and join her father’s business, and then ditches his married lover who dies in a suicidal drunken car crash. Joe knows he is responsible, leaving an enduring sense of guilt, but it makes him no more likeable.

With Arthur, it’s the other way round. You think he’s disgusting at first but gradually come to understand and even have time for him. He is a rebel fighting against social norms:

I'm me and nobody else; and whatever people think I am or say I am, that's what I'm not, because they don't know a bloody thing about me.Eventually, he is badly beaten by one of the husbands he has been cuckolding and confined to bed for a week. Recovering during a lively, crowded family Christmas, he comes to realise that even a rebel can be happy “where there’s life and there’s people”. At the end of the novel he is courting a single girl and planning to marry, but is never going to knuckle down completely:

And trouble for me it’ll be, fighting every day until I die… with mothers and wives, landlords and gaffers, coppers, army, government… dragged up through the dole and into the war with a gas-mask on your clock, and the sirens rattling into you every night while you rot with scabies in an air-raid shelter. Slung into khaki at eighteen, and when they let you out, you sweat again in a factory, grabbing for an extra pint, doing women at the weekend and getting to know whose husbands are on the night shift, working with rotten guts and an aching spine… well, it’s a good life and a good world, all said and done, if you don’t weaken.Truly an angry young man.

Two and three decades later, I knew the settings of these books. Warley is perhaps Bradford or Bingley where Braine grew up and became a librarian. Life chances had increased for the young by the time I was travelling the mills and factories as an auditor, but I came across hundreds of all ages still stuck in the same old class-bound tram tracks. Things did change. We know now that a real Joe Lampton in a town hall would probably have become moderately successful through local-government expansion. But the one that stepped up through marriage would have had to be pretty smart when his business inevitably went bust.

Later, I lived in Nottingham for five years and remember the local dialect so brilliantly captured in Sillitoe’s novel (shopkeepers used to ask: “D’yer want enythink else duck?”). I went to Goose Fair and drank in The Trip to Jerusalem, and walked the country paths around Wollaton and Strelley where Arthur takes women and goes fishing (the locations are described by The Sillitoe Trail web site).

‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning’ is the only truly working-class story of the four so-called angry-young-man novels I’ve written about (the other two being university lecturer Jim Dixon in Lucky Jim and draughtsman/shop manager Vic Brown in A Kind of Loving; and should I include Billy Liar as well?). A real Arthur Seaton would have faced the hardship of redundancy and the dole when the factories closed. Had I come across anyone like him or his hard-drinking, hard-knuckled family, I wouldn’t have dared go near them. I guess that’s because I did indeed escape and now my family mock when I claim to be working class.

Key to star ratings: 5*** wonderful and hope to read again, 5* wonderful, 4* enjoyed it a lot and would recommend, 3* enjoyable/interesting, 2* didn't enjoy, 1* gave up.

Previous book reviews

Labels:

1950s,

4*,

accountancy,

book reviews,

Leeds,

Nottingham

Wednesday 3 July 2019

250 Words A Minute

Funny what you find to read in holiday cottages.

This year among the usual Readers’ Digests and paperback novels in a well-stocked bookcase we found a history of hymns which gave us an uplifting Sunday morning sing-song, and Teach Yourself Pitmans Shorthand.

No doubt, many will remember using shorthand, but it has long been a mystery to me. In my early working days, bosses dictated letters and reports to secretaries for typing. Secretaries kept up with what was said, no matter how quickly, by writing in shorthand. Journalists also used it to record verbatim court proceedings and interviews. To me, it looked like impenetrable lines of squiggles. It might as well have been in Persian or Arabic.

Not being sufficiently important to dictate to a secretary, I usually had to draft things for typing in ordinary longhand. By the time I’d climbed up the hierarchy we had computers so I had to type content myself. Shorthand remained a dark art.

In the holiday cottage, I left the book out on the breakfast table with a notepad to practice. Obviously, no one is going to learn shorthand in a week but at least I might gain some understanding of how it works.

Pitmans shorthand (there are other forms) uses a system of heavy and light, straight and curved strokes, together with dots, dashes, hooks, loops and circles to represent the sounds of the English language.

Here are some exceedingly basic examples:

It gets much more complicated with marks for other vowels and consonants, for common prefixes and suffixes, and various simplifications, but just with the above you can write:

Even from these simple examples, it is easy to see how shorthand can be written more quickly than longhand. The preface to the book says:

But no, that completely unacceptable feline and sexist remark is wrong. She married Thomas Law in Croydon in 1935 and moved to Glasgow and later to Birmingham. I found these:

What an amazing skill! Especially when combined with high-speed typing. It was clearly equal to skills needed in many higher paid men’s jobs, say, in manufacturing and transport. Yet they were “only” shorthand-typists and paid as such.

Actually, I did once dictate a letter. I remember one phrase exactly. I said, “For the sake of clarity, we set out the details in the table below.” It came out as “For the sake of charity, …” and would have gone off like that to the Inspector of Taxes had a partner not spotted it. I got rollocked for not checking it more carefully.

Since returning from holiday I have been playing with this shorthand transcription resource and can therefore sign my name as:

I can just about see how it works, e.g. the initial ‘T’ and ‘D’, although these are more complex two-syllable words. And no, I didn’t pinch the book from the cottage. I put it back in the bookcase. I got to the end of Lesson 1.

What did you do on your holiday?

This year among the usual Readers’ Digests and paperback novels in a well-stocked bookcase we found a history of hymns which gave us an uplifting Sunday morning sing-song, and Teach Yourself Pitmans Shorthand.

No doubt, many will remember using shorthand, but it has long been a mystery to me. In my early working days, bosses dictated letters and reports to secretaries for typing. Secretaries kept up with what was said, no matter how quickly, by writing in shorthand. Journalists also used it to record verbatim court proceedings and interviews. To me, it looked like impenetrable lines of squiggles. It might as well have been in Persian or Arabic.

Not being sufficiently important to dictate to a secretary, I usually had to draft things for typing in ordinary longhand. By the time I’d climbed up the hierarchy we had computers so I had to type content myself. Shorthand remained a dark art.

In the holiday cottage, I left the book out on the breakfast table with a notepad to practice. Obviously, no one is going to learn shorthand in a week but at least I might gain some understanding of how it works.

Pitmans shorthand (there are other forms) uses a system of heavy and light, straight and curved strokes, together with dots, dashes, hooks, loops and circles to represent the sounds of the English language.

Here are some exceedingly basic examples:

- The ‘p’ sound is represented by a lightly written \ and the similar sounding but voiced ‘b’ by a heavier \

- Similarly, ‘t’ and ‘d’ are represented by a light and heavy | and |

- ‘ch’ and ‘j’ are represented by a light and heavy / and /

- Consonants at the start of words are written above the line and those at the end below.

- Vowels are represented by strokes placed before or after a consonant, such as light and heavy – and – to represent short ‘o’ or long ‘oa’ sounds (i.e. the sounds not the spelling so 'note' and 'boat' are the same).

- ‘s’ is represented by a small loop on either the top or bottom of the consonant depending on whether it occurs before or after.

It gets much more complicated with marks for other vowels and consonants, for common prefixes and suffixes, and various simplifications, but just with the above you can write:

Even from these simple examples, it is easy to see how shorthand can be written more quickly than longhand. The preface to the book says:

The compilers wish to place on record their acknowledgement of the help rendered in the preparation of this volume by Miss Emily D. Smith, only Holder of the National Union of Teachers’ Certificate for shorthand speed writing at 250 words a minute.She achieved this on the 22nd March 1934 during a five-minute test using a passage of 1,250 words. Two hundred and fifty words a minute for five minutes! That’s more than four a second. How can anyone speak that fast to dictate them? She must have spent all her time practising. Perhaps that’s why she was only ‘Miss’ Emily D. Smith.

But no, that completely unacceptable feline and sexist remark is wrong. She married Thomas Law in Croydon in 1935 and moved to Glasgow and later to Birmingham. I found these:

What an amazing skill! Especially when combined with high-speed typing. It was clearly equal to skills needed in many higher paid men’s jobs, say, in manufacturing and transport. Yet they were “only” shorthand-typists and paid as such.

Actually, I did once dictate a letter. I remember one phrase exactly. I said, “For the sake of clarity, we set out the details in the table below.” It came out as “For the sake of charity, …” and would have gone off like that to the Inspector of Taxes had a partner not spotted it. I got rollocked for not checking it more carefully.

Since returning from holiday I have been playing with this shorthand transcription resource and can therefore sign my name as:

I can just about see how it works, e.g. the initial ‘T’ and ‘D’, although these are more complex two-syllable words. And no, I didn’t pinch the book from the cottage. I put it back in the bookcase. I got to the end of Lesson 1.

What did you do on your holiday?

Labels:

1930s,

1970s,

accountancy,

holidays and excursions

Saturday 26 January 2019

Twelve Balls

Things that amused us when we should have been working

I came across a note I made in 1970 (on the right of the notepad, above):

SHINE BALD TOP

BALD SPOT

SLAB DINE

HEAP LIST

It took me a while to remember what it was. Eventually it came back: it was the solution to the twelve balls problem (sometimes known as the twelve coins problem). One of the management staff posed it in November, 1969, when we were auditing Spencer and Halstead, an engineering manufacturer at Ossett. We couldn’t solve it. Insufferably, he wouldn’t tell us the answer until our next visit four months later.

The Problem: You have twelve identical-looking balls (or they could be coins or anything similar). One of them is a forgery and is therefore different in weight to others: it could be heavier or it could be lighter but you do not know which. You have a simple balance to weigh the balls against each other, but you can use it only three times – no more. How do you identify the fake ball and whether it weighs more or less than the others?

Note that you do not know whether the fake is heavier or lighter. If you knew for certain that it was, say, definitely lighter than the others, the problem is slightly different: it becomes a question of how to find a single fake out of nine coins in two weighings, or out of twenty-seven coins in three weighings. This is simpler and is not addressed here.

You may wish to pause to consider it further at this point. Or, if you’ve glazed over already, you may wish to jump to the end to find out about the other notes on the notepad.

* * *

The answer is to label the twelve balls with the letters of the first phrase above, and then weigh them in groups of eight – four against four – as specified in the three pairs of words.

For example, if the three weighings come out as (i) balance (ii) left heavy (iii) right heavy, then you know the faulty ball is not one of those in the first weighing, so it must be H, I, N or E. The second weighing eliminates H which is not there, and because I, N and E are on the light side, one of these must be lighter than all the others. Of these only E is on the light side in the third weighing, so E is the fake, and it is lighter than the others.

I wondered how this could work for all possible answers. Well, first of all, because each weighing can have three possible outcomes – left heavier, right heavier or balance – there are 3 x 3 x 3 i.e. 27 possible outcomes across the three weighings. Secondly, as there are twelve balls, and as we know that only one of them is either heavier or lighter, there are 24 possible answers. So the number of possible outcomes exceeds the number of possible answers, suggesting that each outcome could identify a different answer, with three outcomes unused.

One of the unused outcomes has to be where all three weighings are in balance, because that would mean all balls had identical weight.

Not being one to let this kind of thing pass by without further thought, I could not resist creating the following table (L means left heavy, R means right heavy and B means balance). Hey, some people enjoy crosswords, I enjoy doing this. Get over it!

You can see that the outcomes for heavy balls are mirror images of the outcomes for light balls. Also, the ‘unused outcomes’ are ones which do not occur.

In fact, the table also tells you where to place each ball in the three weighings. Looking just at the left hand column: Ball A should be placed on the left of the balance in all three weighings; Ball O should be placed on the right in the first weighing and omitted from the second and third weighings.

With this insight, we could now create our own mnemonic for the solution. How about:

READ THIS BLOG

READ BITS

BEAR GOLD

THOR SLED

I think it works. It’s just a case of finding a phrase consisting of twelve different letters, and then jiggling the letters and weighing patterns around until you get words.

I wondered why a pair of outcomes is left over: RLL / LRR as well as BBB. It is because the solution only needs 24 rather than the full 26 of the 3 x 3 x 3, i.e. 27 possible outcomes. So could it be used for a thirteenth ball? Unfortunately not, because if you placed a thirteenth ball on the balance you would be weighing six balls against seven each time, which would tell you nothing. However, I think you could use this outcome instead of one of the others provided you switched round other balls to preserve the equality of the three four-against-four weighings.

Could you do four balls in two weighings? Theoretically, this has 8 possible answers with 3 x 3 i.e. 9 outcomes from two weighings. But, you get only a partial solution. You have to weigh one against one each time (with two two-against-two weighings, neither would balance, and five of the nine possible outcomes would be non-occurring). For example, labelling the balls A, B, C and D, and weighing A against B and then A against C:

It identifies all outcomes except when ball D is the fake, which is identified correctly but not whether heavy or light. However, it would work if you had only three balls and two weighings. I suspect this was the starting point for the person who originally formulated the problem.

What if you were allowed four weighings? What, then, would be the maximum number of balls from which you could identify a lighter or heavier fake? There would then be 3 x 3 x 3 x 3, i.e. 81 possible outcomes. Forty balls would have eighty possible answers, but I suspect you would have insufficient non-occurring / unused outcomes to be able to do it.

Well, I’ve worked it out (I told you I’m a loony). Four weighings would allow you to find the fake amongst thirty-nine balls. If you want to know how I did it, look here. It actually gives quite an insight into how the whole things works. It appears there is always a variety of ways to formulate the groups used in the weighings.

What if, rather than just one, there were two fake balls? How would you weigh them then? O.K., this is beginning to go beyond even my limits of pointless curiosity. Proper mathematicians have come up with formulae to show how many balls can be done in N weighings (in the main case considered here it’s ½(3n-1)-1 if you want to know, but it can get a lot more complicated).

It’s clever stuff. Out of the millions of ways in which twelve balls can be weighed against each other, it is genius to realise that you can arrange things so that each combination of outcomes identifies a different solution. And just as brilliant is the realisation that the balls can be labelled with the letters of a phrase so that the three weighings can be selected using pairs of words made from the letters of that phrase. But cleverest of all is whoever it was that came up with the problem in the first place.

* * *

The other notes on the paper, by the way, are also things which amused us during our working hours.

The first is supposedly a telegram sent by a sailor to his wife on returning from a long voyage. It was intended to read “In today, home tonight, lots of love, Rodney” but got garbled during transmission and came out probably as what he was really thinking.

The second refers to a philanderer who took out policies with different insurers to provide for his loved ones. The policy for his baby was with General Accident, and so on.

So, we did not spend our entire time thinking about combinations and permutations. Welcome to the wonderful misogynistic world of business and commerce, 1970.

I came across a note I made in 1970 (on the right of the notepad, above):

SHINE BALD TOP

BALD SPOT

SLAB DINE

HEAP LIST

It took me a while to remember what it was. Eventually it came back: it was the solution to the twelve balls problem (sometimes known as the twelve coins problem). One of the management staff posed it in November, 1969, when we were auditing Spencer and Halstead, an engineering manufacturer at Ossett. We couldn’t solve it. Insufferably, he wouldn’t tell us the answer until our next visit four months later.

The Problem: You have twelve identical-looking balls (or they could be coins or anything similar). One of them is a forgery and is therefore different in weight to others: it could be heavier or it could be lighter but you do not know which. You have a simple balance to weigh the balls against each other, but you can use it only three times – no more. How do you identify the fake ball and whether it weighs more or less than the others?

Note that you do not know whether the fake is heavier or lighter. If you knew for certain that it was, say, definitely lighter than the others, the problem is slightly different: it becomes a question of how to find a single fake out of nine coins in two weighings, or out of twenty-seven coins in three weighings. This is simpler and is not addressed here.

You may wish to pause to consider it further at this point. Or, if you’ve glazed over already, you may wish to jump to the end to find out about the other notes on the notepad.

* * *

The answer is to label the twelve balls with the letters of the first phrase above, and then weigh them in groups of eight – four against four – as specified in the three pairs of words.

For example, if the three weighings come out as (i) balance (ii) left heavy (iii) right heavy, then you know the faulty ball is not one of those in the first weighing, so it must be H, I, N or E. The second weighing eliminates H which is not there, and because I, N and E are on the light side, one of these must be lighter than all the others. Of these only E is on the light side in the third weighing, so E is the fake, and it is lighter than the others.

I wondered how this could work for all possible answers. Well, first of all, because each weighing can have three possible outcomes – left heavier, right heavier or balance – there are 3 x 3 x 3 i.e. 27 possible outcomes across the three weighings. Secondly, as there are twelve balls, and as we know that only one of them is either heavier or lighter, there are 24 possible answers. So the number of possible outcomes exceeds the number of possible answers, suggesting that each outcome could identify a different answer, with three outcomes unused.

One of the unused outcomes has to be where all three weighings are in balance, because that would mean all balls had identical weight.

Not being one to let this kind of thing pass by without further thought, I could not resist creating the following table (L means left heavy, R means right heavy and B means balance). Hey, some people enjoy crosswords, I enjoy doing this. Get over it!

| S heavy = RLR | S light = LRL |

| H heavy = BBL | H light = BBR |

| I heavy = BRR | I light = BLL |

| N heavy = BRB | N light = BLB |

| E heavy = BRL | E light = BLR |

| B heavy = LLB | B light = RRB |

| A heavy = LLL | A light = RRR |

| L heavy = LLR | L light = RRL |

| D heavy = LRB | D light = RLB |

| T heavy = RBR | T light = LBL |

| O heavy = RBB | O light = LBB |

| P heavy = RBL | P light = LBR |

| Not used: BBB, RLL, LRR |

You can see that the outcomes for heavy balls are mirror images of the outcomes for light balls. Also, the ‘unused outcomes’ are ones which do not occur.

In fact, the table also tells you where to place each ball in the three weighings. Looking just at the left hand column: Ball A should be placed on the left of the balance in all three weighings; Ball O should be placed on the right in the first weighing and omitted from the second and third weighings.

With this insight, we could now create our own mnemonic for the solution. How about:

READ THIS BLOG

READ BITS

BEAR GOLD

THOR SLED

I think it works. It’s just a case of finding a phrase consisting of twelve different letters, and then jiggling the letters and weighing patterns around until you get words.

I wondered why a pair of outcomes is left over: RLL / LRR as well as BBB. It is because the solution only needs 24 rather than the full 26 of the 3 x 3 x 3, i.e. 27 possible outcomes. So could it be used for a thirteenth ball? Unfortunately not, because if you placed a thirteenth ball on the balance you would be weighing six balls against seven each time, which would tell you nothing. However, I think you could use this outcome instead of one of the others provided you switched round other balls to preserve the equality of the three four-against-four weighings.

Could you do four balls in two weighings? Theoretically, this has 8 possible answers with 3 x 3 i.e. 9 outcomes from two weighings. But, you get only a partial solution. You have to weigh one against one each time (with two two-against-two weighings, neither would balance, and five of the nine possible outcomes would be non-occurring). For example, labelling the balls A, B, C and D, and weighing A against B and then A against C:

| A heavy = LL | A light = RR | |

| B heavy = RB | B light = LB | |

| C heavy = BR | C light = BL | |

| D heavy =BB | D light = BB (also) | |

| Not used: RL, LR |

It identifies all outcomes except when ball D is the fake, which is identified correctly but not whether heavy or light. However, it would work if you had only three balls and two weighings. I suspect this was the starting point for the person who originally formulated the problem.

What if you were allowed four weighings? What, then, would be the maximum number of balls from which you could identify a lighter or heavier fake? There would then be 3 x 3 x 3 x 3, i.e. 81 possible outcomes. Forty balls would have eighty possible answers, but I suspect you would have insufficient non-occurring / unused outcomes to be able to do it.

Well, I’ve worked it out (I told you I’m a loony). Four weighings would allow you to find the fake amongst thirty-nine balls. If you want to know how I did it, look here. It actually gives quite an insight into how the whole things works. It appears there is always a variety of ways to formulate the groups used in the weighings.

What if, rather than just one, there were two fake balls? How would you weigh them then? O.K., this is beginning to go beyond even my limits of pointless curiosity. Proper mathematicians have come up with formulae to show how many balls can be done in N weighings (in the main case considered here it’s ½(3n-1)-1 if you want to know, but it can get a lot more complicated).

It’s clever stuff. Out of the millions of ways in which twelve balls can be weighed against each other, it is genius to realise that you can arrange things so that each combination of outcomes identifies a different solution. And just as brilliant is the realisation that the balls can be labelled with the letters of a phrase so that the three weighings can be selected using pairs of words made from the letters of that phrase. But cleverest of all is whoever it was that came up with the problem in the first place.

* * *

The other notes on the paper, by the way, are also things which amused us during our working hours.

The first is supposedly a telegram sent by a sailor to his wife on returning from a long voyage. It was intended to read “In today, home tonight, lots of love, Rodney” but got garbled during transmission and came out probably as what he was really thinking.

The second refers to a philanderer who took out policies with different insurers to provide for his loved ones. The policy for his baby was with General Accident, and so on.

So, we did not spend our entire time thinking about combinations and permutations. Welcome to the wonderful misogynistic world of business and commerce, 1970.

Sunday 9 September 2018

Articled Clerk

“You’ll make a lot of money as a Chartered Accountant” was the only thing of substance the headmaster said at the end of grammar school. I could guess what he was really thinking. “Not university calibre.” “Not even college.” Stuck-up southern git!

It was strange that someone so southern had chosen to become a headmaster in such a working-class northern town. He spoke with such judgemental self-assurance you were convinced his pronunciation must be correct and yours miserably deficient: “raarzbriz” instead of “rasp-berries”, “swimming baarthes” rather than “swimmin’ baths”, “campany derrectorre” not “kumpany dye-recter”. It was not universally welcomed.

“You’ve written here that your faarther is a campany derrectorre. What sort of campany derrectorre?”

“He’s got a shop – Millwoods”

“Really? I thought Millwoods was owned by Susan Mellordew’s faarther.”

He appeared not to believe me. Oh to have that conversation again knowing what I know now.

“Perhaps the Mellordews would like others to think that,” I should have said.

Grammar schools were set up to get people into university, or at least teacher training college. Everyone else was a failure to be eased into the grubby world of banking, accountancy or other forms of servility, unless you were a girl, in which case they didn’t really care either way because you would be married with kids in a few years’ time. I didn’t care either. I was quite taken by the idea of making a lot of money, especially as all six of my university choices had given me straight rejections.

At least the local accountants wanted me. They phoned my dad to change my mind about going off to a job in Leeds. “He’ll get just as good experience here,” they told him, but he decided not to pass the message on, as if they wanted me but he didn’t.

I had tried York first. The area training coordinator at The Red House sent me round to Peat, Marwick and Mitchell, one of the biggest and most powerful firms in the country (as KPMG they still are), to be interviewed by another stuck-up posh git whose laconic disinterest oozed the impression that he had indeed made a great deal of money. He would have got on just fine with my headmaster. Not for the last time did I feel I might have done better had I been to Bootham’s or Queen Ethelburga’s.* Real chip-on-the-shoulder stuff!

The Leeds firm were more down to earth. Their offices were in what had once been a cloth warehouse with large airy windows; less depressing than the pokey accommodation of the other firms. A simple half-hour chat with one of the partners, during which I managed to avoid showing too much stupidity, and the job was mine: five years as an articled clerk. I started on the 9th September, 1968; exactly fifty years ago today.

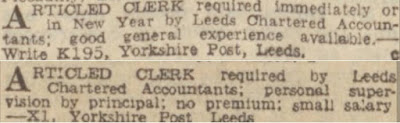

The thing is though, in those days, firms of accountants were desperate for articled clerks. At face value it was attractive: a form of indentured apprenticeship under which a qualified accountant undertakes to inculcate an articled clerk into the principles and practices of the profession. In reality it was cheap labour. They sold it to school leavers through discreet ads in the situations vacant columns, next to those for hair restorers and varicose veins. “Leaving school? Why not become a Chartered Accountant?” It would not have looked out of place if they had added: “No one need know; confidentiality guaranteed.”

Ads were discreet because accountants were not allowed to tout for business, although as things began to change, the bigger firms pushed the boundaries with larger, more flamboyant offerings designed by expensive agencies. One of the most memorable went: “Some think Wart Prouserhice is just as good as Horst Whiterpart, but we know it’s best at Price Waterhouse.”

Today, accountancy training places are so sought after they won’t even look at you unless you have at least a 2:1 and an impressive portfolio of extra-curricular leadership activities – an internship in the House of Commons; volunteering with Ebola victims in Africa; representing Great Britain in the Winter Olympics; that kind of thing. You might then get invited to a day of written tests and observed activities, and if successful to a nerve-racking interview panel. Those who went to Bootham’s or Queen Ethelburga’s might then be offered a place. Back in the nineteen-sixties, five ‘O’ levels and you were in.

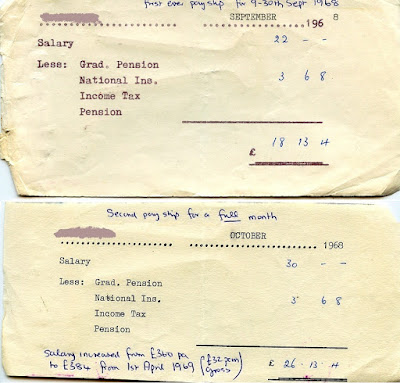

Not so many years beforehand, articled clerks had been expected to pay a premium for the privilege of the job. At least by 1968 you got a salary, if that’s what you could call it. Mine was £360 per annum.

Really? Well yes. Here are my first two pay slips. The first covers from the 9th to the 30th September, 1968, i.e. twenty-two thirtieths of a month. So 22/30 x 360/12 equals a straight £22, with a deduction of £3 6s 8d for National Insurance, leaving £18 13s 4d for my first three weeks’ pay. My first full month’s take-home pay was £26 13s 4d. I didn’t have to pay tax because I only started work in September, but I did after April when I got a £2 per month rise. It doesn’t look any better even when adjusted for inflation – £26 13s 4d in 1968 is the equivalent of around £400 today, less than half the minimum wage for an eighteen year-old.

I never did become a Chartered Accountant. I stuck it for a few years, failed a few exams, and then escaped to university. Would I have fared better in my parochial home town of canners, carriers, barbers, farmers, shippers and shopkeepers? I might have fitted in – like a pile of coke outside the gas works – but maybe not. Thirty years later, one lad from my class at school who did go to work with the local firm ended up as one of the senior partners in charge of the whole outfit. He did make a lot of money.

* Fee paying boarding schools near York.

Labels:

1960s,

accents and language,

accountancy,

dad,

Leeds,

school

Monday 19 March 2018

Review - Chris Bonington: Ascent

Chris Bonington

Ascent: a life spent climbing on the edge (3*)