It can be hard moving on your own to somewhere you don’t know anyone. Perhaps it’s not so bad when you are young, but I did it in my thirties. Things were fine at work, but home alone in the evenings, well, you don’t expect it to be like that.

I moved to the Midlands. I’d had enough of working in universities – that’s another story – and come to accept I was better on my own – also another story, a long and disagreeable one.

In universities, you think you are solving the world’s problems and work too much, but in this new job, when I went home, the time was mine. I looked around for things to do. I went to a couple of po-faced meetings of Friends of the Earth, but it was too much like work: sub-committees and working-group meetings. Then I saw an ad in the paper: IVC: ‘The Inter-Varsity Club’; it said something about “meeting people with similar interests” and “broadening your social life” with “concerts, meals out and other activities”. It met on Monday evenings in a scruffy room above a dingy pub. We carried our drinks up from the bar and mixed and chatted in small groups. It was full of eccentrics and misfits. I fitted in perfectly.

The IVC had started in London after the Second World War when a group of Cambridge undergraduates wondered how they might “replicate their busy university social lives through the summer vacations”. Whatever could they have meant? They organised dances for students, graduates, teachers, nurses and almost anyone else with nothing better to do, and soon added other activities such as walks and theatre trips. By the nineteen-eighties there were branches all over the country and the focus had shifted to year-round activities for young people who had moved to unfamiliar places. Some remained members for years, even into their forties and fifties. It was definitely a mixed-age group that I joined.

I have never had such an active social life. Some weeks I went out every night.

Activities were organised by members, with participation by sign-up. We went to films, plays and classical and pop concerts. We had meals out, days out and evening and weekend walks. Some events were in members’ homes, such as craft activities, coffee evenings, colour slide shows and parties. I went on a couple of long weekends away: walking in Exmoor and the Forest of Dean.

The walks were always popular: you tended to chat naturally with everyone else at some point along the route. I ‘hosted’ several myself, but also dragged people along to things like talks and poetry readings. One of ‘my’ events was a lecture about the Luddites by an almost eighty year-old Michael Foot. He shuffled on, steered by an assistant, wearing a shapeless cardigan buttoned out of alignment with a spare button hole at the top and a spare button at the bottom. Things looked distinctly unpromising until he began to speak, when he proceeded to mesmerize everyone in the theatre with a brilliant talk in the richest, most authoritative voice you could imagine.

Two twice-yearly events were especially well-anticipated: ceilidh dances and the ‘Galloping Gourmet’.

The Galloping Gourmet, a miracle of organisation, was a five-part meal (sherry, starter, main course, pudding and coffee) with courses in different homes. It worked like this:

To take part, you either (a) host sherry or coffee, (b) provide a course for six people, or (c) are a driver.

Each starter, main course and pudding is served to groups of six in five different homes at a time. Everyone starts in one of two locations for sherry. They move on in threes to somewhere else for starters, joining with three from the other sherry location to make six. The threes are then re-shuffled and move on to somewhere else for main courses, and again for puddings. Everyone ends up at the same place for coffee.

Thus, with 30 participants, there are 3 sherry/coffee hosts, 10 drivers, 15 course providers and 2 organisers who get a free ride. Instructions to drivers are prepared ready to be handed out by the hosts, e.g. “Please take Margaret and Jim to Margaret’s at 1 Sandy Street, Wibbleton, to arrive by 7.30 for your starter”, where the next instruction might be: “Please take Jim and Sue to Bill’s at 2 Rocky Road, Wobbleton, to arrive by 8.15 for your main course”.

Apart from one or two legendary mess-ups (such as the clueless chap who asked “what do we do now?” when he and five others arrived at his bedsit expecting a starter) it worked brilliantly.

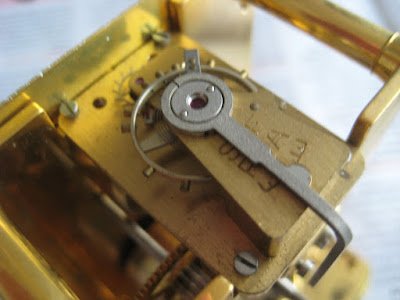

But you know what happens in clubs like IVC, don’t you? You find that those with similar interests attend the same things, and you make friends, and they ease into your thoughts and you begin to wonder what if you had a special friend. One, with laughing blue eyes and a liking for Bushmills whiskey, looked delighted when the clockwork of the ceilidh brought us together. I began to go to all her events and she to mine. The Galloping Gourmet organiser sent us to the same places most of the way round. One warm evening in peaceful Leicestershire ridge and furrow, where heron rise and kingfisher flash along the Kingston Brook, I offered a hand over a difficult stile. “What are men for,” she wondered, “if not to help you over difficult stiles?” Her hand lingered a little longer than necessary and I went kind of shivery and weak all over.

Herons and kingfishers bring luck, peace and love. After that, Dear Reader, we had a few private events of our own. We’ve been married now for thirty years.

It wasn’t all that long before I had another university job, too.