and C. P. Snow’s surprising digital footprint

(first posted 11th November, 2017)

My dad was captivated by ships from childhood, when ocean-going liners were the most exhilarating machines ever built. He knew the names and colours of the British shipping lines and some of the foreign ones too: Cunard: red and black funnel, yellow lion on a red flag; Union Castle: also red and black funnel, red cross on a white and blue flag; Peninsula and Oriental: buff yellow funnel, blue, white, red and yellow flag. It was partly why we found ourselves on holiday near Southampton, the first time we had ever been so far from Yorkshire. Once there, it was inevitable we would visit the docks.

As we approached Ocean Terminal, three towering Cunard funnels told us the Queen

Mary was in port. Small boat owners vied for passengers to take to see her sail: an opportunity not to be missed.

|

|

RMS Queen Mary arriving at and departing from Southampton for the last time in 1967

(two videos, approximately two minutes each - click to play) |

We boarded a launch and sped off down Southampton Water leaving the

Queen Mary at the quayside. Any doubts as to why we had sailed so far

ahead were soon answered. “The Mary’s moving,” our own captain

announced, and within a short time she had overtaken us as smoothly and effortlessly as a huge white

cloud in a strong breeze, a vast floating

palace towering above. Her powerful engines were easily capable of 28

knots (about 30 miles or 50 kilometres per hour) compared to our 6 or

7. We were left bobbing like corks in her wake as she turned into the

Solent. Dad remembered the day for the rest of his life.

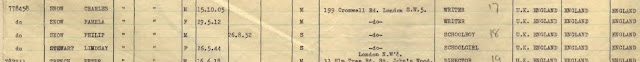

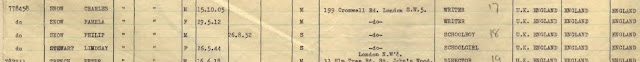

From photographs and postcards I can work out it was towards the end of August, 1960, during the last dying years of the transatlantic passenger trade. From genealogical web sites, I can pinpoint the precise date as Thursday 25th. The Queen Mary called briefly at Cherbourg before crossing the Atlantic to arrive in New York on Tuesday 30th, a five-day voyage. Not only that, but, incredibly, you can see the ship’s manifest listing the individual names and details of every one of the 1,024 passengers and 1,203 crew under the command of Commodore John W. Caunce. It is an incredible digital footprint.

Many of the first class passengers are googleable, among them two writers, Charles and Pamela Snow. They were the distinguished novelist and scientist C. P. Snow and his equally-accomplished wife, the novelist and playwright Pamela Hansford Johnson, travelling with their son Philip and her teenage daughter Lindsay Stewart. Philip was just one of eighty children on board. Some of them stood on deck and followed that incomprehensible human instinct to wave to strangers in the accompanying flotilla of pleasure boats. I wonder if any of them noticed a ten-year old boy waving back.

At the time, C. P. Snow was enjoying the controversy caused by his

Two Cultures lecture the previous year, in which he had lamented the gulf between science and the Arts which he, justifiably, believed he bridged. He had implied that many scientists would struggle to read a classic novel, and that many humanities professors would be unable to explain simple scientific concepts such as mass and acceleration, making them the scientific equivalent of illiterate. Most resented the insinuation that a poor knowledge of science rendered them uneducated and ignorant, including the acclaimed literary critic F. R. Leavis who let loose an astonishingly abusive and vitriolic response. Part of it went:

Snow is, of course, a – no, I can't say that; he isn't. Snow thinks of himself as a novelist [but] his incapacity as a novelist is … total: ... as a novelist he doesn't exist; he doesn't begin to exist. He can't be said to know what a novel is. The nonentity is apparent on every page of his fictions … Snow is utterly without a glimmer of what creative literature is … he is intellectually as undistinguished as it is possible to be.

Leavis continued the attack at length, giving examples of what he said was Snow’s characterless, unspeakable dialogue, his limited imaginative range, and his tendency to tell rather than show. Others jumped to Snow’s defence, suggesting it was in fact Leavis who could not write. It was brilliant, sensational stuff, still talked about decades later. Both academia and the general public, including my dad, soaked up the spectacle in pitiless delight, entertained by intellectual heavyweights slugging it out with metaphorical bare knuckles.

None of this meant anything to me at the time, of course. It would be another twenty years before I discovered and found it greatly entertaining, but my dad would have been fascinated to learn that Snow and his wife were on board. A little more googling reveals they were on their way to spend the autumn at the University of California at Berkeley. Before their return, both, along with the prominent English writer Aldous Huxley and the American Nobel chemist Harold C. Urey, took part in seminars on

Human Values and the Scientific Revolution at the University of California Los Angeles on the 18th and 19th of December. The Staff Bulletin described it as “one of the most distinguished intellectual occasions in the history of the University of California”.

If it is possible discover this much about the activities of (albeit well-known) individuals in 1960, one fears to imagine what digital footprints we might leave behind ourselves. Much of what we buy, our social interactions, our medical and educational records, our motoring activities, and so much more, are now all stored on a computer somewhere, possibly in perpetuity. I wonder who is going to be looking at mine in sixty years time.