“You’ll be all right one day son,” his own father had told him in expectation of a life-changing legacy due on the death of an ailing wealthy spinster living permanently in a hotel in Harrogate. As things turned out she lived another thirty years, by which time the legacy was no longer life-changing, much of it having dwindled away in unnecessary professional fees.

|

| Edwin Ernest Atkinson (1872-1939) |

On leaving school, Edwin had first worked as a clerk for the Aire and Calder Navigation Company at Goole docks, and then as a coal exporter with the shipping company J. H. Wetherall & Co. In 1906 he began in business on his own, joined in 1911 by Thomas William Prickett.

Within twenty-five years both were rich men with handsome houses on the outskirts of Hull at Hessle. Edwin’s was called ‘Waylands’, at the corner of Woodfield Lane and Ferriby Road. It had eight bedrooms, an oak-panelled dining room, two other large reception rooms, a billiards room, domestic quarters, coal-fired central heating, outbuildings, cultivated gardens, a heated greenhouse and vinery, tennis courts and a croquet lawn. Thomas William Prickett had a similar property, ‘Northcote’, next-door-but-three at 85 Ferriby Road. Among their ships – their dirty British coasters with salt-caked smoke stacks – were the SS Yokefleet, SS Swandale, SS Easingwold and MV Coxwold. There were trains of railway wagons bearing the company name.

|

| 'Waylands', 93 Ferriby Road, Hessle (now 'Woodlands Lodge') |

|

| Atkinson and Prickett ships: SS Yokefleet, SS Swandale, SS Easingwold, MV Coxwold |

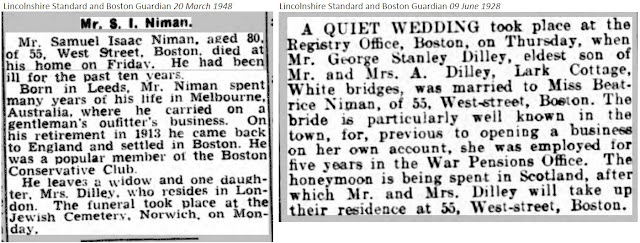

When Edwin died in 1939 at the age of 66, he left a life interest in most of his £27,000 estate to his wife and only surviving daughter. Adjusted for retail price inflation, this would be today’s equivalent of £1.3 million; probably five times that in terms of earnings inflation, and far more in terms of property prices. It was a considerable sum of money. His wife died less than two years later, thus his daughter, Constance Ruby, still in her thirties, assumed a life interest in the whole sum, to live in comfort and luxury for the rest of her life. She was the lady in the hotel at Harrogate.

Note that Edwin only left a life interest to his wife and daughter, rather than the capital sum outright. They therefore received income from investments, and the capital remained intact. It was perhaps a throwback to those earlier chauvinistic times when women were not expected to manage their own financial affairs. It also kept the money out of the hands of any unscrupulous husbands they might later marry.

|

| Numbers 8 to 2 North Bar Without, Beverley, with the fifteenth century gate to the right |

Constance Ruby never did marry, although she did have a brief engagement at the age of twenty. She later became Clerk to the Archdeacon of York, living in the Precentor’s Court at York Minster. After her father died she moved to Harrogate with her widowed mother. Later in the nineteen-fifties, she moved to Beverley, into a half-timbered eighteenth century house immediately without the North Bar (the fifteenth century gate). She died there in 1983. As she was the last surviving descendant of Edwin Ernest Atkinson, the capital passed in equal shares to the families of his three siblings. One of them was my great-grandfather’s second wife.

Five years after his first wife had died, my great-grandfather had married Edwin’s sister, a forty-eight year old spinster. There were no further children, but a deeply shared interest in Methodism saw them happily through the next twenty-four years. Of course, they and Edwin’s other siblings had all died long before Constance Ruby in 1983, so the money passed to their families. Thus, one third of the capital passed by marriage, through my great-grandfather, through his children who had also died, to my father, his sister and their late cousin’s husband – people Edwin probably never heard of.

It was not so simple. An unfortunate legal charade had gobbled up much of the inheritance. The solicitor who managed the capital trust had sensibly taken steps to establish the names of the beneficiaries in readiness for when the trust was eventually wound up. He had collected the documentation to show that my father, his sister and their cousin were the rightful beneficiaries to a one-third share. But then, at some point during the nineteen-seventies, the National Westminster Bank trustees department persuaded Constance Ruby that her affairs would be better handled by them, and took over the management of the trust. They began the lengthy process of establishing the beneficiaries all over again, but after several years were still not convinced they had identified them all. Everything came to a standstill after Constance Ruby’s death. It was only through our persistent intervention that the case was transferred back to the original solicitors and at last sorted out.

Around this time, bank Executor and Trustee departments were becoming known for their outrageous fees. An article in The Times in 1985 explained how one executor saved nearly £7,000 by handling a simple £100,000 estate himself. Solicitors charged less, but were still expensive. We have no way of knowing what fees were taken out of the Atkinson trust, how well the investments performed, or how much income was paid out over the years, but when my father and his sister at last received their legacies, what would once have been life-changing sums had shrunk away to just over £3,000 each. Their cousin’s husband (i.e. Edwin’s sister’s husband’s granddaughter’s widowed husband) got £6,000. Welcome amounts for sure, but nothing like what my grandfather had predicted. £3,000 might have bought a small car. The total value distributed to all beneficiaries would have been around £37,000. Had the capital kept pace with retail price inflation it would have been at least ten times that amount.

In later years, when my father made his will, true to his principle he appointed me as executor. After he died I handled everything myself. It was fairly straightforward. In another case I was able to manage sums in trust for children until they reached the age of eighteen. More recently, I handled all the paperwork for the estate of another family member. Despite being complicated by inheritance tax (by then inevitable for owners of houses in the Home Counties) it was still trouble free. Estate administration can be a long-drawn-out and time-consuming process which tests your patience and endurance, but if you have the time to cut out the banks and solicitors and do things yourself you can save an awful lot in professional fees; often several tens of thousands of pounds. You can bring things to completion much more quickly too.

References:

Maggie Drummond (1985). Finding a will and a way to cut costs. The Times (London, England), Feb 16, 1985; pg 16.

Patrick Collinson (2013). Probate: avoid a final rip-off when sorting out your loved one’s estate. The Guardian, Sep 21, 2013.