This ‘memoir’ started as a kind of autobiographical attempt to understand how things changed during my time and how I got to where I am, a record for posterity in the forlorn and vainglorious misbelief that someone might one day be interested. I hope it is not too tedious to return to this idea now and again.

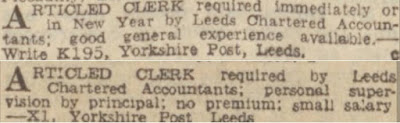

One thing I wonder about is how I fell into such an agreeable career in computing and universities after badly messing up three previous chances: failed ‘A’ levels, abandoned accountancy training and student teacher dropout. Fortunately, for post-war baby boomers, chopping and changing was easier than for any other generation before or since.

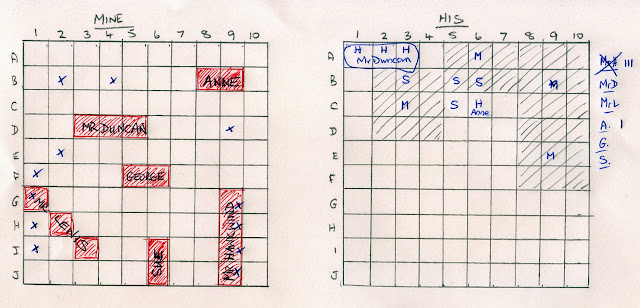

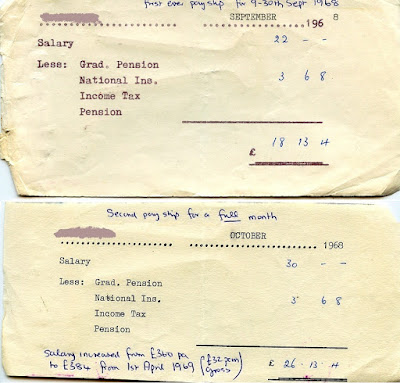

At twenty-four I was in a run-down shared house and ordinary office job, a lowly clerk with a Leeds clothing manufacturer. It was pleasant enough: home at five, no exams, no correspondence courses, no expectations. It was the largest clothing factory in Europe: cheap suits, nice canteen, warm sausage rolls on the tea break trolley and three hours in the pub every Friday afternoon. You could idle your whole life away. One lad just four years older had already done fourteen years. Real old-timers still talked fondly of Sir Montague, the firm’s founder, and crossed off their days to retirement on the calendar.

With my record what else could I do? Backtrack? Repeat the same things? They said to take the Cost and Management Accountants exams but I barely went through the motions. Eighteen months drifted by. Yet in that time I made progress – seemingly by doing nothing much at all.

Along the road was the tranquil lunchtime retreat of the Compton Road Library, an L-shaped building on the corner with Harehills Lane: the adult library in one wing, the children’s in the other, always warm, always silent, a pervading smell of floor polish throughout. Like all libraries then, they still used the 1895 Browne Issue System: the Pinterest photograph shows the catalogue drawers and tray of readers’ tickets holding cards from books out on loan.

It seemed far more extensive than the picture shows. I got through three or four books a week. It felt like a displacement activity but some left quite an impression. What did I read all that time ago?

There were walking and mountaineering books. Chris Bonington’s

I Chose to Climb and

The Next Horizon really caught my imagination. I acted them out on walks, scrambled up mountains, bought a Minivan, grew a beard and tried to write things. I took W. A. Poucher’s

The Scottish Peaks, a treasure trove of routes and photographs, to Glen Brittle in Skye in the Minivan door pocket and got it soaked. It looked so awful I daren’t take it back, so said I’d lost it and had to pay £1. I’ve still got its stained and curly pages.

There were biographies and autobiographies. I dreamt of escaping like a hermit to some isolated part of Scotland, like Gavin Maxwell in

Ring of Bright Water. I tried to emulate R. F. Delderfield who mentions in

For My Own Amusement that as a young writer he had been advised to write character sketches of people he knew: “mental photography” he called it. I wondered what it might be like in a garret in Paris struggling to be a writer like V. S. Pritchett in

Midnight Oil, “a free man in Paris, unfettered and alive,” as Joni Mitchell put it.

I was unimpressed by Jonathan Aitken’s

The Young Meteors in which he interviewed over two hundred leading lights of pop music, film, television, art, photography, clothing, design, politics and business from nineteen-sixties ‘swinging’ London. Some were truly talented but many had either known the right people or just been lucky.

There was fiction: A. J. Cronin, O. Henry and more – anything so long as it was not accountancy.

And all the time I was asking “could I do that?”, “could I be like this?”, “could I write like that?”

We reach a point in our lives where we need to construct an identity for ourselves: to decide who we would like to be and who not. Some manage it as teenagers, others later and a few possibly never. Some get there gradually, others in leaps and bounds. It might take no conscience effort or be a tortured, soul-searching experience. It can take several attempts. For me, it was definitely late, bounding and tortured with false starts.

“It’s a good career, accountancy. Stick at it. You’ll be all right once you’re qualified,” they said, but I was reading about people who had made their own way.

I was never going to chuck everything in for a Parisian garret or Scottish hermitage, but back came the idea of becoming a mature student: at university, not a return to Teacher Training College. The only way would be to take ‘A’ Levels again, a daunting prospect. I approached temp agencies to work flexibly while resitting them, and handed in my notice.

“Don’t cock it up again,” said one of the few supportive friends I had left, mock anguish on his face as he imagined the consequences.

“Course not,” I said with pretend confidence, not too sure.

One thing I am sure of though. A decade or so earlier there would have been no chance. In all likelihood, it would have been national service, back to where I came from, a mundane job and family responsibilities sooner rather than later. Ties. Restrictions. Few opportunities. I doubt I would get as many breaks now, either.