|

| The Basil Brush Show |

Google Analytics

Monday, 15 December 2025

I Don’t Mind If I Do, HUH!

Monday, 8 December 2025

Disturbingly Different Outcomes

It was a music friend’s funeral recently. He died of lung cancer. There was much in common with my own situation.

He was very fit, and in early autumn was walking in mountains in Scotland. He retired a year ago from his job as head of English in a secondary school in the Sheffield area, and had just started the second year of a Masters course in Creative Writing. But there the similarities end.

In October, he noticed a slight shortness of breath when walking up hill and playing his flute. The doctor sent him for an urgent scan (unavailable to me during covid lockdown), and he was diagnosed with lung cancer. An early thought was to offer help with questions from our own personal experiences, seeing that is what I also have, and have had a wide range of tests and treatments. However, a day or two later, we heard he was in hospital after a stroke, and may then have had more. He died fifteen days after diagnosis. Fifteen days! He was 64.

And I’m still here after three and a half years, struggling, but still here and hoping, with luck, to see 2026.

His cancer was in the plural membrane, not one of the lobes.

Wednesday, 3 December 2025

That’s Oldies

I have been watching UK TV Freeview Channel 840, “That’s Oldies”, which I came across by chance, and had a 1960s music fix. It shows old TV rock and pop music from the 1950, 1960s, and 1970s, non-stop, end-to-end all day. These are not the tired old “Top Of The Pops” BBC programmed, endlessly repeated.

Watching again now, there are groups I enjoyed enormously, such as Cream and the Animals, and others, at least for me, completely forgotten, such as Thunderclap Newman.

They seem to play chunks of 1960s British groups, 1970s, and 1950s with American music. Most except for the 1970s are in black and white. Much of the 1950s music is from American television shows, but not the original hits.

Needless to say, I enjoyed the 1960s groups most. Many you might expect to see do not feature. There is nothing of The Beatles, Rolling Stones, or The Who. I guess it is a rights issue. So, what you get are rarely-played groups with their lesser-known hits that did not reach the top 3. That’s all right. I have not seen most of them for 60 or 70 years, and found them fascinating.

What strikes me now is how good they were, and how many new things I missed in them at the time, such as harmonies, counter melodies, and clever solos. There were so many groups I dismissed as not worthy of attention, probably because I have much more musical knowledge and appreciation now, and, hopefully, am a better guitarist.

It is also surprising how well groomed they all were. They were thought scruffy, but most are wearing suits.

Monday, 1 December 2025

The Commercialisation of Universities

Two items in the recent press about Higher Education:

1. Universities are awarding too many first class degrees. The think-tank Reform argues that universities risk losing their credibility due to “rocketing grade inflation”. Apparently, 26% of U.K. students now get first-class degrees and one university awards them to over 40% of students. Similarly the proportion of 2:1 degrees, nationally, is now nearly 50%. The think-tank suggests the number of first-class degrees should be capped at 10%, 2:1 and 2:2 degrees at 40% each, with the lowest 10% getting a third. (Guardian; BBC).

2. Universities are making too many unconditional offers. Ucas reports that a third of 18-year-old university applicants received some form of unconditional offer last year, made up of true unconditional offers, and conditional offers which became unconditional when an applicant makes that university a firm choice. Some institutions are also offering students four-figure bursaries. (Guardian).

The reports highlight massive increases in the numbers: a doubling of high grades over ten years, and an almost thirty-fold increase in unconditional offers over five years.

Well, when I graduated in 1980, out of the 70 people who started the course, just 2 got firsts, less than 3%, and that was an exceptional year. Some years there weren’t any. And it was completely unknown for universities to make unconditional offers to 18-year-olds yet to take their ‘A’ levels; it might not even have been allowed.

Isn’t it simply a case of commercial organisations providing the service their customers want? In almost any other sector it would be singled out for praise. Perhaps if universities had not been turned into competing businesses in the first place, these things would not be happening.

Friday, 28 November 2025

Quick Health Update

Struggling with responding and commenting. Need another course of steroids, which should sort it out in a few days.

Monday, 24 November 2025

The Hillman Is Waiting

A third post about the Automobile Association. The first two are here and here.

Detailed route maps were another service offered by the AA. You can still get them online, but in the 1960s they came in paper booklets setting out your route from beginning to end, junction-by-junction. This old example was on the internet.

From around 1960, we began to hire cars for holidays. We went all over the country: Barmouth in Wales, Edinburgh and Aberdeen, Cromer in Norfolk, Kent, Devon. Finding your way was not then straightforward. It was before motorways, and you had to go through several large city centres. We always sent for an AA route map. Mum sat in the front seat turning the pages and reading the directions out loud. Sooner or later it ended up in confusion.

In 1960, we headed for Christchurch, Dorset. “Where’s that?” Grandpa asked. “Near Southampton,” Dad told him. “You’ll never get there, son,” he said. He was almost right. We got hopelessly lost going round in circles in Leicester, despite the route map. “You are one of many,” said a bemused man sitting on his front garden wall watching the traffic.

The hire cars were always Hillmans from Glews Garage, then a Rootes Group dealer. The Hillman Minx was a lovely car, respectable and middle class. Dad liked them because they are mentioned in a poem by John Betjeman, which tells of a lifestyle we could never even hope to aspire to: “The Hillman is waiting, the light’s in the hall, The pictures of Egypt are bright on the wall”. But we could have a Hillman.

So, it was no surprise when, in 1963, Dad collected a Hillman Super Minx from Glews as usual. I noticed almost straight away that it was brand new, but he did not let on immediately we had bought it. Mum had one of the biggest shocks of her life.

I can’t work out where we went for that first trip; I think it was south. A few days later, I noticed one of the pedals was wet, and it turned out to be leaking clutch fluid. Directed by the AA Handbook, we soon found the nearest Rootes Group dealer who carried out a temporary repair until the master cylinder could be replaced at home

Later that year we went to Aberdeen, and the following year to Inverness and Loch Ness. Here it the Super Minx (the blue one) at Jedburgh on the way to Scotland in 1964. Next to it is an earlier model, an ordinary Hillman Minx.

Dad was incredibly trusting with that car. When, a few years later, I learnt to drive, be let me borrow it on Saturdays for trips with friends to places such as Leeds and York. I will now admit to driving rather fast sometimes, but I never so much as even scratched it, although once or twice it was close. Perhaps he hoped I would so he could have a new one. It was becoming a bit of a rust bucket by then.

Cars did not last long in those days, but the Hillman Avenger that later replaced it seemed cheap and tinny in comparison. The chap who bought the Super Minx kept it going for another 5 or 6 years. Dad gave up on Hillmans after that, and his next cars were a Triumph and a Morris. The Rootes Group was bought by Peugeot Talbot, and I stupidly bought a Samba, the worst car I ever had.

Sunday, 16 November 2025

Peter Hitchens

I am always interested to read what Peter Hitchens has to say in the Mail On Sunday each week. It is supposed to be a pay-to-read column, but because of having to read using text-to-speech, I came upon a way to see it online for free by chance.

He tends to be seen as someone with views very much to the political right, but actually he is more of a contrarian. Certainly, he is no supporter of the Labour Party, but he is no fan of the Conservatives either, because, he says, they are not conservative. They do not conserve anything and have not done so for 45 years. Indeed, he blames Margaret Thatcher for much of the deterioration in modern Britain as we know it today.

Thatcher, for example, had the idea of privatising the railways and water companies, both terrible disasters, although carried out later. She removed the sensible old pub licencing laws, creating the drunkenness and violence that blights every city centre every weekend, with bouncers on every pub door for the trouble they know is coming, and the mess and expense of cleaning it up. She allowed the licencing of no-win no-fee lawyers, creating exaggerated health and safety panics that shut down trains and parks, and cost us all dearly in enquiries and speculative legal actions. She failed to save the grammar schools which did so much for equality of opportunity, and tried to cut the navy, and would have been unable to defend the Falklands. These were not conservative acts.

He has many opinions I disagree with, but at least unlike many of the moaning minions on Blogland, they are well informed and well argued. I think that essentially he liked the Britain he grew up in, and regrets the changes that have taken place. With a number of caveats, he is not alone in that. Unfortunately, he can come across as rather arrogant.

He has two long standing causes I am completely persuaded by, that he has been writing repeatedly about for years.

One is the harm caused by cannabis. It is fashionable to call for its legalisation, and argue that it is harmless, but, actually, it causes a great deal of damage to society and its users. Long term use reduces the ability to care about anything. It takes away motivation.

Nearly all the so-called terrorist attacks and mass stabbings and shootings are extreme cases. The evidence is over whelming, but it is ignored. Only now may a few psychiatrists and police be beginning to wake up to the problems. The Nottingham and Southport murders, and the recent train attack in Huntington, all have the stink of cannabis. They were not the result of terrorism. They are the actions of drug crazed nutters.

The second cause is that of Lucy Letby. She was found guilty of murdering very ill new-born babies in the hospital where she worked, and has been sentenced to spend the rest of her life in prison, but increasing numbers of expert doctors and legal experts are beginning to believe that a massive miscarriage of justice has taken place. The evidence simply does not support her guilt. Indeed, there is no clear evidence that a crime of any kind has taken place at all. It seems that the police and the hospitals decided she was guilty and then looked for reasons to support it. It is beyond appalling that this could happen to someone under British justice today, where there is supposed to be the presumption of innocence unless proved guilty. It could be you or me. Calls for a retrial have so far been dismissed.

Monday, 10 November 2025

Airmyn and Rawcliffe Hill

This is not so much about railways, but about an area I knew well which a railway ran through.

I was on the Rawcliffe bus with my mother, looking across the fields at a nearby metal bridge. It was a bright, sunny day, long before I started school. She would not yet have been 30.

“Is that Boothferry Bridge?” I asked.

“No, that’s the railway bridge.”

A few minutes later I asked again.

“Is that Boothferry Bridge?”

“No, that’s the railway bridge.”

I asked three or four times. A woman in the seat opposite looked at us and smiled.

The bridge carried the Goole to Selby railway line across the River Aire near Rawcliffe. It was a similar structure to Boothferry Bridge, but that is a road bridge across the River Ouse a couple of miles downstream. I had probably just learnt its name.

On 21st May, I included this evocative picture of a rather ancient train arriving at Goole around 1960. More recently, I mentioned the Flanders and Swann song “The Slow Train”, which contains the line “No one departs and no one arrives, From Selby to Goole, from St. Erth to St. Ives.”

It turns out that the train pictured is the very same Selby to Goole train. It travelled back and forth between the two towns for much of the day, and was sometimes called “the Goole and Selby Push and Pull” because it ran tender-first in one direction, so did not need to turn round. You can find pictures of the same engine and coaches at the Selby end.

That railway holds some of my earliest memories. Although I travelled on the line only once, the bridge, the railway track, and the area nearby form a backdrop to my childhood. I passed often and always looked out for them.

My one trip on the line was when, still very young, Dad took me to see the powerful East Coast Main Line locomotives that then passed through Selby. I suspect he wanted to see them more than I did.

The Goole to Selby route was a single line track, about 10 miles long. I learnt the station names: Goole, Airmyn and Rawcliffe, Drax Hales, Barlow, and Selby. I remember being fascinated as Dad explained how the drivers had to possess a token to enter each section of track, and watching the tokens being handed over by the signalmen. Tokens were like large metal keys, with sturdy wire loops so they could be handed arm to arm, with minimal risk of drops. There was only one token for each length of track, which meant that successive trains had to travel in opposite directions. I think there were two sections of track, with a changeover point half way to allow trains to pass. The driver and signalman had to swap two tokens simultaneously without stopping, giving one and receiving one, not an easy procedure. When we went, trains were still steam hauled before diesel multiple units were brought in.

The line pretty much bisected Goole and Rawcliffe by Airmyn and Rawcliffe Hill, where the road ran over the railway. It was a local landmark, the countryside being so flat. I passed at least once a week.

I liked the big lorries that came over the hill through Rawcliffe from the West to call at the nearby Woodside Café. At times, there could be 20 from all over the country parked there. Even after the M62 was built, drivers made the short detour to call in.

Mum liked to walk to the adjacent Bluebell Wood from which it took its name, to see and pick the abundant bluebells. We did not know better then. I remember going on another warm sunny day, also pre-school, past the distinctive Glews Garage, and the row of houses known as White City that were built for returning war veterans.

Airmyn and Rawcliffe station was next to the hill. For a time, Dad had a customer who lived in one of the station cottages. I liked to sit and wait for him when he took me to Grandma’s. “What a fantastic place to live,” I thought. Around the same time, my mother’s sister and her husband rented a smallholding nearby across the main road. I liked visiting there too. They had cows and chickens.

This is Airmyn and Rawcliffe station in the early 1960s. The stations were all made of wood.

Working late one Friday night in a thunderstorm in the dark, Dad arrived home very shaken. He had pulled up in his van behind a car that had stalled half way up Airmyn and Rawcliffe Hill, and was immediately hit from behind by another van that had failed to stop in time. He eventually made it home with the rear of his van smashed in, its contents ruined, and a painful back. I think it was one of the reasons he decided to retire a year or two later.

Even after the railway closed completely, Airmyn and Rawcliffe Hill remained for many years, with a tricky bend in the middle and the empty track bed running underneath. I became quite skilled at drifting round the bend in my Mini Van without slowing down. Eventually, the road was levelled, but the local landmark remained beside the new section of road, still with a tricky bend, empty track bed, and silent and unused railway bridge across the fields.

The Goole to Selby Line had only a short life; in fact, it has now been closed longer than it existed. It opened in 1910 and closed in 1964 as part of the Beeching cuts. It never attracted the expected goods traffic, and passenger numbers were low.

This football special for Selby Town supporters travelling to a match against Goole during the 1950s was an exception. Those were the days when if you needed a longer train, you just got more coaches out of the carriage sidings.

Much of the track has now been taken over by the A645 from Goole to Drax and Selby, which uses the railway bridge, and cuts about 8 miles off the previous route via Rawcliffe and Snaith. All that remains of the site of Airmyn and Rawcliffe Hill is a roundabout. The station cottages are still there, but unrecognisable. Unless you know, you would never imagine there had ever been a station there or any railway at all. Glews Garage stood prominently just off the M62 for many years, with its name on the roof in large red lettering, but has now gone, and White City is no longer white. It is good to see the Woodside Café still in business beside the wood, but few lorries stop there now, and I suspect there are no more bluebells.

I still look for all of them, though.

Saturday, 1 November 2025

Agents Of Maths Destruction

Who needs brains any more except to ponder how computers and calculators have changed the way we do everyday calculations?

At one time we needed brains for long multiplication and long division, drummed into us at primary school from time immemorial. It is so long since I tried I’m not sure I can remember. Let’s try on the back of a proverbial envelope.

|

| Long multiplication and long division with numbers and with pre-decimal currency |

To do it you had to be able to add up, ‘take away’ and know your times tables – eight eights are sixty four, and so on – but just about everyone born before 1980 could do these things without having to think.

Those of us still older, born before say 1960, could multiply and divide pre-decimal currency – remember, twelve pence to the shilling, twenty shillings to the pound. You had to have grown up with this arcane system to understand it. Perhaps we should have kept it. It might have put foreigners off from wanting to come here and there would have been no need for Brexit. As the example reveals, even I struggle with the division.

|

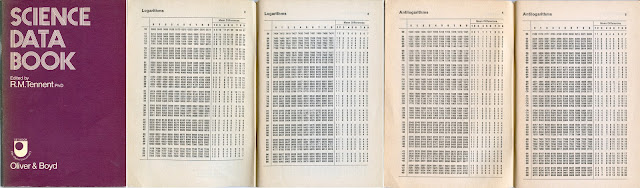

| Logarithms and Antilogarithms |

Then, there were logarithms and antilogarithms, as thrown at us in secondary school. To multiply or divide two numbers, you looked up their logs in a little book, added them to multiply, or subtracted to divide, and then converted the result back into the answer by looking it up in a table of antilogs. For example, using my dinky little Science Data Book, bought for 12p in 1973:

To multiply 2468 x 3579:

log 2468 = 3.3923; log 3579 = 3.5538; sum = 6.9461; antilog = 8,833,000

To divide 3579 by 24:

log 3579 = 3.5538; log 24 = 1.3802; subtraction = 2.1736; antilog 149.1

It’s absolute magic, although the real magicians were individuals like Napier and Briggs who invented it. How ever did they come up with the idea? It was not perfect. Log tables gave only approximate rounded answers and it was tricky handling numbers with different magnitudes of ten (represented by the 3., 6., 1. and 2. to the left of the decimal points), but it was very satisfying. You needed ‘A’ Level Maths to understand how they actually worked, but not to be able to use them. Some also learned to use a slide rule for these kinds of calculations – a mechanical version of logarithms – but as I never had to, I’ll skip that one.

|

| A Slide Rule |

Due to a hopeless lack of imagination, I left school to work for a firm of accountants in Leeds. Contrary to what you might think, our arithmetical skills were rarely stretched beyond adding up long columns of numbers. We whizzed through the totals in cash books and ledgers, and joked about adding up the telephone directory for practice. The silence of the office would be punctuated by cries of torment and elation: “oh pillocks!” as one desolate soul failed to match the totals they had produced moments earlier, or a tuneless outbreak of the 1812 Overture as another triumphantly agreed a ‘trial balance’ after four or five attempts.

| |

| A 1960s Sumlock Comptometer. |

But when it came to checking pages and pages of additions we had comptometer operators. Thousands of glamorous girls left school to train as Sumlock ‘comps’, learning how to twist and contort their fingers into impossible shapes and thump, thump, thump through thousands of additions in next to no time without ever looking at their machines. By using as many fingers as it took, they could enter all the digits of a number in a single press. It probably damaged their hands for life. I still don’t understand how they did it. There was both mystery and glamour in going out on audit with a comp.

|

| A 1950s Friden Electromechanical Calculator |

Back at the office we had an old Friden electro-mechanical calculating machine. What a beast that was. I never once saw it used for work, but we discovered that if you switched it on and pressed a particular key it would start counting rapidly upwards on its twenty-digit register.

“What if we left it on over the bank holiday weekend?” someone wondered one Friday. “What would it get to by Tuesday?”

Fortunately we didn’t try. It would probably have burst into flames and set fire to all the papers in the filing room. But we worked it out (sadly not with the Friden). It operated at eight cycles per second. So after one minute it would have counted to 480, after one hour to 28,800, and after one day to 691,200. So if we had started it at five o’clock on Friday, it would have got to 2,534,400 by nine o’clock on Tuesday morning. So, counting at eight per second gets you to just two and half million after three and a half days! It shows how big two and a half million actually is.

The obvious questions to us awstruck nerdy accountant types were then “what would it get to in a year?”– about two hundred and fifty million, and “how long would it take to fill all twenty numbers in the top register with nines?”– about thirty nine million million years. As the building was demolished in the nineteen eighties it would have been switched off long before then. But what would it have got to?

|

| An ANITA 1011 LS1 Desktop Calculator (c1971) |

The first fully electronic machine I saw was a late nineteen-sixties ANITA (“A New Inspiration To Accounting”), one of the first of many truly cringeworthy acronyms of the digital revolution) which looked basically like a comptometer with light tube numbers. Then, fairly quickly with advances in integrated circuits and chip technology, came the ANITA desk top calculator followed by pocket handhelds that could read HELLHOLE, GOB and BOOBIES upside down, and 7175 the right way up. Intelligence was as redundant as comptometer operators. We revelled so much in our mindless machine skills that I once saw a garage mechanic work out the then 10% VAT on my bill with a calculator, and get it wrong and undercharge me. It can still be quicker to do things mentally rather than use a calculator.

Around 1972, my dad saw one of the first pocket calculators for sale in Boots. It could add, subtract, multiply and divide, pretty much state of the art for the time, but at £32 (about £350 in today’s money) and not as compact as now, it required large pockets in more ways than one. I told him it was ridiculously overpriced. Infuriatingly, he ignored me and bought one. On the following Monday they reduced the price down to just £6. It was his turn to be annoyed but the store manager refused to give a refund. He stuck with that calculator for the next thirty years.

How often now do we even use calculators? Not a lot for basic arithmetic. Do we ever doubt the calculations on our computer generated energy bills and bank statements? Do we check the VAT on our online purchases? Do accountants ever question the sums on their Excel spreadsheets? Just think, a fraction of a penny here, another there, carefuly concealed, embezzlement by a million roundings, it could all add up to a nice little earner.

Sunday, 26 October 2025

Birthdays

Tuesday, 14 October 2025

Great-Great Grandma and Our Liddy

Monday, 6 October 2025

AA Assistance

In writing about the Automobile Association Handbook last month, I said the more you think about such artefacts, and the more other commenters contribute, the more you remember about them. The AA Handbook it a good case in point. I began to think about childhood memories of the AA, and later needing their assistance. It may be of interest only to me. I think there will be a third post, too.

I was aware of the AA from an early age. At that time, AA patrolmen still used motorbikes, with sidecars for their tools and equipment. One garaged and maintained his bright yellow bike in the back lane behind our primary school. As six year-olds we were fascinated. I am delighted to see the brick garage still there in the wall in the lane, now locked but recognisably the same. I thought about the children who walked with me to school, and what we talked about. How many still remember that 70 years ago an AA man lived there?

Until the 1950s, AA members were issued with metal radiator grill badges, and patrolmen would salute motorists displaying a visible badge. I have an early memory of being in a car and being saluted, but when and where I have no idea.

No salute meant a problem or hazard ahead. Apparently, this originated as a warning to members of police speed checks. Patrolmen could not be prosecuted for failing to salute. The practice would have ended in the late 1950s when motorcycles were superseded by small vans, which have gradually increased in size to the much larger vans now used.

The main role of AA patrolmen was then, as now, to rescue motorists whose cars had broken down. Members were issued with keys for AA phone boxes to summon help. These all seem to have gone now, presumably because mobile phones made them obsolete, but my key remains on the key ring.

I have needed help on three occasions. One was in the 1980s, on the A1 south from Scotland. The front end of the exhaust pipe broke loose from the engine, hacking and scraping along the road like an ancient tractor. The AA men tied it up and drove slowly ahead with me to Halfords. That Talbot Samba was new, my worst car ever.

Another occasion, around the same time, was somewhere on the M1 south when the exhaust pipe of the car in front fell off and bounced under mine. A little later, there was a smell of petrol. The fuel supply pipe was fractured, and an AA man mended it with a length of plastic pipe. It stayed in place until I sold the car.

But my first need was on Sunday, 1st September, 1974, on the M62 going home from Leeds, the day before I started a new job. It was also the day the new M62 opened from Whitley Bridge (J34) to Leeds. I was in my clapped-out blue Mini (the one in the blog banner), and after accelerating from the new slip road thinking how great it was, the engine cut out and would not restart. I coasted to an emergency telephone, but they were not yet operating. There was very little traffic, so I walked across to the other carriageway hoping to get a lift back to Whitley Bridge for help. Almost immediately, a police car came along. I thought I was going to be in real trouble, but actually the policemen were very helpful. They drove me back to the car and called the AA for me.

My most unusual experience with the AA was around 1972, again in the blue Mini, in Leeds. I stopped to give way at the junction of Royal Park Road and Queens Road in Headingley, and the front driver’s side wheel collapsed. At that time there was a scruffy garage across the road, run by the appropriately named Mr. Greasley (like a name out of Dickens), who took in my car with his trolley jack. Apparently, a wheel bearing had broken. Yes, he could mend it he said, and did.

Unfortunately, it began to make a noise within weeks. My usual garage said that a wheel spacer was missing. They repaired it again, but Mr. Greasley refused to refund me for his shoddy work. He asked for the broken parts, “in order to test them”, and lost his temper when asked for a receipt. After weeks of argument, I asked AA Legal Services for help, who obtained a full refund. It was not a lot of money, but to me at that time it was.

Our most recent encounter with the AA was my wife’s. She had an auxiliary steering wheel lock which broke at home in the locked position. As we had the Home Start service, we call the AA. It took the patrolman over an hour to remove it. It made you realise how effective these locks are.

Wednesday, 1 October 2025

Self-Doubt, Imposter Syndrome and Hegemonic Masculinity

New Month Old Post: first posted 26th January 2018

A couple of weeks ago, the normally impeccable Hadley Freeman, writing about self-doubt in her Guardian column [in 2018], said:“I have yet to meet a man who has worried he’s not good enough for a job he’s been offered, whereas I have yet to meet a woman who hasn’t.”

Well, I don’t know what circles she moves in, but that is simply wrong, as many of the responses to the online article make clear. Imposter syndrome is not just a female thing.

She finds it impossible to imagine a woman who, like certain men she amusingly identifies, is “perennially mediocre, untouchably arrogant, and eternally gifted by opportunity and protection by the establishment”. You only have to look at some of the women in high political office to see the error in this.

As regards men who worry they are not up to jobs they have been offered, there are lots, myself included. When I got good grades at ‘A’ Levels the second time round in my mid-twenties, and then a good degree, I felt that almost anyone could do it, and still do. When that led to jobs in universities, it felt like unmerited good fortune. When I got research papers into academic journals, I wondered why no one had seen the gaping holes they contained.

This is, of course, both blowing and sucking my own trumpet at the same time, but I just want to say that even for those who invented the concept*, hegemonic masculinity was never assumed to be universal.

* Connell and Messerschmidt.

The cartoon is from startupbros.com - click to link to its source.

Here is another relevant article from The Guardian.

Friday, 26 September 2025

Patties

|

| Tates Fish and Chip Shop in Rawcliffe High Street, 2000 |

“a staple option in most fish and chip shops in the East Riding of Yorkshire. I have never seen them for sale in Sheffield or Leeds. ... A patty is round - about 3.5 inches across and about 1.5 inches thick. It is made from mashed potato seasoned with sage and onion. Then it is dipped in a batter mixture before being deep-fried.”

For me, it raised a question. A bit more about Georgina Pocklington’s family history is needed to explain. You may remember I wrote in an earlier posts that she had eight children with three different fathers, among them my grandma’s half-sister, Aunty Bina.

Aunty Bina had ten children herself, i.e. my grandma’s half-cousins. She used to recite their names:

“... there was Aunty Bina who had Blanche, Tom, Gladys, Lena, Olga, Fred, Ena, Dolly, Albert and Jack. ... They had fish and chip shops all over.”

You could say they had a fish and chip dynasty. It was founded by Aunty Bina’s husband, Tom Tate. Later, their youngest son Jack (born 1919) took it over, and my mother and other relatives helped in the shop when called upon. It still bears its name in Rawcliffe High Street, pictured in 2000. It has quite recently been renovated with a new white UPCV door and shop window, and a new sign in similar style, and has lost all its character. I don’t know whether it remains in the family. Jack Tate was known far and wide for the size of his fish. He used a Swan Vestas match box as a template.

I visited Jack around 2000, when working out that part of our family history. It was a privilege to see him. There were many he turned down. He remembered my mother helping in the shop.

Many of Tom Tate’s children set up and helped each other open fish and chip shops themselves. So as well as Jack in Rawcliffe, there was one in Goole, one in Snaith, another in Retford, and, surprisingly, the eldest four children had shops in Rotherham. They were born in the 1890s, so had retired before 1970. We audited fish and chip shops when I worked in accountancy, and you could see what good businesses they could be.

[ADDED LATER] Tom Tate’s (junior) fish and chip shop in Rotherham is mentioned in Mike Marsh’s ‘Growing up in Goole, Volume 3’, although not by name. Mike Marsh was a childhood friend of Tom’s wife’s aunt, who arranged for them to stay with the Tates in Rotherham to see Donald Bradman and the Australian cricket team play Yorkshire at Sheffield in 1948. The Tates met them at Rotherham railway station, gave them unlimited fish and chips for tea, and took them to the theatre. After returning from Sheffield to Rotherham the following day, Brian’s “ever-generous uncle” bought them a real cricket bat and ball.

The ones in the Goole area certainly sold patties, but if there were once four fish and chip shops in Rotherham, with recipes originating in Rawcliffe, could you also once buy patties there, and can you still?

Monday, 22 September 2025

The AA Book

The Automobile Association Handbook, 1986-1987. I became a member when I bought my six-year-old blue mini in 1972. My dad joined around 1960.

The Handbook was originally annual, then twice-yearly, and from the 1990s undated. I have seen later editions, but the date is only in the small print. Like others, I kept mine in the car and threw the old one away when a new one came out. This one found its way to the bookcase.

It contained a wealth of useful information for motorists, such as tips on basic car maintenance, driving in winter, and road signs. It listed AA telephone numbers, recommended repairers, and hotels. It had road maps covering the whole country, and more detailed motorway maps showing all the junctions and service stations. You could get by pretty well without anything else unless you needed a larger-scale local map. I used mine to navigate all over Scotland and elsewhere.

It was always interesting to browse through the Gazetteer section, which gave details of every place in the country with a population above around 10,000. From this, we see that Goole in Yorkshire had a population of 17,127 (which would have excluded the local villages). Following Local Government reorganisation, it had moved from The West Riding of Yorkshire to become “the hub of Humberside”. It shows the telephone area dialling code as 0405 and the map grid reference. Markets were held on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays, and there was a cattle market on Mondays. Goole is 20 miles from Doncaster, 27 from Hull, 26 from Scunthorpe, and 23 from York. A very rare error shows London as only 18 miles away, when it probably should read 188. We can see that Goole had one AA recommended hotel, the Clifton, which is a 2* hotel, and that Glews Garage was an AA approved repairer, and also then a Vauxhall agent. I am sure that previous editions showed further information, such as early closing day which was Thursday, but this practice had probably been discontinued by 1986.

AA approved hotels were rated from one to five stars according to quality and services offered. 5* hotels, such as the Queens in central Leeds, were the best and most expensive.

For bigger places, the Gazetteer showed local maps, such as for Hull, which had a population of 268,302, three 3* hotels and one 2*. These city centre maps were good enough to find my way to meetings and interviews in Durham, Leicester, Nottingham, Huddersfield, Edinburgh, and even central Manchester.

The Handbook also showed road maps for the whole country. The example is East and West Yorkshire from Huddersfield to Hull (right click and open in new window to enlarge). By 1986, there were also junction-by-junction motorway maps. The example shows the corresponding part of the M62. Before the 1970s, there were few motorways in this region. I remember driving across the Pennines on the Western M62 for the first time, around 1973, and being awestruck by the astonishing grandeur.

Again, I think the Handbook once included details discontinued by 1986. I seem to remember lists of vehicle registration plates. For example, vehicles ending WW or WY would have first been registered in the eastern part of West Yorkshire. But one detail still included is the mileage chart, which is something else I loved to ponder. It gives the distance from Aberdeen to Hull by road as 361 miles, and from Inverness to Penzance as 723.

There have been many changes since the handbook was published. Among them, many of the named hotels have gone, Goole does not hold cattle markets, and Glews Garage no longer stands proudly with its name in iconic huge letters on the roof beside the M62. Goole, traditionally in the West Riding of Yorkshire, and then moved to the ridiculous Humberside, is now in East Yorkshire, even though historically in the West Riding. However, the motorway goes no nearer to Hull, despite considerable road improvements since I started driving.

As with so many of these artefacts, they set off unexpected chains of thought not considered for years, but rather than create an overly-long post, I will save them for another.

Monday, 15 September 2025

Uncle Owen

Last week, a man called Geoff came for a chat. He is a little older than me, and we had never previously met, but we have a kind of family link through my late Uncle Owen.

Owen was my mother’s brother. He appears in my recent post showing the picture taken at the seaside around 1936, which mentions that he died in a military accident in his early twenties, while on National Service.

One of many sad aspects is that he need not have been there. He was bamboozled into signing up for three years instead of the minimum two because, they said, it would be “good for his trade”. It was during the additional three years that he died. He was a plumber, and had just one year of his apprenticeship left to complete. He would nearly have finished but for that extra year. A plumber in the 1950s: what a lucrative trade that would have been!

He was in the Air Force, and was hit by an aircraft shell that went off accidentally and exploded in the chest and abdomen. He stood no chance. Many years later, my father told me the injuries were so horrific, the coffin was sealed, and the only part of the body allowed to be seen was the head and face through a hatched window in the coffin lid. The funeral procession stretched beyond the end of the village High Street, and there was a military guard of honour and salute. I was only 3 at the time, but when older, I used to help my grandpa tend the grave. Last time I looked, the small gravestone was broken and collapsed.

I can just remember him. He was well-known and popular, sang in the church choir (I have his prayer book), and played in the village cricket team. He had been married for 15 months to Aunty R. My grandparents had to intercept her as she returned home to Rawcliffe from work on the bus, to tell her about the awful telegram they had received.

I liked Aunty R enormously. She was always smiling. She was a skilled invisible mender at the clothing factory. She and Owen had grown up next-door-but-two to each other, childhood sweethearts. They spent their wedding night at our house, while we stayed with my grandparents.

One of the saddest photographs I have is of Aunty R with family members and friends three months after Owen died. She is in the centre of this picture wearing what we would then have called a costume (she is replaced by my mother in the second version). She puts on a brave face, but there is pain and sadness in her eyes. I am also in the picture, still aged under 4. Later, she came with us on holiday to Filey, and my grandparents took her with them to stay with friends in Scotland.

Aunty R remarried some years later, and moved to Huddersfield, near where we now live. I knew where she was, but did not want to revisit it while her husband was alive. About 5 years ago, after she was widowed a second time, I sent her some photographs, and she was very pleased to see them, and speak on the phone. She was then a surprisingly active 90-year-old, but died 2 years ago after falling.

To return to Geoff, my visitor: he married Aunty R’s much younger sister. They also lived in the Huddersfield area, but I was not sure where. When I discovered it was only within two miles of me, R’s sister by then had early-onset dementia, and Geoff had cared for her full-time for many years. She died over a year ago. My last memory of her is of a little girl, about 3 years older than me, sitting in the sun on the front doorstep with her mother, eating a packet of potato crisps. There were over 6 blue wraps of salt in the bag.

Geoff and I had an immediate rapport, with so many shared references and experiences, it was as if we had always known each other. We knew the same people who lived in the High Street where I spent every Saturday, and he was at school with my mother’s second cousin who helped me work out that part of our family tree. He could talk about the village social life, and who was related to whom.

It wa’n’t long afoo-ere we’wer’ in West Riding Rawcliffe talk.

I mentioned Uncle Owen was a plumber, and that I remembered him and my grandpa building an outside lavatory in the back yard. Before that, I said, they had an earth closet and an ash midden. You shovelled the lavatory contents through to the ash midden, a brick building with no roof, to be burnt with the household rubbish. Periodically, council workers shovelled the ash midden contents into bins by hand, and carried it to a lorry. He knew exactly what I was talking about.

“If you don’t pay attention at school”, my mother used to say, “you’ll end up working on t’shit carts”.

That really got Geoff going: things I’ve mentioned before. “It was so primitive,” he said. “Boiler on first thing Monday morning heating water, then all day washing with a dolly tub and peggy stick, and wringing it out with a hand wringer. Then using the leftover hot water to fill the tin bath, which hung in the yard for the rest of the week, and taking turns in the bath with the same water. Tuesdays were spent drying the heavy wet washing with wooden clothes props over a washing line, and Wednesdays ironing. Unbelievable!” he said. “It was little more than 60 years ago, yet when you tell ’em about the shit carts, they think you are talking about the dark ages.”

He knows I am ill and cannot easily get out now, but said he would like to call again. It would be good if he did.

As for Uncle Owen, he should have been busy installing indoor upstairs bathrooms, kitchen plumbing, and central heating systems. He could have had his own business, and his younger brother could have served an apprenticeship with him. Who knows, I might even have been a plumber myself. I would have had more cousins, and everything would have been different.

Monday, 8 September 2025

Pen And Ink

Monday, 1 September 2025

Ontogeny Recapitulates Phylogeny

New month old post: first posted 1st October, 2018

|

| Haeckel’s 1874 drawing of stages of development in the embryos of fish, salamander, turtle, chick, pig, calf, rabbit and human. |

Professor Clarke glowed with assured elegance. It was not only the beauty of his layout and lettering, it was his whole demeanour. With just the right proportion of wrist and cuff beyond suit sleeve, he grasped the chalk delicately between forefinger and thumb, and proceeded through the lecture with scholarly sophistication. What a privilege to be taught by someone whose work was so well-known and highly regarded throughout the world. We were rather in awe of him.

He was talking about pre-natal and neo-natal human development: physical and mental growth before and around birth. He concluded with a short quotation. None of us quite caught it, but we felt too stupid to ask. He said something like: “Antigen capital file genre.”

In those days, students weren’t given all the slides and notes on the internet to learn and parrot back in examinations. We used to read around lectures. We went to the library and made notes from text books and academic journals. We even owned quite a lot of expensive text books ourselves. So before long I worked out that what he had actually said was: “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.” Furthermore, I understood what it meant: a chunk of lecture succinctly summarised in three words.

The point is, as became clear when we later learned about how we acquire the power of speech and language, if we don’t understand something, if we cannot make sense of how the words fit together, we find it difficult to say. Think of the novelty song Mairzy dotes and dozy dotes and liddle lamzy divey.

Twenty-five years later, the children were laughing.

“I bet you can’t say “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppercorns,” said my wife, and recited the full verse, faultlessly. She followed it with “She sells sea shells …” as an encore.

“The British soldiers’ shoulders,” I added, not to be outdone. “The Leith police dismisseth us,” and then out of nowhere, “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.”

Within a few days, our eight-year-old son had got it. “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” he would tell anyone who would listen. At school, he was in Mr. Price’s class.

“Hello Mr. Price,” he said. “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny.”

“Aunty Jenny was late for what?” queried Mr. Price.

“It means when a baby grows in its mummy’s tummy, it starts off like a little tadpole, and then looks like a little frog, and then like a little bird, and then a little horse, and then a little monkey, and then a little baby.”

That guy is now a solicitor.

What a pity that Meckel and Serres’ theory of embryological parallelism, perfectly encapsulated in Ernst Haeckel’s catchy phrase, illustrated by his somewhat dishonest drawing and so urbanely recapitulated by Professor Clarke, has been discredited as biological mythology.