New Month Old Post: first posted 19th April, 2019.

My generation was not as open with our parents as our children are with us, at least not in my part of the North of England, or maybe it was just me. I never told my parents I went in pubs. Not even when old enough. The police told them. It was Easter Sunday, 11th April, 1971.

It was the day after I had been with three friends to The Green Bottle in the curiously named Spawd Bone Lane, Knottingley. The pub was packed with noisy, holiday-weekend drinkers, and we took little notice of a short-haired man in a suit sitting alone at a table in the middle of the room until he asked us one by one to go over to have a few words with him. He was a detective investigating a vicious attack on an elderly lady the previous afternoon*, although we did not know that until later.

I can still remember some of what he asked – name, age, address, where I been between 4.30 and 6.30 the previous afternoon, and where I worked. I told him I was an accountants’ clerk with Goodwill and Ledger in Leeds, to which he said, “Oh! Do you know Mr. Black?” I said no, there was no Mr. Black where I worked, to which he replied that he worked at the Huddersfield office. It so happened that we did have an office in Huddersfield, and being naïve and trusting, thinking it a genuine question, I said I wasn’t sure but thought I might have seen that name on the letterheads, and that Mr. Black might be a partner at the Huddersfield office. It seemed to arouse the detective’s interest. I had never been grilled by the police before, and found it unsettling, although I tried hard not to show it.

The detective moved on to my friends, one of whom was in the middle of a Fine Art degree, with a contrary “art student” attitude, full of the deep and mysterious philosophies to which such beings are prone. He was going through a phase of answering questions with enigmatic answers, that’s if he could be bothered to answer at all. When approached on a train in the Midlands by a woman carrying out a travel survey, he told her he was on his way to Johannesburg. No matter who was asking, or how serious the situation, he took the same line. It was also the case, coincidentally, that he had the same surname as me, which drew the obvious follow-up from the detective.

“Oh! Are you related?”

“I suppose we must be.”

“What does that mean?”

“Are we not all related in some way?”

The detective was suspicious. Did he think I had given him a false name, that of my art student friend? We had a bit of a laugh about it afterwards.

When you consider the gravity of the situation, it was not really funny at all, but we were still at that stage of youthful innocence which takes little seriously. Without really being part of it, we liked to imagine we followed the trendy, counterculture of underground bands and magazines such as Oz which was about to face an obscenity trial. You don’t realise now when you see old clips of bands such as Black Sabbath, just how excitingly anti-establishment they seemed, even in name. The police were joked about: you would see “Screw the Pigs” scrawled in four-foot letters on garage doors. This pushing of the limits, I would now say, was only possible because England, on the whole, was a much safer and law-abiding place than it is today, which makes the attack on the old lady all the more shocking. And of course, we did not yet know the awful details of the incident.

The following day, being Easter Sunday, I was at home, going through the pointless motions of revising for my accountancy exams. Dad called me down to the front room where two more short-haired men in suits wanted to see me.

“These two gentlemen are police officers, and would like to ask you some questions.”

Being the sort of person who feels guilty even if not (you know, when the teacher asks who made that silly noise and you go red, terrified she thinks it was you, even though it was someone else), it really scared me. I had to explain about the pub in Knottingley and about being questioned, and the two detectives went off satisfied, but it felt very awkward.

And that’s how my parents found out I went in pubs, although, they probably knew already.

There is now no sign The Green Bottle ever existed. It closed for good and was boarded up by 2009, burnt out in 2010, demolished, and is now the site of a care home.

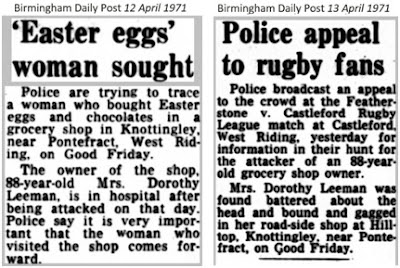

*From newspaper archives, I can see that the elderly lady

was 88 year-old Mrs. Dorothy Leeman. She had been beaten around the head,

bound, gagged and robbed of £80 on Good Friday in her roadside shop at

Hilltop, Knottingley, Yorkshire. She never properly recovered and died

less than six months later. It was an appalling attack and I don’t believe anyone was ever caught.

How well I remember the heady rush of liberality back in the early sixties. One almost wanted to be pulled over for speeding and taking the opportunity to offend the the officer because the supreme court had just declared it legal free speech to do so.

ReplyDeleteAn exciting idea, but at least in my case, if the opportunity had occurred, I would have been too afraid to go through with it and been the perfect example of politeness.

DeleteWhen I saw the title of this new blogpost, "A Visit From The Police", I immediately thought, "Oh what the hell has Tasker been up to now?" I imagined you being arrested for some sort of unsavoury behaviour. Imagine my surprise when I realised you were writing about happenings from over fifty years back in which you were not actually guilty of anything! It's hard to believe.

ReplyDeleteP.S. Rest in peace Mrs Leeman.

I've got away with everything so far.

DeleteWas that your only brush with the police, or are you a hardened criminal?

ReplyDeleteMy car was once stopped in a routine check and I had to take my documents to the police station later because I did not have them with me.

DeleteNo doubt one if not both of your parents smelt the demon drink on your breath. I think most people feel guilty if they are questioned by police, although perhaps not those who have actually done something wrong.

ReplyDeleteIt was more likely the cigarette smoke on clothes that gave it away. Pubs smelt awful in those days. I think the feeling guilty relates to conditioned attitudes to authority in those of my / our age, and perhaps not as prevalent now.

DeleteIt is a strange thing to think that 50 years after the fact there is someone walking around with that guilty secret. Poor old lady.

ReplyDeleteI suppose the attacker would have been a youngish person, so yes they could still be around, although someone like that would probably have committed other offences for which they were caught.

DeletePoor Mrs Leeman. For her to still work at her shop at the age of 88, and on what would be a bank holiday (in my country), she must have been desperate for even the smallest turnover. Those 80 pounds seem ridiculous now, especially in connection with such a vicious attack. (Of course 80 pounds were worth more in 1971 than they are now, I realise that.)

ReplyDeleteYour parents knew, I am sure. Parents nearly always know!

Equivalent to about £1,000 now. Small shopkeepers tended to be open all the time. At 88 it was likely to be more of a hobby for the social contact than essential for making a living. My mother could detect the smell of pub clothing from yards away.

DeleteSomehow I just knew you had a hidden, murky past.

ReplyDeleteDon't we all? I once pinched a pencil from work. There was also the time I drove over the speed limit.

DeleteJayCee, you need to go into law enforcement. One observation from you and there goes Tasker, confessing all.

DeleteIn a way you should be relieved that you weren't charged. Given the police's record of pinning crimes to innocent people. The detectives sound fascinating, I have never met one, leading a crime free life as I did.

ReplyDeleteYou mean you've got away all your like with everything as well.

DeleteEdit: Also there is some justice for Mrs. Leeman, the pub was turned into a care home.

ReplyDeleteI think her shop was some distance from the pub. However, there might be some care home residents who believe they are spending the rest of their lives in the Green Bottle. I might put my name down.

DeleteI thought your blog title was about Sting and his group?

ReplyDeleteHe'll be watching you.

DeleteEvery move you make. Every breath you take.

DeleteOh my word that jogged a memory of getting booked underaged in a pub in NZ. Pub age in NZ was 20 in those days. I was 16. Pubs were the only place to hear live music on a weekly basis. I was drinking (of all things) sarsaparilla. I was genuinely there for the music but the law doesn't distinguish.

ReplyDeleteWere you like Calamity Jane in the bar trying to sound tough when she asks: "Make mine a sarsaparilla"?

DeleteThe age had been 18 in Britain since the 1920s, but I found it surprising when I went to Belgium aged 15 that there were no restrictions.

Authority figures have an alarming effect on the innocent.

ReplyDeleteEspecially if they were brought up to respect them, and most of us were until more recent times.

Delete'Contrary art student attitude,' yes, that's me, I suppose, and a female to boot! I liked your friend's response. We were once pulled over by the police on the way to a tarts and tramps ball. All four of us were dressed as tramps and the police were very high handed until they came to inspect my boyfriend's driving license which stated that he lived at the police station where his father worked. Sudden change of attitude from the fuzz!

ReplyDeleteHe made a career out of it.

DeleteThe "fuzz". There's a 1960s expression.

The sarsaparilla comment reminded me of the scene in one of the 'Road' movies, where Bing and Bob (in the guise of hardened prospectors) go into a bar in the Yukon and Bing asks for a flagon of rotgut (or something like that). Bob asks for a glass of milk, only to be nudged by Bing, with a look that says "Hey, remember we're rough mountain men!") Bob gets his meaning; "In a dirty glass" he adds with a snarl and a scowl.

ReplyDeleteI like the scene in Calamity Jane, when she goes up to the bar all tough and says "Make mine a sarsparilla"

Delete