Failing ‘A’ Levels at school was not much of a setback. Such were things in the nineteen-sixties, I soon received offers to train as a Chartered Accountant. That lasted for four years, but I failed the professional exams and left to train as a science teacher. I stuck that for just four months before returning to unqualified accountancy work, an unmitigated disaster.

There was a repeating pattern, scraping through early exams without much effort, and thinking I could do the same again as things got harder. You can’t. Basically, I never did the work.

It was a long way short of where I thought I should be, and damaging to self-respect and mental health. I felt I should have done much better at school and gone on to university like many of my friends. I wanted to try again to prove I could do it, but getting in would not be easy because, unlike today, places were limited. People told me it was foolish, that the same would happen again and I would fail the exams and become unemployable. I should try again to qualify as an accountant. I was not going to listen to any of that. The best advice came from my friend Brendan, “For goodness’ sake don’t cock it up again”, mock anguish on his face as he imagined the consequences. Somehow, I knew that if I did, this time it would not be through lack of effort. It gave me a new sense of direction.

Older students sometimes got in to university without formal qualifications, but I would have been deluding myself to try. If my exam record told me anything at all, it was to learn to work and study effectively, and gain confidence. I needed to take ‘A’ levels again.

Inspired by reading interests, I switched from the sciences to the humanities, and started working towards ‘A’ Levels in English Literature and Geography. It was deadly serious, a last chance. I could not mess things up again. I took them part-time in less than a year. It was exciting and reckless.

I handed in my notice at work to free up the time needed. The idea was to swap permanent employment for short term contracts. But I found only four months’ paid work. After Christmas I stopped trying and signed on the dole (unemployment benefit) for four months. It paid my rent and kept the mini-van running. Financially, I hardly noticed a difference. It would be impossible now the rules are stricter and the benefits more miserly.

If that seems reprehensible, it was almost a lifestyle choice in those days. Some spent decades on the dole, students signed on during university vacations, and writers have told how the dole enabled them to develop their craft. Some justify it by suggesting that the cost has been recovered many times over through higher taxation, which may be true, but only for a minority.

I began to study by correspondence course, but then along came two strokes of luck. One was finding a one-year English Literature course at Park Lane College in Leeds. It was intended for re-sit students, and they tried to dissuade me, especially as I had never studies English Literature at any level, but they had space and accepted my course fee. Another student had similar aims and background, and we were a great source of inspiration to each other. That is why attending a class beats a correspondence course nearly every time. You need to be with others of similar purpose.

The other, in Geography, was that my cousin borrowed a set of notes from one of her friends who had got an A Grade. They were exquisite, and showed me what I needed to know. Is it possible to fall in love with someone through the beauty of their geography notes? With a little extra help from a friend who was a geography teacher, I decided to do that one on my own.

The English Literature class cut the course down to the essentials. It is not necessary to study every text on the syllabus when you have to choose which ones you answer questions on. I applied the same principle to Geography. One section covered weather, vegetation and soils, but as you could answer questions on only one of these in the exam, I just did soils. Similarly, where the syllabus offers choice of geographical region, I studied only those on which I planned to answer questions.

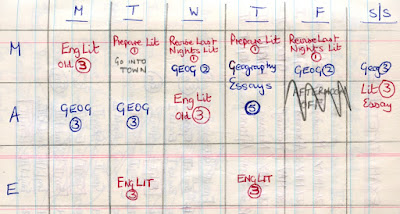

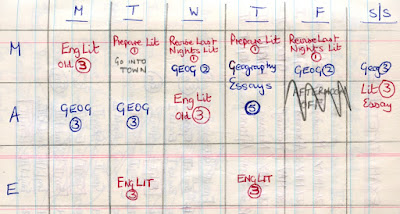

I managed to maintain focus and not mess about. I got up at a sensible hour and planned my time. I went for brisk walks after breakfast and sat down to work: three hours every morning, three hours every afternoon, plus three hours twice a week at college. I planned what I needed to cover and by when, and largely managed to stick to it.

Other ideas came from Dennis Jackson’s ‘The Exam Secret’ and Harry Maddox’s ‘How To Study’: get a copy of the syllabus to ensure you know what you are doing; narrow down your notes to things you can use in the exams; get copies of previous papers and practised answering questions under exam conditions; use memory aids such as mnemonics and mind maps; pretend to give talks on topics; attempt to emulate role models, i.e. people who are good at what you want to do. Above all, make sure you know exactly what is required of you in the exam. I never had before.

Meanwhile, I had been applying for university places. It had not gone well. Of

the six universities you were allowed to choose, three had rejected me

outright, and the others had set a high bar. I put Hull as first choice,

which wanted two grade Bs, and Lancaster second, which had asked for grades B and C.

I got two grade As.

In the nineteen-sixties and -seventies, ‘A’ (Advanced) Level grades were awarded competitively. The top 10% got grade A, the next 15% grade B, and so on down to grade E which was the lowest pass grade. Overall, 70% passed. The next 20% received an ‘O’ (Ordinary) Level equivalent and the lowest 10% a straight Fail.