Failing ‘A’ Levels at school was not much of a setback. Such were things in the nineteen-sixties, I soon received offers to train as a Chartered Accountant. That lasted for four years, but I failed the professional exams and left to train as a science teacher. I stuck that for just four months before returning to unqualified accountancy work, an unmitigated disaster.

There was a repeating pattern, scraping through early exams without much effort, and thinking I could do the same again as things got harder. You can’t. Basically, I never did the work.

It was a long way short of where I thought I should be, and damaging to self-respect and mental health. I felt I should have done much better at school and gone on to university like many of my friends. I wanted to try again to prove I could do it, but getting in would not be easy because, unlike today, places were limited. People told me it was foolish, that the same would happen again and I would fail the exams and become unemployable. I should try again to qualify as an accountant. I was not going to listen to any of that. The best advice came from my friend Brendan, “For goodness’ sake don’t cock it up again”, mock anguish on his face as he imagined the consequences. Somehow, I knew that if I did, this time it would not be through lack of effort. It gave me a new sense of direction.

Older students sometimes got in to university without formal qualifications, but I would have been deluding myself to try. If my exam record told me anything at all, it was to learn to work and study effectively, and gain confidence. I needed to take ‘A’ levels again.

Inspired by reading interests, I switched from the sciences to the humanities, and started working towards ‘A’ Levels in English Literature and Geography. It was deadly serious, a last chance. I could not mess things up again. I took them part-time in less than a year. It was exciting and reckless.

I handed in my notice at work to free up the time needed. The idea was to swap permanent employment for short term contracts. But I found only four months’ paid work. After Christmas I stopped trying and signed on the dole (unemployment benefit) for four months. It paid my rent and kept the mini-van running. Financially, I hardly noticed a difference. It would be impossible now the rules are stricter and the benefits more miserly.

If that seems reprehensible, it was almost a lifestyle choice in those days. Some spent decades on the dole, students signed on during university vacations, and writers have told how the dole enabled them to develop their craft. Some justify it by suggesting that the cost has been recovered many times over through higher taxation, which may be true, but only for a minority.

I began to study by correspondence course, but then along came two strokes of luck. One was finding a one-year English Literature course at Park Lane College in Leeds. It was intended for re-sit students, and they tried to dissuade me, especially as I had never studies English Literature at any level, but they had space and accepted my course fee. Another student had similar aims and background, and we were a great source of inspiration to each other. That is why attending a class beats a correspondence course nearly every time. You need to be with others of similar purpose.

The other, in Geography, was that my cousin borrowed a set of notes from one of her friends who had got an A Grade. They were exquisite, and showed me what I needed to know. Is it possible to fall in love with someone through the beauty of their geography notes? With a little extra help from a friend who was a geography teacher, I decided to do that one on my own.

The English Literature class cut the course down to the essentials. It is not necessary to study every text on the syllabus when you have to choose which ones you answer questions on. I applied the same principle to Geography. One section covered weather, vegetation and soils, but as you could answer questions on only one of these in the exam, I just did soils. Similarly, where the syllabus offers choice of geographical region, I studied only those on which I planned to answer questions.

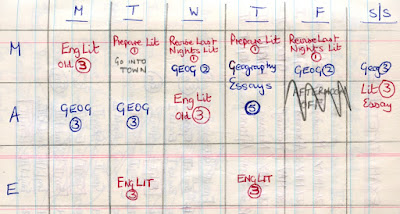

I managed to maintain focus and not mess about. I got up at a sensible hour and planned my time. I went for brisk walks after breakfast and sat down to work: three hours every morning, three hours every afternoon, plus three hours twice a week at college. I planned what I needed to cover and by when, and largely managed to stick to it.

Other ideas came from Dennis Jackson’s ‘The Exam Secret’ and Harry Maddox’s ‘How To Study’: get a copy of the syllabus to ensure you know what you are doing; narrow down your notes to things you can use in the exams; get copies of previous papers and practised answering questions under exam conditions; use memory aids such as mnemonics and mind maps; pretend to give talks on topics; attempt to emulate role models, i.e. people who are good at what you want to do. Above all, make sure you know exactly what is required of you in the exam. I never had before.

Meanwhile, I had been applying for university places. It had not gone well. Of

the six universities you were allowed to choose, three had rejected me

outright, and the others had set a high bar. I put Hull as first choice,

which wanted two grade Bs, and Lancaster second, which had asked for grades B and C.

I got two grade As.

In the nineteen-sixties and -seventies, ‘A’ (Advanced) Level grades were awarded competitively. The top 10% got grade A, the next 15% grade B, and so on down to grade E which was the lowest pass grade. Overall, 70% passed. The next 20% received an ‘O’ (Ordinary) Level equivalent and the lowest 10% a straight Fail.

Though it was long ago, I applaud your tenacity and your ambition. You made it with flying colours. Perhaps first time round you just did not have the motivation to drive you to A level success. I did okay in my A levels first time round but I could have done a lot better. When I enrolled at The University of Stirling I felt like an impostor until I saw the results of my first assignments on a noticeboard. I was right there at the top and I felt ten feet tall.

ReplyDeleteWe all could have done better the first time. It's surprising how few of my cohort went to university (around 15 out of 60) and that was from a grammar school. Basically, it was a social class effect. The older you are, the more motivated you tend to be.

DeleteYes, knowing how to apply oneself and how to study for exams are critical skills in pursuing higher education, that's for sure. Too many people assume it just happens "by magic" or without effort. Glad you figured it out!

ReplyDeleteI now believe that almost anyone could pass A Levels if they are motivated and adopt the right techniques, and those with any sense could get high grades. We were never taught this in the 1960s.

DeleteI did A and S levels in the late 50s, and dud well. But advanced education was a real zero sum game. Then one chance only at every level after age 11, including uni finals where a fail in one part of one exam over ten days after three years of coursework and study abroad, could lose your entire degree. You emerged with nothing. That did happen to a couple of friends who hadn't caught on to the studying requirements. Many years later they got to try for a degree when Open U was created. It was an unnecessarily brutal system. I think it's changed considerably now.

ReplyDeleteIt certainly has changed. The statistics are that around a third of those now at university would not have passed 11+ in 1960, and around half went then pass 11+, including all who then went to university, would now get first-class degrees.

DeleteThis entry shows how much things have changed. I did my A levels in the early 70s and then went to university on a full grant - aka my fees were paid and I got a cheque each term which was enough to live off. I worked in the holidays, and continued to pay rent. When I graduated I had money in the bank (earned by me, no parental support) - how things have changed. Now students graduate in debt.

ReplyDeleteSimilar for me, but now they admit nearly 40% into university compared with about 10% in 1970 they say it's unaffordable. They will be all hell to pay when most of the loans have to be written off.

DeleteAgree with the percentages. The UK seems to have adopted the US model of everyone should go to university.

DeleteI recall one of my old school reports, 'is intelligent and reads well but needs to better apply himself to his school work', which was quite accurate.

ReplyDeleteSo many of us were under-achievers. Schools should have spotted it.

DeleteTwo Grade As, excellent! I got high marks in most things, but never really applied myself as I knew I wouldn't be allowed to stay at school past legal leaving age. I encouraged my kids to stay, but all of them left and got paying jobs without finishing high school. The youngest did begin year 12 and made it through three terms, but then we moved and he was legally old enough to quit so he did and got a job instead.

ReplyDeleteI remember several who, despite having the qualifications, were either not by their palents to go to grammar school or, if they did, to stay on for 'A' Levels, usualy because of cost.

DeleteTwo grade As - excellent result, but don't you wonder whether your original schools failed to find ways to motivate students who clearly had the intellectual means, to obtain (before leaving school), the necessaries to prove they at least knew HOW to learn. My Dad used to say that passing exams didn't mean anything other than that you know how to learn - and could, therefore be expected to learn the skills for a trade, job, or profession.

ReplyDeleteI agree with your dad. And, yes, many have since said that the school seemed to have interest in those they thought would not get to university or college. If you wanted extra help you paid a private tutor, but most of us were unaware they existed.

DeleteWow, two grade As - terrific! I applaud to that, but even more I applaud to your strong will and discipline, Tasker. Very well done!

ReplyDeleteOn reflection, reasing how to motivate the self-discipline was as important as the actual results. But I was very pleased to get those results.

DeleteI did my 'A' levels late and I think it gave me a reason to want to learn about things. Education is not about rote learning but realising what a complicated beautiful world we live in, and the discipline of the restricted boundaries of exams allows us to open up.

ReplyDeleteSo true. Although I did a lot of rote learning, geography sketch maps for example, the opening up of ways of seeing the world were enthralling, and have stayed with me since. You get a lot more out of doing A-levels late.

DeleteHaving read your blogs for quite some time and marvelled at your memory it is no surprise to me that you gained two A levels. I think that many schools did and still do fail their pupils. My brief experience of secondary school teaching, while gaining a post-grad teaching certificate, made me feel that so much was formulaic and a waste of time. I applied only for work in art schools. I knew students were there because it was where they really wanted to be. As a result they worked hard and with great enthusiasm. And they learnt! (If they messed about I like to think they did so creatively!)

ReplyDeleteIt's definitely easier to be motivated when older. My memory is mainly rehearsal because I go over things a lot.

DeleteI like that one: "I'm not messing about, I'm being creative." Actually I remember reading that some silicon valley computer companies encourage employees to spend a certain amount of time each day playing with different bits of software because it generates the new ideas on which they depend.

I love the style of those books , very south by southwest

ReplyDeleteDon't see it, but they are certainly of their time. No hope you mean my writing?

Delete