Accountancy: it certainly taught me how the world works. I dropped out before finishing training, but was in long enough to see clients and businesses of every type and size. Most are long gone. Going to Leeds now, the place is unrecognisable.

This is the cover of a Leeds Building Society passbook showing the Society’s headquarters at the corner of Albion Street and The Headrow around 1970. The Society was then called The Leeds and Holbeck, but changed name around 1994.

On the upper floors you can just make out the offices of a solicitor, Scott, Turnbull and Kendall, also long gone. I used to sit in one of those windows carrying out their audit, looking across the Headrow to Vallances records and electrical shop, watching people walk past, wondering where they were all going and what they were thinking. It was one of the most pleasant and interesting audits we did. I remember being amused by the ‘deed poll’ name changes: Cedric Snodgrass for one. Why ever did he change his name?

Vallances’ buildings are now a leisure and retail complex with rather too many wine bars, coffee shops and restaurants, like most city centres.

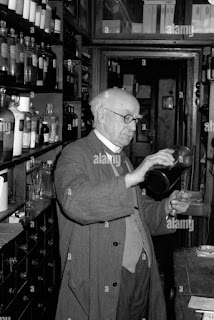

We audited a city centre pharmacist, Mr. Castelow of 159 Woodhouse Lane. Even then he was a throwback to Victorian times. His shop is now replicated (unfaithfully in my memory) as an exhibition in a Hull streetlife museum.

There were travel agents, hairdressers, bookshops, garages, a coal-merchant, charities, an insurance broker, builders, a plumbers’ merchant, a wet-fish supplier and a firm that owned several smaller cinemas and dance halls in Leeds. There was a man who bought second hand metal-working machines from defunct British factories and renovated them for export to India and China (I still know all about pillar drills and horizontal borers). We even audited a model agency. Every one has a story.

There was a firm that made broadsheet-sized photographic printing plates by coating aluminium with light-sensitive chemicals. The aluminium came in heavy rolls, possibly a metre thick and a metre high, from suppliers such as Alcan. They had to be lifted around the factory on overhead beams. I remember going in with another trainee one Saturday morning to check that the stock taking had been carried out accurately, and the other trainee spent most of the time playing with the lifting gear, moving rolls around to try to confuse me. When the audit senior arrived to see how we were getting on the other trainee took our worksheets and said that “he” had finished and all seemed in order. Bastard.

Not all our clients were in Leeds. There was a haulage company from Selby. I was delighted recently to spot one of their trucks, a family firm still trading after all these years.

There was a firm that made television adverts in an old cinema in Bradford, mainly the voice-over-stills that appeared at the end of regional ad-breaks or in local cinemas. One was for a car-wash, another for a toupee-maker. I think they almost offered me a job when I suggested they made an ad in which a man wearing a wig drives through a car-wash in an open-topped car and emerges looking spick and span. But they did make more ambitious films too, including one for lager on location in Switzerland. It was an auditors’ (and taxman’s) nightmare that the crew and actors were paid in cash out of a suitcase.

Amongst the larger businesses were the cloth warehouses and clothing manufacturers. One was not especially pleased when I discovered they had moved stock across the financial year-end in order to understate profits.

Then there were the public companies quoted on the stock exchange. One was a collection of dyers, spinners, weavers and rug-makers in factories around Leeds and Bradford. I often came away from the dyers with a free rug that had been returned because of a fault with the colours. They brightened up the shared house I lived in.

You visited these businesses, talked to the bosses and the people who worked there, checked over the books and produced sets of accounts. You knew how wealthy people were, and commercially sensitive things you had to keep quiet about no matter how wrong you thought they were, such as a new wages assistant being paid more than the senior who was training her.

Oh yes! It certainly taught you how the world works.