(First posted 6th October, 2015. 1,050 words)

Andrew and I were speaking in hushed voices, trying to look as if we were working.

“G-eight”

“Splash”

“B-nine”

“Miss”

“G-nine”

“You’ve hit Mr. Hawkwind.”

We were playing

Partners and Seniors. It was based on

Battleships, a pencil and paper game for two players.

In

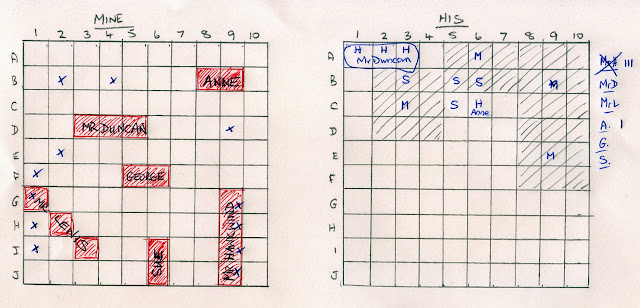

Battleships, each player draws two 10 x 10 grids for their own and their opponent’s fleets of warships, and positions their own fleet secretly in their own grid. Typically, they would have an aircraft carrier occupying five squares, a battleship occupying four, a destroyer and a submarine of three squares each, and a minesweeper occupying two. Neither player should be able to see the other’s grids.

The objective is to sink your opponent’s fleet before they sink yours. There are many variations but we played it as follows. Players take turns to shoot by naming a square in the opponent’s grid. If the square is occupied by one of the opponent’s ships then it is announced as a ‘hit’. If the square is adjacent to an opponent’s ship it is a ‘splash’. If the square is neither occupied nor adjacent it is a ‘miss’. A ship is sunk when all its squares have been hit. Players use their second 10 x 10 grid to record the results of their shots and to decide where to target subsequent shots.

Except we weren’t playing

Battleships. Our game had evolved into

Partners and Seniors. In place of warships we had Chartered

Accountants. Instead of aircraft carriers, destroyers and minesweepers,

we had partners, seniors and articled clerks from the firm where we

worked. Mr. Hawkwind was one of the partners. He occupied four squares.

We were working out of the office on the most mind-numbing of all the audits we did. You could be there for months putting ticks on ledger cards. It was like disappearing off the face of the earth.

The client was a cloth merchants, an old family firm. They bought rolls of cloth from the manufacturers in every weight, weave, colour, stripe and herringbone imaginable, and re-sold it in suit lengths – the amount needed to make men’s bespoke two-piece or three-piece suits, with or without extra pairs of trousers. The rolls of cloth were stored elsewhere in the building, away from the damaging effects of heat and light. The cool, shadowy stillness of the warehouse had a strange musty smell: a mixture of dyes, preservatives and the scent of the cloth itself.

The firm supplied just about every tailor and outfitter in the country. In other words, they had a lot of customers: twenty trolleys full. For each customer there were one or more yellow sales ledger cards around eight by ten inches in size. The cards were arranged alphabetically in boxes on long-legged, wheeled trolleys like miniature babies’ prams. They referred to them as buses. “Have you seen the ‘B’ bus?” “Could I have the ‘QR’ bus when you’ve finished?”

Some of the office staff had been there for decades, from the days when most clerical jobs were done by men. They all still wore suits and ties, and kept their jackets on all day. Only the office manager, in the room next to ours, worked in his shirtsleeves. He was not an attractive sight: a fearsome, grossly overweight man who always left his unpleasant outdoor shoes, or in winter his stinking wellington boots, beside the radiator.

One of the clerks, in his mid-forties, all worry-lines, teeth and thick glasses, would have been tall had he stood upright, but was bent over from years at a desk. As he stooped to push the ledger buses, his jacket draped itself around the cards as if trying to consume them.

One Friday afternoon we listened, able to overhear the office manager tell the clerk, completely out of the blue, that he was no longer needed. “You realise this is absolutely no reflection on you in any way whatsoever,” he tried to reassure him, as if it made things better. The clerk seemed unable to reply. A week or two later his job was taken by a new girl straight from school.

The business was beginning to struggle and trying to cut costs. Demand for made-to-measure suits was falling because of changing fashions and cheaper, ready-made, ‘off-the-peg’ garments. One floor of the warehouse was now empty. Within not so many years the family owners would decide to give up the ghost and lease the building to the old adversary: the Inland Revenue.

But that was in the future and the firm still had a few years left to run. As auditors, we were required to check that every sale the firm had made during the year had been correctly recorded on the correct ledger card. So for several weeks each year, a couple of articled clerks would spend their days ticking off the cards against the order books and sales invoices. Then, to ensure they received an appropriate breadth of professional experience, they would go through all the incoming payments and tick those off against the ledger cards too. One year you would use a red pen, the following year a green, and then back to red again. The exhilaration was tangible. You really looked forward to getting up in a morning.

What made the task seem even more superfluous was that the ledger cards were partly computerised. They were printed by machine, and each yellow card carried three dark-brown, machine-readable, magnetic stripes to record all the transactions. It was an early, primitive system, but really, wouldn’t some kind of statistical sampling been sufficient to ensure the cards were reasonably accurate? Any mistakes that crept in could have been corrected as and when they were discovered. The firm must have wanted everything checked by the auditors. Articled clerks were paid a pittance so it didn’t cost a lot. Perhaps they needed to keep tabs on the inexperienced staff they were now taking on.

I never did find an error. That is not to say there weren’t any, but the job was so soporific that any I came across would probably have got ticked correct anyway.

Is there any wonder we invented diversions such as

Partners and Seniors and firing rubber bands at paper cups to brighten up the day?

“J-nine”

“You’ve just sunk Mr. Hawkwind.”

Mr. Hawkwind would have sunk us if we’d been caught.