My father was always puzzled by a strange teenage memory. In 1937 he went with his parents to visit distant relatives at Boston in Lincolnshire. In one house, an elderly Jew was sitting at a high desk in skull cap and prayer shawl reading a Hebrew bible, his finger tracing the curious lettering right to left across the page. Who could this have been? My father was never aware of any Jewish relatives. He began to wonder whether he had imagined the whole thing. The truth, when it emerged, is like a tale from Dickens.

Years later, after his parents were gone and there was no one left to ask, the image kept returning to bother him like a recurring dream. He wished he had paid more attention, except you don’t when you are sixteen, or even when you are thirty-three or forty, his ages when his mother and father died. He struggled to reconstruct the event: the one-day railway excursion from Goole; meeting his mother’s cousin, Lucy Mann, who gave them dinner (i.e. lunch); climbing the three hundred and sixty five steps to the top of Boston Stump with his father (i.e. Boston St. Botolph, the tallest church tower in England). But the man with the Hebrew bible remained a mystery.

|

| The Hull Daily Mail, 1937 |

Much of the story made sense. Railway excursions were very popular in the nineteen-thirties before the days of mass car ownership. They ran to destinations far and wide from every major town and city. The London and North Eastern Railway advertised numerous trips from Hull and Goole in 1937, including several to Boston. One such excursion, for a fare of four shillings and nine pence (24p in new money), left Goole at 10.50 a.m. on Sunday 7th November and would have arrived in Boston before one in the afternoon. Presumably they spent the afternoon there and returned that evening.

On the way home, my grandfather, amused by what they had seen, began to tease my grandmother about her distant relative. It was still unusual for people from a small Yorkshire town to encounter other religions or ethnicities, even for those who had seen service abroad during the First World War. It was cause enough for suspicion to be Roman Catholic, or sometimes Methodist. “Well, you kept quiet about that all these years, didn’t you!” he mocked. “I didn’t realise I’d married a Hebrew!”

My grandmother’s cousin, Lucy Mann, is also no mystery. The two cousins had spent the First World War together in service as shop assistants at Southport in Lancashire. They had a common bond: the childhood loss of a parent. Lucy’s father had died of heart disease in 1893 when she was two, and my grandmother’s mother of kidney disease in 1910 when she was fourteen. Lucy can be found in my grandparents’ wedding photographs in 1919. They remained in touch for the rest of their lives.

But who was the man with the Hebrew bible? My father gradually came round to thinking he could have been married to one of his mother’s aunts. We looked for clues in the snippets of family history I traced, but to no avail. None of the twelve aunts we found fitted the bill.

The truth came to light only after my father had died. It was the result of a set of events that would never occur today – like a nineteenth century Dickensian tale, convoluted as a Catherine Cookson saga.

It begins in the eighteen-fifties. My grandmother’s maternal family lived in a hamlet called Amber Hill in the Boston fens: an expanse of low lying farmland to the west of The Wash in South Lincolnshire. It is a bleak, wet landscape of isolated villages surrounded by field after field of crops. But for a network of deep drains and pumping stations originally powered by windmills, it would quickly turn back into marshland. You could imagine it as Holland; in fact one fen is actually named Holland Fen. Families were large, and the children went on to have large families themselves. Work on the land was hard and death came early and often.

My grandmother’s mother was one of at least twelve siblings. The two eldest, both girls, married the same man, the elder sister having died at the age of twenty. Between them they had fourteen children with the surname Sellars. One, Thomas Sellars, moved north to the town of Goole, then a booming port in Yorkshire. It promised a kinder life than on the land, with plentiful work on the docks, on the railway, and in the industries springing up around the town. Thomas found work as a coal porter, married and quickly had four children, but one died soon after birth, and then his wife died. It was May, 1906. Thomas was left alone with three children: Albert aged four, Beatrice, three, and Edmund, one.

Other siblings and cousins had moved to Goole too, including my grandmother’s parents. It would not have been entirely alien to them because, like the Boston fens, the land is flat and artificially drained. The families remained close, some lodging with or living next door to each other. They would have rallied round straight away to help Thomas with the children. A working man at that time could not have looked after them alone.

Soon, however, Thomas was on his own again. He remained in Goole, but the 1911 census shows him living alone in lodgings. Albert is back with Thomas’s parents in the Lincolnshire Fens. Edmund, the youngest child, had died in 1908. Beatrice is nowhere to be found. It seemed that she had disappeared from the records.

It is not unusual to have loose ends in family history research. Sometimes they are never resolved. My grandmother had at least fifty first cousins just on her mother’s side of the family, some of whom also seem untraceable.

Thomas died three years later in 1914. He is buried with his wife and children in a pair of forgotten and neglected plots in Goole cemetery. My grandmother would certainly have remembered her cousin Thomas and his family, being only a little older than his children.

This sad tale was all we could find for many years. We knew most of it before my father died. At that time it seemed to have absolutely no connection to the man with the Hebrew bible. It never occurred to either of us there might be one.

But the great thing about internet genealogy is that not only does it provide untold resources for tracing your family history, it also facilitates communication between distant relatives and others researching the same families. One day, out of the blue, I received a message from Beatrice’s grandson, actually my third cousin once removed, and the rest of the story fell into place. The man with the Hebrew bible acquired a name.

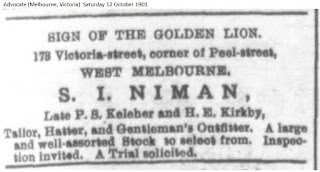

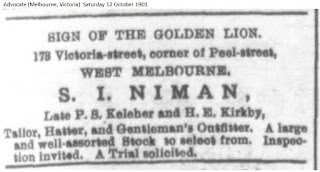

He was Samuel Isaac Niman, born in 1867 at Plock in central Poland.

When he was two his family moved to England and settled in Leeds where

he grew up. He trained as a tailor and at some point during the

eighteen-nineties emigrated to Melbourne, Australia, to set up in

business as a gentleman’s outfitter.

|

| The Melbourne Advocate, 1901 |

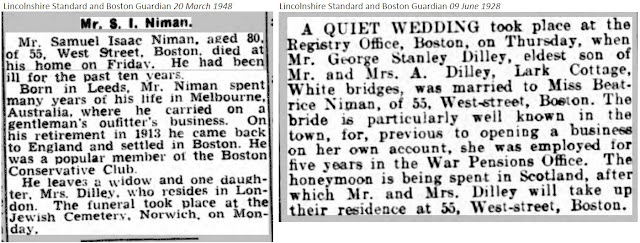

One of Thomas Sellers’ sisters, Mary Ann Sellars, had also moved to Melbourne. When, how and why remains unknown. She had been in domestic service in the 1891 census, but had then become another of those loose ends that disappeared from the family tree. It transpired that she had married Samuel Isaac Niman in Melbourne in 1900.

News of the death of Thomas’s wife would have been slow to reach them in 1906. One imagines letters sent back and forth by sea with an interval of six or seven weeks between dispatch and delivery. They would have touched upon the uncertain future of Thomas’s children. Exactly how the dialogue then developed one can only guess, but it seems the Nimans were unable to have children of their own and it was agreed they should take one of Thomas’s to live with them in Australia. In March, 1907, Mary Ann sailed from Melbourne, arriving in London in mid-May. Then on the 26th September she sailed back from Liverpool accompanied by five-year old Beatrice, and Beatrice Sellars became known as Beatrice Niman. One wonders what the little girl thought, sailing off to a new life on the other side of the world with an aunt she had known for just four months.

|

| The Lincolnshire Standard and Boston Guardian, 1933 |

The Nimans remained in Melbourne for a further six years until, in

July 1913, they returned to England and settled in Boston. Samuel started another business

there, apparently with Mary Ann and Beatrice, eventually opening a ladies clothing

shop at 55 West Street. They lived on the premises, which is where my

father and his parents would have visited them in 1937. Beatrice by then

was married with children of her own, but she still lived in Boston and

may also have been present. We no longer know how well Mary

Ann knew my grandmother or whether Beatrice remembered her. She would

have remembered very little about her time in Goole with her own

parents, but might have visited on returning from Melbourne in 1913

because her father, Thomas Sellars, was still alive. One can only

wonder. The more you find about family history, the more questions you

have.

So my father had not imagined the whole thing. The man with the Hebrew bible was real. He was Samuel Isaac Niman, the husband of one of my father’s mother’s cousins. Beatrice’s son remembered him as very religious. As a child he would sit on his knee at the high desk as he read the Hebrew bible.

Sadly, my father died six or seven years before I was able to tell him.

After Samuel's death, Mary Ann went to live with Beatrice and her family who had moved to Muswell Hill, London. She died there aged 84 in 1956.