links to: introduction and index - previous day - next day

Thursday 1st September 1977

Our walking holiday in Iceland continues.

|

| Leaving Strutslaug - the hut is in the mid distance on the left |

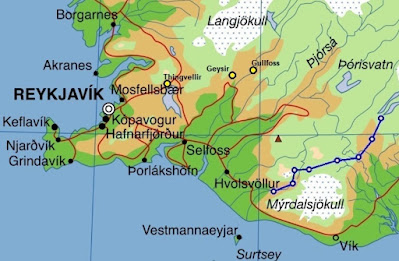

On the road again, or rather, up a frozen river in a snowstorm and a slide down a glacier. Today, we skirt the southern edge of the Torfajökull ice cap and move to Hvanngil.

|

| Paul and the ‘bridge school G.T. boys’ in the distance, leaving us behind yet again |

Neville boasts of being an expert ice slider on account of his skiing experience. Bridge School Mike is entirely the opposite. At least that’s one thing he can’t do. As I follow Neville by sliding down on one foot keeping perfect control by punching the ground with mittened fists, Mike shoots past head first on his back at about fifty miles an hour. Still, he seems to be enjoying it.

We shelter from the weather in a snow cave to eat our sandwiches.

Later, we have to cross a stream. Steve and I are too close to each

other with one rock common to both our routes. He gets there first. I

fall full length but escape with only a wet leg. By then the snow, which had turned to rain, has

stopped and the wind soon dries my trousers, but only after

Paul takes full advantage of the opportunity to make sardonic comments.

Today I am carrying the billy cans. They jingle-jangle constantly behind me against my metal mug. Now I know how cats must feel with bells on their collars. Everyone carries their share of the equipment and everyone does their share of the housekeeping – washing up, making sandwiches, burying rubbish and fetching water. Paul does all the cooking on a primus stove. Perhaps the main selfishness, which I have only just caught on to, is in arriving at huts as early as possible and bagging the best sleeping spots.

The countryside gradually turns greener as we get nearer the enormous Markarfljót river. My day off yesterday at Strútslaug has paid off. In the afternoon I zoom along with Paul and arrive at Hvanngil first, but as it is the most comfortable hut so far, there is no real advantage.

Ed is once more a long way behind. He really should have rested yesterday, too. He struggles along, but his feet are now worse than mine were. He has bad blisters and swollen ankles, and must be in awful pain. Somehow, he keeps going and will not let anyone else carry his share of the equipment.

Someone jokes that his injuries have been imposed by the killjoy Icelandic government. They run a country in which only low alcohol beer is permitted. Despite being the size of Ireland, there are only eight shops allowed to sell spirits. Paul says they do permit the sale of home-brew beer kits, but insert a leaflet warning it is against the law to put any sugar in. Blisters and swollen ankles are decreed by statute.

|

| The Hvanngil hut |

Hvanngil (pronounced “Kwanngil”, possibly meaning water ravine) is massive. It has two floors. Upstairs, accessed by ladder, is equipped with tables, chairs and mattresses. It is also very warm: in fact too warm for super-acclimatised Paul who decides to sleep downstairs in the horse food trough. This leads to speculation about what his house in Newcastle-under-Lyme is like: stable downstairs, corrugated iron roof, Karrimats instead of beds, food cooked on paraffin stoves and eaten with spoons out of mess tins, a shovel outside the back door for digging convenience holes in the neighbours’ gardens, leaky and draughty windows, no heating, mugs and toilet rolls hanging by strings from hooks in the walls.

|

| Notebook Pages |

The real reason Paul went downstairs to sleep in the horse trough only occurs to us later. From her broad accent, I spot straight away that Judi is from Leeds.

Dick Phillips is every bit as formidable as his photographs suggest, frighteningly serious and knowledgeable, confidently in command of all around through thick dark beard and equally thick dark spectacles. In the morning, I catch the flash of his piercing gaze observing me critically as I dawdle languidly over a late breakfast. I quickly finish and start tidying and washing up. Bang goes any chance I had of being invited back as a walk leader.

(next part)

Some names and personal details have been changed. I would be delighted to hear from anyone who was there.