New Month Old Post: first posted 19th April, 2019.

My generation was not as open with our parents as our children are with us, at least not in my part of the North of England, or maybe it was just me. I never told my parents I went in pubs. Not even when old enough. The police told them. It was Easter Sunday, 11th April, 1971.

It was the day after I had been with three friends to The Green Bottle in the curiously named Spawd Bone Lane, Knottingley. The pub was packed with noisy, holiday-weekend drinkers, and we took little notice of a short-haired man in a suit sitting alone at a table in the middle of the room until he asked us one by one to go over to have a few words with him. He was a detective investigating a vicious attack on an elderly lady the previous afternoon*, although we did not know that until later.

I can still remember some of what he asked – name, age, address, where I been between 4.30 and 6.30 the previous afternoon, and where I worked. I told him I was an accountants’ clerk with Goodwill and Ledger in Leeds, to which he said, “Oh! Do you know Mr. Black?” I said no, there was no Mr. Black where I worked, to which he replied that he worked at the Huddersfield office. It so happened that we did have an office in Huddersfield, and being naïve and trusting, thinking it a genuine question, I said I wasn’t sure but thought I might have seen that name on the letterheads, and that Mr. Black might be a partner at the Huddersfield office. It seemed to arouse the detective’s interest. I had never been grilled by the police before, and found it unsettling, although I tried hard not to show it.

The detective moved on to my friends, one of whom was in the middle of a Fine Art degree, with a contrary “art student” attitude, full of the deep and mysterious philosophies to which such beings are prone. He was going through a phase of answering questions with enigmatic answers, that’s if he could be bothered to answer at all. When approached on a train in the Midlands by a woman carrying out a travel survey, he told her he was on his way to Johannesburg. No matter who was asking, or how serious the situation, he took the same line. It was also the case, coincidentally, that he had the same surname as me, which drew the obvious follow-up from the detective.

“Oh! Are you related?”

“I suppose we must be.”

“What does that mean?”

“Are we not all related in some way?”

The detective was suspicious. Did he think I had given him a false name, that of my art student friend? We had a bit of a laugh about it afterwards.

When you consider the gravity of the situation, it was not really funny at all, but we were still at that stage of youthful innocence which takes little seriously. Without really being part of it, we liked to imagine we followed the trendy, counterculture of underground bands and magazines such as Oz which was about to face an obscenity trial. You don’t realise now when you see old clips of bands such as Black Sabbath, just how excitingly anti-establishment they seemed, even in name. The police were joked about: you would see “Screw the Pigs” scrawled in four-foot letters on garage doors. This pushing of the limits, I would now say, was only possible because England, on the whole, was a much safer and law-abiding place than it is today, which makes the attack on the old lady all the more shocking. And of course, we did not yet know the awful details of the incident.

The following day, being Easter Sunday, I was at home, going through the pointless motions of revising for my accountancy exams. Dad called me down to the front room where two more short-haired men in suits wanted to see me.

“These two gentlemen are police officers, and would like to ask you some questions.”

Being the sort of person who feels guilty even if not (you know, when the teacher asks who made that silly noise and you go red, terrified she thinks it was you, even though it was someone else), it really scared me. I had to explain about the pub in Knottingley and about being questioned, and the two detectives went off satisfied, but it felt very awkward.

And that’s how my parents found out I went in pubs, although, they probably knew already.

There is now no sign The Green Bottle ever existed. It closed for good and was boarded up by 2009, burnt out in 2010, demolished, and is now the site of a care home.

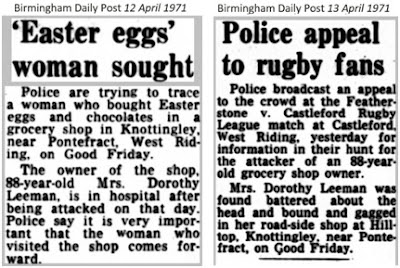

*From newspaper archives, I can see that the elderly lady

was 88 year-old Mrs. Dorothy Leeman. She had been beaten around the head,

bound, gagged and robbed of £80 on Good Friday in her roadside shop at

Hilltop, Knottingley, Yorkshire. She never properly recovered and died

less than six months later. It was an appalling attack and I don’t believe anyone was ever caught.