My vision issues make reading and participating in comment quite challenging just now, but I continue to enjoy your blog posts which the computer reads for me.

Today, I want illustrate life's vicissitudes through the story of my mother's lifelong friend Doreen. They are the kind of things we like to pretend do not happen.

Shortly after my parents married, they rented the two-bedroomed terraced house where I spent my first years. It needed thorough cleaning, so Mum busied herself scrubbing floors, washing windows, scouring the kitchin, sweeping the yard and hanging curtains. I can imagine the hot, damp smell of soap flakes, coal tar soap, scouring powder and disinfectant. There were few detergents. She had escaped her claustrophobic village and mother for her own little house in town, where she built a new life and blossomed.

In the back-bedroom of the house across the lane at the rear, a woman of similar age lay in bed-rest at her mother-in-laws', heavily pregnant with twins. She watched my mother at work and wondered who was this energetic and pleasant-looking young woman she had never seen before. Her mother-in-law came across to make contact, and Mum went across to meet Doreen. They had lots in commom and talked for hours.

They became lifelong friends. We visited each others' houses all the time. I called her Aunty Doreen. I have a lovely photograph of my pregnant (with me) Mum with Doreen, her husband and the twins walking along the promenade on a sunny day-trip to the seaside. They are all laughing and happy.

A few hears later we moved to a bigger house in the next street, so saw a little less of each other, but still visited often. It did not therefore surprise me on returning from school one afternoon to find the twins at our house. They were a girl and a boy then aged around ten. I was around seven. What I did not know was that they were there because their father had been taken seriously ill at the mill where he worked. He had had a massive heart attack. After a time someone knocked on the door and my mother sat the twins down at the table because she had something to tell them. "Your daddy's died" she simply said. It must have been almost impossible to say. They both burst into floods of tears. I didn't really understand but knew it was awful. People at the mill remembered how disturbing it was to see his overalls and shoes still at his peg. His body lay at rest at hone in the front room until the funeral. Doreen was still in her thirties.

But life goes on. With support from relatives, friends and neighbours Doreen brought up the twins into teenagers. A few doors along the street lived Maurice, a railway engine driver who had lived alone since his parents had died a few years earlier. He was a good-looking, gentle giant of a man, shy and quiet. The twins thought him wonderful and he became like an uncle who played with them. He formed a close friendship with Doreen and eventually proposed. Doreen was forty-two, Maurice about thirty-four.

"But he's so much younger than me," Doreen told by mother.

"Gerrim married," Mum replied.

So she did, with my mother looking radiant and lovely as Matron-of-Honour. She had never been a bridesmaid before.

The photographs show a happy day, although as I have seen in other families including ly owm, her late husband's mother does not look entirely behind the idea. The marriage worked and lasted over thirty years.

On his days off, Maurice liked to do odd-jobs, and I sometimes found him round at our house quietly washing the windows.

Then at around the age of sixty, Doreen became very ill with bowel cancer.

"They'll be taking me out of here in a box," she told my mother visiting her in hospital. And we all thought that was true.

And yet, against all the odds, she survived. She had an ileostomy operation and it was successful. It was my mother who died two years later of breast cancer and Doreen survived her by twenty years before falling into old-age and dementia. Maurice lived on for another ten years.

To get through life without encountering such dreadful ups and downs is very fortunate. For the rest of us that do, I don't know how do manage to cope. We must be very resiliant. It's not all rosy, is it!

Google Analytics

Wednesday 22 February 2023

Doreen

Wednesday 15 February 2023

Guitar Books

These are the books that taught me to play guitar. They came new with my first guitar in 1965.

Actually, books can't teach you to play a musical instrument. You have to motivate and do it yourself, and if you've got it you'll get there, and if not you won't. It is hard-earned. I remember so many whose desire exceeted their application.

'Tune A Day' was helpful by starting me off with two-chord songs such as 'Some Folks Like To Fret And Scold', played just on three strings, but I had to keep trying over and over again before it sounded anything like it should. Most find that being able to change between chords is the most difficult bit. It can also be hard to know when the guitar is out of tune.

You then struggle to master more chords using more strings, and pehaps after a few months you begin to realise you can do it. But as a guitar teacher in Hull (Tim Keech) told me, "it takes you ten years before you realise how crap you are" (which is true of so many other things too).

Once I could play a bit, there was another book that did in fact teach be quite a lot, Hal White's 'Leeds Guitar Method' from the nineteen-fifties. It explained things clearly, such as on this page about Augmented Chords, and followed up with contempory songs that used them; in this case Dickie Valentine's 'The Finger Of Suspicion Points At You'. My copy of the book came from a long-forgotten school friend whose name and address I am disturbed to see written in the front. I wonder what became of him.

Play regularly for ten years and you become reasonably competent. When I lived in a shared house we often bought a big bottle of cider each and played through the Beatles' Songbook.

Here are a couble of multi-track recordings I made in the severties: a J.S.Bach two-part invention, or if that's not your thing, you might recognise the other piece as an improvisation around the Beatlers' song 'You're Gonna Lose That Girl'. You don't have to tell me now how messy it is, but I was making much of the improvisation up as I went along. I wish I could still do it as well as that now.

If you can't see the videos they are at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q1li2a1TfDo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kK71bqVVIFk

Sunday 15 January 2023

Night Cleaner

My mother would have said it was the only proper job I ever had. Being stuck in an accountants’ office didn’t count. Nor did poncing around in universities. But twelve-hour nights in a canning factory, well, that was the kind of work her family had always done, and people from her village too.

I was a night cleaner: not the sort of cleaner that normally comes to mind with mops, buckets and toilets, but sturdier stuff involving wellington boots, waterproofs and hosepipes. Our job was to clean the factory machinery overnight in readiness for the following day’s production. I spent three university summers there. It was very well paid.

Some of the permanent employees resented the students for the easy opportunities they had, especially Ken the electrician. His job seemed mainly to keep everything covered in a thick layer of grease to protect switches and circuits from all the water swilling around, but it was no match for our high pressure hoses. From the ladders we climbed to wash stray peas and other vegetables from the hoppers and seamers, it was impossible not to short-circuit his electrics now and again. It sent him apoplectic.

“Call yourselves bloody students? You don’t even have the intelligence you were born with. What the hell do they teach you at university? You can’t even piss straight.”

I once accidentally filled his toolbox trolley with water, the stream from my hose tracing a perfect arc across the factory ceiling. What he thought of that is unrepeatable. It involved the contents of my underpants and what would happen to them were I to do it again.

The “regulars” knew how to keep the students in their place. The names they gave us, the sayings they used, the jokes they told, were outrageous. Mick, another night shift “regular”, had one of the most creative and imaginative senses of vulgarity I have encountered. He said if anyone tried to drink his tea while he was in the “bog” (toilet), he would tear open their throat and get it back while it flowed through. He didn’t just spit in his cup to make sure no one drank from it, he rubbed a certain part of his anatomy round the rim.

When Nevil Shute (in ‘Slide Rule’) wrote that people from this part of the world were “brutish and uncouth, … the lowest types … ever seen in England, and incredibly foul mouthed”, he simply didn’t get it. It might have been unsophisticated, but it was clever and hilarious.

Donny, however, was different. He was gentle and softly-spoken. He was the night cleaning foreman, our boss. He did not put you down when you missed something, but patiently showed you what was wrong so that you gradually learnt the job. Being quiet, he came in for a lot of teasing from the other “regulars”.

Much of this took place in the factory canteen. Typically, we would start our shift at six in the evening and help in the factory until production ended. We would then take a meal break before the canteen closed. One of the canteen staff was called Josie, a divorced lady who lived in Donny’s village. With her lovely dark hair, she must have been extremely attractive when young. It was made out that Donny had a soft spot for her. This led to rampant invention about what Donny dreamed about. How often did he walk secretly past her house? When would he pluck up the courage to ask her out? Did he keep her picture on the wall next to his bed? Josie laughed, but was clearly embarrassed. Donny said nothing, but took it in his stride.

The final year I worked at the canning factory was its last. It was to close permanently at the end of the season. The “regulars” were served with redundancy notices. During the final week only Donny and I were on nights. We often finished early except for in the yard where we had to wait for daylight. Donny asked if I would run him to his girlfriends’ in my Minivan, finish on my own outside when it was light, and clock off his time card at six, which I did. It was the first I had heard of a girlfriend. He revealed it was Josie.

I didn’t see Donny again, but thirty years later I noticed an obituary notice in the local newspaper which my father always saved for me. It was Josie. The final line read, “With heartfelt condolences to Donny, her long-time loving partner”.

Sunday 6 November 2022

The Songwriter

Another item from the old electric guitar case: the November 1977 edition of The Songwriter, the magazine of the International Songwriters Association. Not very inspiring, is it! I have no idea how I acquired it or why I kept it. Perhaps I thought I would be the next Bjorn or Benny.

Can you become a songwriter by reading a magazine? It seems to me like all that stuff about how to be a published writer. If you look up “memoir blogs”, for instance, there are lots of people all too ready to tell you how to do it, but not many who actually do.

Did J. K. Rowling spend her time reading magazines about how to write books, or did she just get on with it?

The chap on the cover of ‘The Songwriter’, by the way, turns out to be one Reg Guest, apparently a successful arranger and session musician, but not much of a songwriter. The president and founder of the Association, Jim Liddane, does not seem to have written many songs either.

I think it’s another item for the recycling bin.

Tuesday 1 November 2022

Weekend in College

(New month old post: first posted 23rd September, 2015)

You been tellin’ me you're a genius since you were seventeen,It was as if Steely Dan’s phenomenal ‘Reelin’ in the Years’ was aimed directly at me, cutting through the pretentiousness to the stupidity beneath. It was actually four months but might just as well have been a weekend for all the good it seemed to do. With the anticipation of arrival smothered in a blanket of disillusion, I detested myself as much as the subject of Becker and Fagen’s song.

In all the time I've known you, I still don't know what you mean,

The weekend in the college didn't turn out like you planned,

The things that pass for knowledge, I can't understand.

|

| City of Leeds and Carnegie College |

It was the first of two attempts to escape accountancy. After four mind-numbing years, I decided it was not the career for me, and applied to train as a science teacher. You needed five G.C.E. Ordinary level passes, and to have studied your specialist subjects to Advanced level. In other words, you did not actually need to have passed the Advanced level. That was me exactly. I didn’t tell them about the failed accountancy exams.

It beggars belief that you could become a Secondary years science teacher with nothing better than weak Ordinary level passes in your specialist subjects. They should have told me to go away and re-sit Advanced Levels and reapply, assuming I still wanted to. Anything less would be to inflict my limited knowledge and ineffectual learning techniques upon other poor innocents. But you can talk yourself into anything if it’s on offer.

|

| Around 1960 |

The City of Leeds and Carnegie College, now part of Leeds Beckett University, was one of the loveliest campuses in Britain. It was built in 1911 in a hundred acres of parkland that once belonged to Kirkstall Abbey. Hares ran free in the woods and each spring brought an inspiring succession of leaf and flower. The magnificent main building dominated a sweeping rectangular lawn called The Acre, lined by solid halls of residence named after ancient Yorkshire worthies: Fairfax, Cavendish, Caedmon, Leighton, Priestley, Macauley and Bronte.

But instead of moving into halls, I remained off-campus in my seedy shared house. It meant not taking full part in the friendly community of cosy study bedrooms around the grassy Acre, and the activities I might have enjoyed. I felt old and awkward. The music drifting from open doorways flaunted the easy friendships within. While the Carpenters sang that they were on top of the world, Steely Dan mocked that “college didn't turn out like you planned”.

The course quickly became tedious. Chemistry classes were interminable, like being back at school. I began to sink into the old malaise and find fault in everything. A biology technician “humanely” despatched rats for dissection by cracking their necks on the edge of a bench. We sampled the vegetation growing on The Acre lawn, my accountant’s brain adding up the data almost before the other students had got out their calculators. In English classes, reading through a play, I realised that some of the others were not fluent readers. It was astonishing. They were training to be teachers for goodness’ sake.

We were sent out on teaching practice. I found myself in a Comprehensive School on a council estate. After two weeks, we were asked to plan and teach a small number of lessons ourselves. I had good ones and bad ones. In the best, observed by the teaching practice tutor, the children used Bunson burners, all happy and engaged in what they were doing. Do they still let them do such dangerous things? Fortunately, no one saw the worst from which I was saved only by the school bell.

The school had none of the liveliness of the grammar school I had attended myself, and staff made no secret of their dissatisfaction. “Here I am with a First in English,” said one, “and I’m supposed to teach kids who have no interest in reading anything at all.” And one of the most inspiring teachers left to open a pottery.

Despite good marks, the doubts grew as I returned to my old employer to earn money over Christmas. The uninspiring course, the mediocrity, the dismal school I’d seen, it was not what I wanted. It was not a substitute for university. More hopes and dreams dashed by another abandoned course. What now?

I was by no means the last to leave. A few went on to successful teaching careers, but many never taught at all. During the year that my course would have finished, the press was rife with accounts of unemployment among new teachers. Despite a chronic shortage just two years earlier, Governments had not planned for the falling birth rate. Around two thirds of newly qualified teachers were unable to find jobs.

One poor girl in London had previously been guaranteed a post, but after staying on at college an extra year to improve her qualifications with a Bachelor of Education degree, she now had to find work outside teaching. Perhaps it was fortunate I did leave.

It was thirty years before I visited Beckett Park again. The passage of time gave rise to quite an unsettling experience. I was haunted by half-remembered faces and snatches of conversation from a particularly intense episode in the past: here is where I usually managed to find a parking space for my Mini; across there is where I resented a tutor telling me I would have greater authority if I stood straighter and walked with shorter steps; that window, in Leighton Hall, is the study bedroom where a girl I seriously fancied took me one afternoon for nothing more than a cup of coffee and a long talk.

Ghosts aside, the place looked much the same. Most of the original Edwardian campus survives, although the internal use has changed, such as residences replaced by staff offices and teaching rooms, with students bused-in from off-campus and financed very differently.

Smoke gets in your eyes. You can convince yourself anything is right when you’re desperate enough.

[The original post was even longer and more over-written than this, but if you are interested, it is still here]

Thursday 27 October 2022

Strings

New guitar strings fitted today on the Epiphone dreadnought. The last ones had been on since 2018 and were getting a bit dull and smelly (grease from your hands). It’s a long job taking about an hour and a half, and I always dislike doing it, but it’s worth it in the end.

I don’t usually throw the old ones away in case I break one and need a spare – something that has only ever happened once or twice in my life. I looked in my old electric guitar case: there could be every string I’ve had in fifty years. Have put the metal ones for recycling.

There are other things in the guitar case too, but I’ll save them for later.

Saturday 15 October 2022

More Thoughts On Clients

I was encouraged by the interesting comments on my last post about the businesses I came across while working in accountancy in the nineteen-seventies, and the further thoughts they sparked off. The following captured my ambiguous feelings about it at the time:

Brown paper parcels containing vouchers,

Cash books and day books, bank statements in pouches,

Ledgers and ledgers, both sales and bought,

Ticking up postings requires little thought.

One big difference between then and now was the lack of computerisation. Nearly all records were handwritten. Some were in beautiful leather-bound ledgers, and there was a sense of pride and skill in being able to keep them neat and tidy in fountain pen, without mistakes and corrections.

Others might be in scruffy self-duplicating docket books. It was interesting to follow them around factories, matching them to drums of dye colour, or to trace them from lengths of cloth to the despatch of finished items of clothing. This was done to ensure the accounting systems were working correctly and detect possible fraud (which was rarely found).

But often the books of smaller clients would be brought into our own offices where you might be stuck for several weeks bored to tears, hence my parody of ‘Favourite Things’.

I made distractions for myself. When we took on a model agency as a new client I was asked to produce a set of example book keeping entries for the owner to follow so that she knew how to fill them in. To the annoyance of my boss I used the names of famous models such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton, causing him to exclaim: “For goodness’ sake, Tasker, we’re a firm of Chartered Accountants, not Monty Python’s Flying Circus!” Too late. They were already inked into the first page of the cash book.

We also prepared sets of annual accounts for clients, filed them with the Inspector of Taxes on their behalf and dealt with their tax affairs. As a result I have never been afraid of dealing with outfits like HMRC or the DSS.

You could also get stuck of larger clients checking off lists against each other. It wasn’t called “double entry” book-keeping for nothing. At one cloth warehouse it took several weeks to work through the sales ledgers. Statistical sampling and tests of significance would not have been considered adequate then. We checked nearly everything.

Another big difference was the sheer variety of types of business. We made so many more of our own things before globalisation. Now, Central Leeds seems to be predominantly financial rather than physical, and nearly everything takes place at desks in offices.

Computers sucked the life blood out of everything.

Wednesday 12 October 2022

Clients

Accountancy: it certainly taught me how the world works. I dropped out before finishing training, but was in long enough to see clients and businesses of every type and size. Most are long gone. Going to Leeds now, the place is unrecognisable.

This is the cover of a Leeds Building Society passbook showing the Society’s headquarters at the corner of Albion Street and The Headrow around 1970. The Society was then called The Leeds and Holbeck, but changed name around 1994.

On the upper floors you can just make out the offices of a solicitor, Scott, Turnbull and Kendall, also long gone. I used to sit in one of those windows carrying out their audit, looking across the Headrow to Vallances records and electrical shop, watching people walk past, wondering where they were all going and what they were thinking. It was one of the most pleasant and interesting audits we did. I remember being amused by the ‘deed poll’ name changes: Cedric Snodgrass for one. Why ever did he change his name?

Vallances’ buildings are now a leisure and retail complex with rather too many wine bars, coffee shops and restaurants, like most city centres.

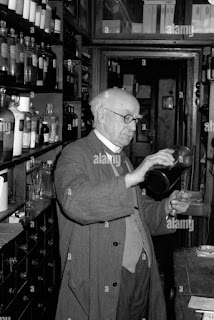

We audited a city centre pharmacist, Mr. Castelow of 159 Woodhouse Lane. Even then he was a throwback to Victorian times. His shop is now replicated (unfaithfully in my memory) as an exhibition in a Hull streetlife museum.

There were travel agents, hairdressers, bookshops, garages, a coal-merchant, charities, an insurance broker, builders, a plumbers’ merchant, a wet-fish supplier and a firm that owned several smaller cinemas and dance halls in Leeds. There was a man who bought second hand metal-working machines from defunct British factories and renovated them for export to India and China (I still know all about pillar drills and horizontal borers). We even audited a model agency. Every one has a story.

There was a firm that made broadsheet-sized photographic printing plates by coating aluminium with light-sensitive chemicals. The aluminium came in heavy rolls, possibly a metre thick and a metre high, from suppliers such as Alcan. They had to be lifted around the factory on overhead beams. I remember going in with another trainee one Saturday morning to check that the stock taking had been carried out accurately, and the other trainee spent most of the time playing with the lifting gear, moving rolls around to try to confuse me. When the audit senior arrived to see how we were getting on the other trainee took our worksheets and said that “he” had finished and all seemed in order. Bastard.

Not all our clients were in Leeds. There was a haulage company from Selby. I was delighted recently to spot one of their trucks, a family firm still trading after all these years.

There was a firm that made television adverts in an old cinema in Bradford, mainly the voice-over-stills that appeared at the end of regional ad-breaks or in local cinemas. One was for a car-wash, another for a toupee-maker. I think they almost offered me a job when I suggested they made an ad in which a man wearing a wig drives through a car-wash in an open-topped car and emerges looking spick and span. But they did make more ambitious films too, including one for lager on location in Switzerland. It was an auditors’ (and taxman’s) nightmare that the crew and actors were paid in cash out of a suitcase.

Amongst the larger businesses were the cloth warehouses and clothing manufacturers. One was not especially pleased when I discovered they had moved stock across the financial year-end in order to understate profits.

Then there were the public companies quoted on the stock exchange. One was a collection of dyers, spinners, weavers and rug-makers in factories around Leeds and Bradford. I often came away from the dyers with a free rug that had been returned because of a fault with the colours. They brightened up the shared house I lived in.

You visited these businesses, talked to the bosses and the people who worked there, checked over the books and produced sets of accounts. You knew how wealthy people were, and commercially sensitive things you had to keep quiet about no matter how wrong you thought they were, such as a new wages assistant being paid more than the senior who was training her.

Oh yes! It certainly taught you how the world works.

Thursday 1 September 2022

Lytton Strachey

New month old post (originally posted 20th June, 2016)

As a young, unreconstructed, heterosexual male from a northern working-class monoculture, it was a most unlikely book to be reading: Michael Holroyd’s biography of Lytton Strachey (1880-1932), an effete, gangling homosexual with a big nose, unkempt beard and light, reedy voice. I got it by forgetting to cancel the default selection from the book club I was in.

I cautiously dipped into its 1144 pages, wondering what on earth it was, and was quickly drawn in by the preface, an account of Holroyd’s researching and writing of the book.

Lytton’s archive was so extensive it took Holroyd five years to work through it, a period he describes as “… a way of life and an education.” As he ploughed through the plethora correspondence with its detailed accounts of faulty digestion, illness, apathy and self-loathing, he began to experience the same ailments himself, wondering whether they could be posthumously contagious. He resolved that his next subject must be someone of extraordinary vitality.

Even so, Holroyd’s life as a writer and researcher seemed hugely preferable to mine as a trainee accountant. There had to be more edifying things than an accountancy correspondence course. Constructing control accounts and trial balances was anything but an education.

If Holroyd’s account of writing the biography drew me in, his descriptions of the Strachey family had me hooked. There were numerous uncles, cousins and other visitors, many either distinguished, completely potty, or both. Holroyd describes them as “the flower of originality gone to seed.” One uncle who had lived in India continued to organise his life by Calcutta time, breakfasting and sleeping at odd times of day.

Other oddballs walk on and off stage throughout the book. One of my favourites could have been invented by the comedian Ronnie Barker. He was “dr. cecil reddie” Lytton’s one-time headmaster and a leading member of “the league for the abolition of capital-letters.” In retirement he corresponded with “lytton” from his address at “welwyn-garden-city, hertfordshire.”

Having chuckled my way through the early chapters, I became immersed in Lytton’s school and university days, identifying with his shyness and awkwardness in company, the feeling of somehow not fitting in, and his difficulty in making friends. But when he got to Cambridge University he began to thrive. He was elected to the Conversazione Society, otherwise known as the Apostles, a highly secretive group which met in members’ rooms on Saturday evenings to eat sardines on toast and discuss intellectual topics.*

Through the Apostles, Lytton became friends with leading writers and intellectuals of the day, such as Bertrand Russell, G. E. Moore, Rupert Brooke, John Maynard Keynes and leading members of the now-famous Bloomsbury Group of writers, artists and intellectuals which included writers Virginia Woolf and E. M. Forster, and the post-impressionist painters Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.

Many rated Lytton as one of the cleverest people they had encountered, but immediate success eluded him. His history degree was Second Class, his application to the Civil Service unsuccessful, and he was twice rejected for a University Fellowship. He found himself back home writing reviews for periodicals and generally drifting. Churning out articles left little of his scant energy for the great work he hoped to write. Eventually, at the age of thirty-one, he did produce a book, a history of French literature, but it brought neither the wealth nor the success he sought.

I still envied him. I would have been happy to get into any university, let alone Cambridge, and it would have been the sauce on the sardines to be invited to join a secret club. My not-so-exclusive group of mates who met in the Royal Park Hotel to drink five pints and tell sexist and racist jokes did not have quite the same intellectual mystique.

Lytton’s life at this time seemed no more purposeful than mine, with a similar pattern of futility and wasted energies. But it must have been nice, when feeling a bit fed up as Lytton often did, to be able to take oneself off to relatives in the Cairngorms, or to friends in Sussex or Paris. He was no slave to the thirty-seven hour week and three weeks’ annual holiday.

One of the most startling revelations in Holroyd’s book was its frank treatment of bi- and homosexuality. There was irony in Lytton’s alleged response to the First World War military tribunal that assessed his claim to be a conscientious objector. When asked: “What would you do if you saw a German soldier attempting to rape your sister?” he is said to have answered: “I should try to come between them.”

Nevertheless, some women were attracted to Lytton, and Lytton to some women. At one point he proposed to Virginia Stephen (later Woolf), who accepted him, although both rapidly decided it not to be a good idea.

Then, in 1915, he was captivated by an androgynous young painter, (Dora) Carrington (known by her surname only). Their story begins when she crept stealthily upon Lytton’s sleeping form intending to cut off his beard in revenge for an attempted kiss. Lytton suddenly opened his eyes and gazed at her. Holroyd takes up the tale: “... it was a moment of curious intimacy, and she, who hypnotized so many others, was suddenly hypnotized herself.” From that moment they became virtually inseparable. They set up home together and were often simultaneously besotted with the same person, usually male.

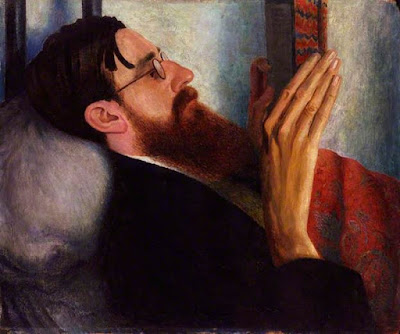

Look how much she loved him:

|

| Lytton Strachey by Dora Carrington (1916) |

In 1918, Lytton’s fortunes changed. His book, ‘Eminent Victorians’, caught the mood of a war-shocked nation, cynical and distrustful of the rigid Victorian morality that had led to the conflict. The title is of course ironic. It dismantles the reputations of four legendary Victorians. To summarise Holroyd: Cardinal Manning’s nineteenth-century evangelicism is exposed as the vanity of fortunate ambition; Florence Nightingale is removed from her pedestal as the legendary ‘Lady of the Lamp’ and revealed as an uncaring neurotic; Dr. Thomas Arnold is no longer an influential teacher but an adherent to a debased public school system; and General Gordon, the ‘hero’ of Khartoum, is shown to have been driven by the kind of misplaced messianic religiosity all too familiar to those returning from the trenches.

The book reflected the attitudes of Lytton’s Bloomsbury circle, in many ways foreshadowing how we live now, especially the displacement of public duty and conformity by private hedonism and individuality. It also revolutionised the art of biography, showing off Lytton’s virtuosity as a writer: his repertoire of irony, overstatement, bathos and indiscretion, his fascination with the personal and private.

Holroyd’s reputation, too, was shaped by his Strachey biography, establishing him as part of England’s literary elite.

For me, both Strachey and Holroyd were a revelation. Despite being worlds away from my own time, place and social class, they helped strip away the veils of convention and conformity that school, church, state and society had thrown over us. The parade of larger-than-life eccentrics showed it was not unacceptable to be different; that you did not have to follow convention or do what others expected; that not everyone had launched themselves into an upward trajectory by their twenties; that we can all have doubts and be demoralised, yet still come good.

Northern working-class England in the fifties and sixties was as rigidly Victorian as the mores rejected by Bloomsbury. People worked long hours, had few holidays and were poor. Authority went unquestioned and unchallenged. But the times they were a-changin’. There were opportunities in abundance. For me, it was not so much Bob Dylan or John Lennon that brought this message home, but a rare biography of Lytton Strachey.

Footnotes:

This was the 1973 edition of the Holroyds biography published by Book

Club Associates. The biography was revised in 1995 to incorporate material that had become

available since the earlier editions, but I still prefer the detail of

the 1973 version. There is now an enormous amount of other material

about Lytton Strachey, Dora Carrington and the Bloomsbury Group.

* The Cambridge Apostles are rumoured still to be active. Members consider themselves the elite of the elite. Membership is by invitation only and potential recruits are unaware they are being considered. Despite the secrecy, one has to wonder whether they might easily be identified by their supermarket trolleys overstocked with excessive quantities of tinned fish and toasting bread on Saturdays. They need to address this security weakness urgently.

Thursday 25 August 2022

Cameras

Last month’s post about photographic lenses and extension tubes set me thinking about the cameras I’ve used over the years. Some were also in the loft.

1950s

The Ensign took most of our family photographs until 1962 when I received a Kodak Brownie Starmite camera for Christmas and became the family photographer. This used smaller 127-sized frames (40mm square), also 12 per roll. Pictures from both the Ensign and the Starmite have appeared many times on this blog, especially indoor flash.

1974

After starting work I wanted a 35mm single-lens reflex colour slide camera. One of the most economical to buy was the Russian Zenith E. It cost £33 from York Camera Centre in January, 1973.

Comparing the quality of the Zenith images with the Ensign and Starmite negatives, you can see why it was cheap. I would have been better with something slightly more expensive, perhaps Pentax or Praktica, but the Zenith was fairly robust and I used it into the nineteen-nineties. It survived hours in rucksacks including two weeks backpacking in Iceland, and once rolled several hundred feet down a mountainside in Switzerland. Unfortunately, the fabric shutter is now torn beyond repair. As the lenses have gone to the charity shop, the camera body might as well go for metal recycling.

One nice touch was that the Zenith came with a free book, “Discover Rewarding Photography: the Manual of Russian Equipment”, which, despite its name, contained helpful hints and useful information.

1994

2001

The software for transferring images from the memory cards was awkward. You couldn’t just stick it into a computer slot like now because the ‘Camedia’ cards were enormous – seen here beside a standard SD card for comparison. I bought additional 16MB cards to take more photographs. A hundred was luxury after 35mm film. The camera was also a little heavy because it used four AA batteries. It still works but is worth at most £20 on ebay. Should it go to the electrical equipment recycling skip?

With two young children the Olympus was used a lot, but after a few years I noticed that the images had a small number of blank pixels. It seemed time to upgrade.

2006

Technology was advancing rapidly and getting cheaper too. My 7.1 megapixels Canon Digital Ixus 70 cost £169.99 in April 2006, and I still use it today. It has a similar spec. to the Olympus: a 3x optical zoom (35-105mm), a macro function and built in flash, but also an extensive range of image settings and unlimited movie time with sound. Mine is set to 3072 x 2304 pixels at 180 dots per inch which creates jpg images of 3.5MB. Even a ‘small’ 4GB SD card stores loads.

You can get much higher spec. cameras now, even on phones, but this is fine for most purposes. However, one might say that it isn’t as much fun, and doesn’t have the same mystique as the Zenith.

Not wanting to disappoint the technical amongst us, here are links to the Ensign Ful-Vue, Zenith E and Pentax Espio instruction booklets and manual.

Sunday 14 August 2022

Drought

I usually photograph places where I’ve lived. Here is one corner of my room in Leeds in the summer of 1976. The washbasin was handy for peeing in as the toilet was on the floor below. Well, you can be like a slob when you live on your own.

What do I see? Towels strewn around. Swan electric kettle, toaster and fan heater on the floor. An anglepoise lamp I still have. The wooden book rack I made at school which I still use, containing books I still have. A naff set of biros designed to look like quill pens. A tiny nineteen-fifties transistor radio in front of the mirror on the edge of the dressing table … and in the corner on the floor some bottles of water.

Yes, we had a drought in 1976. It was one of the warmest years of the last century, not surpassed until this century. The highest temperature recorded was 35.9°C (96.6°F), not quite reaching 36.7°C (98.1°F) of 1911. The drought was caused by low rainfall the previous summer which lasted through the autumn and winter. By the autumn of 1976 water was rationed in some places by means of standpipes in the streets. My parents’ house had an infestation of seven-spotted ladybirds.

Could we be heading there again? I am no climate change denier, but despite the clear upward trend I hope that once we are through it we will have experienced an outlier, at least for long enough to see me out. As for my children, both still in their twenties, they could be well-advised to move to somewhere like Fort William, Portree, Stornoway or Kirkwall, preferably on high ground not too near from the sea.

Sunday 24 July 2022

Oil Lamp

In Bright In The Background, I recalled how my brother gouged a deep groove into the front of our parents’ brand new sideboard the day after it was delivered (I wasn’t entirely blameless). I guess my brother would have been around ten at the time which may excuse things a little. But it did not put an end to our unruly “riving about” as Mum called it. We did a similar around six years later when we should have known better, when my brother was taking his ‘O’ levels and I had started work.

I can be fairly precise about the date because it was shortly after the February 1972 power cuts. Most of our electricity was then generated from coal, but the miners had gone on strike forcing the government to schedule power cuts to private homes. The Central Electricity Generating Board divided days into three-hourly time-slots and assigned homes to areas. Power was then rationed by areas. Typically, your power would be switched off for two time-slots on three days each week, and you would also be on standby at other times in case further cuts became necessary. Rotas were published in regional newspapers.

I remember being in our shared house in Leeds, playing chess by candlelight. At least we had a gas cooker and a gas fire.

Evered No. 4 Duplex

Evered & Co. Ltd.

London and Birmingham

which dates them as Victorian, perhaps from as early as 1850. All parts, including the glass shades, were original. I never thought to ask about them, or how long they had been in the family.

Mum filled the lamp she had brought home with fuel, trimmed and adjusted the wick, and set it alight. As far as lighting was concerned, there might well have been no power cuts at all. It was easily bright enough to read by quite comfortably.

That was the last time it burned. A week or so later, the two naughty too-old-to-be-boys knocked it over and broke the shade. Zoom in and you can see where my brother stuck it back together with Evo-Stik.

And so, fifty years later, it found itself in our loft. And a leaflet came through the door from a Mr. Madgewick of Wombell. It gave me great expectations. The leaflet was covered in drawings of gold and jewellery, coins, military items, furniture, musical instruments, china and ceramic, typewriters, cameras … I immediately thought of the oil lamp in the loft.

Instant cash paid

And he did. It was like the daytime TV antiques programme ‘Dickinson’s Real Deal’. At first he said he was not interested, that he might have been had the shade been intact. But as he started to leave without it, he suddenly turned back and “to do me a favour” named a figure and pulled a roll of bank notes out of his pocket. I’m not kidding it could have been £10,000 thick. It was my turn to pretend not to be interested. Eventually, he and counted some notes into my hand.

Of course, I’m sure I’ve been done.

Monday 11 July 2022

Lenses and Tubes

I’ve been in the loft again. This time it was old photographic stuff.

The lens on my present digital camera (a 7.1 megamixels Canon Digital Ixus 70 bought in 2007 for £170) has a 3x optical zoom and a 12x digital zoom if one is happy with loss of image quality. That, of course, is nowhere near as good as more recent digital cameras where 20 megapixels and a 25x optical zoom (or more) would not be uncommon, and even many camera phones would now better it. Even so, I still find it adequate for everyday purposes (note to family: it may be time I had a new one).

But in the old days of film cameras, lenses were usually of fixed focal length. You could get zoom but they tended to be expensive, so people usually used interchangeable fixed lenses, typically a standard lens, a wide-angle lens and a telephoto lens.

My Zenith E came with a standard 58mm lens which was a little long, a bit like always being on 1.2x zoom. It also had quite a narrow field of view, so I bought a 35mm wide-angle lens for indoor shots, and also a 135mm lens for distance. My understanding is that the 135mm lens is equivalent to 2.7x zoom. For 4x zoom I would have needed a 200mm lens, and for 8x zoom a 400mm lens. As well as being expensive, they would have been very heavy to carry around when out walking.

Here, captured from mid-auditorium by the 135mm lens, is my brother receiving his degree at the University of Bradford from “that old man with a dirty hanky” as my aunt put it (he was younger than I am now). I stood up to take the picture, the Zenith gave off its customary loud “clunk”, and I managed to sit down again before people on the rows in front turned round to see what the noise was.

But what did we do for close-ups? My digital camera has quite a useful close-up ‘macro’ feature, but lenses were not so straightforward. They could be near-focused to some extent, but true close-ups required a set of extension tubes (sometimes called extension rings) which screwed between the lens and camera body.

I had a set of three tubes of 7mm, 14mm and 28mm, which, in combination, gave seven different levels of magnification. They screwed together with such satisfying precision. I took this close-up of Southern Iceland from a map of Scandinavia in an atlas in 1977.

Here are the lenses and tubes down from the loft. They are destined for the charity shop, although whether they are worth anything when these days you can pick up top of the range Leica, Canon and Nikon stuff for next to nothing, I don’t know.

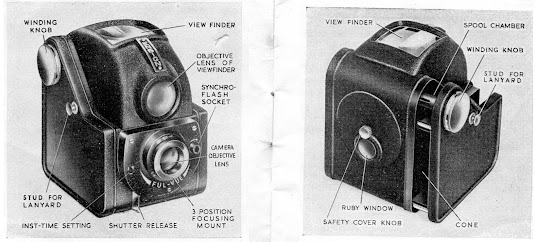

And for the true nerds, here is the instruction leaflet for the extension tubes.

Thursday 23 June 2022

A Body Like Mine

I was always a thin and awkward child, and not very strong. It might have been genetic, but I also put it down to having had whooping cough at six months, a serious illness at that age. Whichever, it left what would now be called self-esteem and body-image issues, although, of course, such things did not exist in those days.

You could count each rib individually, and my sternum ended in what looked like a hole in the centre of my chest. My collar bones were lumpy protrusions jutting from the tops of my shoulders like razor shells, as if I’d been pegged out on washing line. School swimming lessons, scrutinised by the masses of girls watching from the balcony each week (how did so many manage to get out of it?), were humiliating. I grew to 6 feet (183cm) tall but weighed only nine and a half stones (60.3kg or 133 pounds), a body mass index (BMI) of 17.5, very much underweight in other words.

Who would want a body like mine? Not me. I wore jumpers all year round, kept my jacket on, and avoided beaches and swimming pools. I couldn’t gain weight whatever I ate. That might sound enviable, but not when you’re too thin.

I revived the sadistic games teacher’s gym exercises, puffing and panting through press-ups, sit-ups, heel-lifts and squat-jumps. Press-ups were particularly difficult, but starting with just one or two several times a day in secret, I gradually built up to five, then ten, then more. But I looked just as thin.

I sought salvation in the small ads discreetly scattered throughout the press, and sent off for details of the Charles Atlas body building course. The ads omitted to mention the price, which was £8, too much, even after starting work. They sent reminders, and after a while reduced the price to £6. They sent more reminders and the price fell to £4, so I went for it. Someone told me if I’d waited longer it would have dropped to £2.

Charles Atlas, Angelo Siciliano (1893-1972), claimed to have transformed himself from a scrawny, seven-stone weakling into ‘The World’s Most Perfectly Developed Man’ after having sand kicked in his face by a bully. Thus began one of the longest and most memorable advertising campaigns of all time.

In one unforgettable ad, a frail young man is taunted in front of his girl friend with “Hey, Skinny! Yer ribs are showing!”. When he protests he is pushed in the face and told “Shut up you bag of bones!” It could have been me, except that I didn’t even have a girl friend.

The course consisted of exercises to help gain strength by setting muscles in opposition against each other, trademarked the ‘Dynamic Tension’ method. One exercise was to form a fist with one hand, and press downward against the other hand in front of you for several seconds. This was then repeated with the other hand on top. Another exercise involved pulling hooked hands against each other.

It is not difficult to see how regular repetition might build muscle. However, to gain weight the course included diet sheets touting overpriced food supplements. It was also padded out with tips on jujitsu, wrestling, boxing and feats of strength to amaze your friends, such as tearing a telephone directory in half and lifting a pony into the air. A triumph of advertising over substance. Perhaps I did gain a bit of muscle, but nothing like Charles Atlas. I wouldn’t have wanted to be like him anyway. I decided against a trip to the beach to check whether my physique was now more of an attraction than a curiosity.

In the end, I just got used to it. My BMI gradually crept up to the lower end of normal and more or less stayed there. I still do a few exercises each morning, not Atlas ones but bending and stretching, and lifting a pair of 2 x 5 Kg dumb bells, not to get fitter or stronger, but not to get worse. They nearly killed me carrying them from Argos.

Take note of Gillian Lynne, the ballerina, who was still carrying out a daily exercise routine (more demanding than mine) and teaching and demonstrating dance moves at 90. She said that just one day off because you feel a bit tired is one step down the slippery slope to oblivion.

Thursday 16 June 2022

Slide Copier

If you want to copy of an old photographic colour slide or negative, say, to post online or to make a copy of someone else’s slide, what do you do? You take a photo scanner if you have one (I have a Canon flatbed scanner with a film and slide copier in the lid), scan in the image (I use 3200 or 4800 dots per inch), and, of you are a perfectionist, tidy up to dust marks and scratches with Photoshop or similar. It makes for a better quality image than you ever used to get projecting the slide on to a glass bead screen.

But what did you do in the pre-computer nineteen-sixties and seventies? Think: Tandy TRS-80 introduced 1977, Sinclair ZX80 and ZX81 in 1980 and 1980, the 8-colour BBC Microcomputer in late with 1981 and the Sinclair SX Spectrum in 1982. None of these would have been capable of running photo-scanning devices even if they had been available. For example, to Hewlett-Packard Scanjet was introduced in 1987. It operated in black and white at 300 dots per inch, could handle only reflected documents and not film or slides, and cost a fortune.

So what did you do? Another trip to the loft has found my slide copier.

It was terrible. I could never get it to produce a decent image no matter what kind of lighting I used.

For example, here, in a copy from a friend’s slide, I am nearing the top of Ben Nevis in April, 1974, straight up from the Glen Nevis car park. It has not been Photoshopped. I did not even manage to get the light consistent on this one. You didn’t get to see it until the film was processed, and the cost meant you couldn’t have as many goes keep trying until it was right.

Looks like another item for metal recycling. Thank goodness for modern photo scanners.

For the sake of completeness, here are the instructions that were in the box (or download as pdf)

Wednesday 4 May 2022

Old Wires

You do odd jobs, you accumulate all sorts of bits and pieces, and you them keep because they might come in useful one day. You buy things and they wear out but you keep the bits and pieces that go with them because they might also come in useful one day. And, fifty years later, you have boxes full of all those bits and pieces, some of which may have come in useful but most of which didn’t.

Here is part of my lifetime’s collection of wires and plugs. Funny what memories they bring back!

I found the plug, socket and cable used to make an extension lead for the fluorescent light I fitted under the eaves of my loft room in the shared house in 1972, a short length of ring-main cabling from when I installed several spur wall-sockets after moving into our current house thirty years ago, and some left-over heat resistant cabling used to wire up an electric immersion heater around the same time. Then there were the transformers from old computers, printers and scanners, and their plugs, sockets and adapters. I can still identify them: RS-232, Centronics, VGA, S-Video, Ethernet, HDMI, DIN. There was even an old cordless telephone system.

And where on earth were the following electronic components from? It might have been one of the kid’s Design Technology projects at school, involving transistors, capacitors, thermistors, a photo-resistor and light-emitting diodes. They remind me of my brother’s nineteen-sixties electronic engineer’s kit, or my nineteen-seventies home-built Heathkit stereo.

How many of the following does one really need?

- spare 3, 5 and 13 amp fuses

- spare mains plugs and multi-socket adapters

- travel adapters for various kinds of power supply

- transformers for long-gone printers, scanners and computers

- cables for printers, monitors and keyboards

- USB cables

- ADSL micro-filters for connecting broadband to telephone lines

- SCART leads for video recorders

- mono/stereo audio/video jack plugs, DIN plugs, HDMI leads, S-video leads

- television aerial cables

- lawn mower cables

- electric kettle cables

- time-switches

- wall sockets, light fittings and light switches

- wiring of various lengths and thicknesses

If I don’t sort them now, someone else will have to do it. This is some of what will be going to the electrical skip at the recycling centre.

And the rest? Sorted into smaller boxes, labelled and back in the loft in case they come in useful one day.