For every multi-megabucks idea, there must be thousands that come to nothing at all. I thought I’d got one once, but it didn’t happen. Within a few months, I was down at the Labour Exchange signing on for unemployment benefit.

It was educational software. The government had decided every school should have a computer. Generous funding was provided, advice centres were set up, projects started and teachers trained. Most schools bought “The BBC Microcomputer”, a machine commissioned to accompany a television series and computer literacy project. The manufacturer, Acorn, did very well, eventually selling over half a million machines into schools and homes. A subsidiary company, Acornsoft, was also raking it in by supplying games and educational software to go with the BBC machine.

|

| Acornsoft Word Sequencing written by Ann and Russel Wills |

To be fair, educationalists had yet to understand what kinds of computer-based activities were best. Word Sequencing would have been referred to as “drill and practice” because it repetitively “drilled” learners through a sequence of practice questions. It follows the ideas of behavioural psychologists such as B. F. Skinner and their theories of conditioning. Developmental and educational psychologists, however, were sceptical of this approach, and argued that computer-based learning could be more effective by promoting playful exploration or collaboration with others.

More by luck than judgment, I found myself well-placed to work in this area having recently completed a degree in psychology and an M.Sc. in computing. My M.Sc. project had been with programs that handled language, similar to early chatbots. I got a job with a university team researching how computers might help children whose understanding of language had been held back by conditions such as deafness or learning difficulties. These children needed a lot of one-to-one support, and it was thought that computers might be able to help with the workload of psychologists, speech therapists and teachers. The team had collected thousands of carefully structured sentences from established remedial schemes, and I was taken on to write the computer programs that used these materials.

We were not using BBC computers which would not have been up to the task (they had a thousandth the speed and a quarter of a millionth the memory of a modern laptop), but in my own time I started to think about what might be done with a BBC. One idea came from an early artificial intelligence program called SHRDLU from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which was capable of holding written conversations about objects of various shape, size and colour. You could ask it questions and instruct it to move things around.

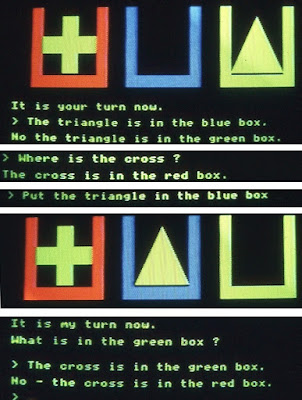

I came up with around twenty much-simplified versions of the idea, each of which just squeezed into a BBC and made use of its (rather limited) colour graphics. Some posed problems that had to be solved by asking questions and giving instructions.

|

| A sequence from one of the programs |

My supervisor started talking about the programs at academic conferences, which caught the attention of Acornsoft. The managing director came to see us: a tall, young-faced man, precisely how you might imagine a successful computing entrepreneur to be, who uncurled himself languidly from the driving seat of his sporty Jaguar, took one look at the software and said: “I’ll buy it”.

They would pay 25% royalties and, going by Word Sequencing, would expect to ship at least twenty-five thousand during the first year. F-ing hell! Do the maths. Twenty-five per cent of twenty-five thousand at £9.95 a time. How long before I too would be languidly uncurling myself from the driving seat of a sporty Jaguar?

Then the university management heard about it. I was hauled before one of the deputy vice chancellors and firmly told that anything I invented was the intellectual property of the university: it had been developed on university equipment and despite doing it in my own time my contract specified I had no own time.

Acornsoft already had the programs anyway, and we had also proposed a new project under which they would fund my university salary to dream up educational software to create collaborative learning activities over computer networks. We had only vague notions of what these activities might be, but four brand new BBC Microcomputers with as yet unreleased Econet nodes rapidly arrived free from Acornsoft – over two thousand pounds-worth of kit.

Then we waited for the programs to be published. And we waited for the new project agreement to arrive. And we waited longer. And my fixed-term employment expired but Acorn assured us the new agreement would soon be with us, so I worked for almost a month unpaid. And then Acorn ran into financial difficulties due to problems with the new Acorn Electron and Acorn Business Computer and heavy research and development costs, and was broken up and sold off. My programs were never published and the new project never started, and I had to sign on the dole. That was my brave new world of 1984.

For a short time, I really believed I’d made it. It would never have turned me into a Bill Gates or Steve Jobs, but when the average U.K. house price was still under £30,000, it could have set me up very comfortably.