Who needs brains any more except to ponder how computers and calculators have changed the way we do everyday calculations?

At one time we needed brains for long multiplication and long division, drummed into us at primary school from time immemorial. It is so long since I tried I’m not sure I can remember. Let’s try on the back of a proverbial envelope.

|

| Long multiplication and long division with numbers and with pre-decimal currency |

To do it you had to be able to add up, ‘take away’ and know your times tables – eight eights are sixty four, and so on – but just about everyone born before 1980 could do these things without having to think.

Those of us still older, born before say 1960, could multiply and divide pre-decimal currency – remember, twelve pence to the shilling, twenty shillings to the pound. You had to have grown up with this arcane system to understand it. Perhaps we should have kept it. It might have put foreigners off from wanting to come here and there would have been no need for Brexit. As the example reveals, even I struggle with the division.

|

| Logarithms and Antilogarithms |

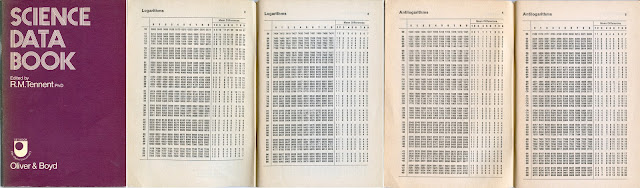

Then, there were logarithms and antilogarithms, as thrown at us in secondary school. To multiply or divide two numbers, you looked up their logs in a little book, added them to multiply, or subtracted to divide, and then converted the result back into the answer by looking it up in a table of antilogs. For example, using my dinky little Science Data Book, bought for 12p in 1973:

To multiply 2468 x 3579:

log 2468 = 3.3923; log 3579 = 3.5538; sum = 6.9461; antilog = 8,833,000

To divide 3579 by 24:

log 3579 = 3.5538; log 24 = 1.3802; subtraction = 2.1736; antilog 149.1

It’s absolute magic, although the real magicians were individuals like Napier and Briggs who invented it. How ever did they come up with the idea? It was not perfect. Log tables gave only approximate rounded answers and it was tricky handling numbers with different magnitudes of ten (represented by the 3., 6., 1. and 2. to the left of the decimal points), but it was very satisfying. You needed ‘A’ Level Maths to understand how they actually worked, but not to be able to use them. Some also learned to use a slide rule for these kinds of calculations – a mechanical version of logarithms – but as I never had to, I’ll skip that one.

|

| A Slide Rule |

Due to a hopeless lack of imagination, I left school to work for a firm of accountants in Leeds. Contrary to what you might think, our arithmetical skills were rarely stretched beyond adding up long columns of numbers. We whizzed through the totals in cash books and ledgers, and joked about adding up the telephone directory for practice. The silence of the office would be punctuated by cries of torment and elation: “oh pillocks!” as one desolate soul failed to match the totals they had produced moments earlier, or a tuneless outbreak of the 1812 Overture as another triumphantly agreed a ‘trial balance’ after four or five attempts.

| |

| A 1960s Sumlock Comptometer. |

But when it came to checking pages and pages of additions we had comptometer operators. Thousands of glamorous girls left school to train as Sumlock ‘comps’, learning how to twist and contort their fingers into impossible shapes and thump, thump, thump through thousands of additions in next to no time without ever looking at their machines. By using as many fingers as it took, they could enter all the digits of a number in a single press. It probably damaged their hands for life. I still don’t understand how they did it. There was both mystery and glamour in going out on audit with a comp.

|

| A 1950s Friden Electromechanical Calculator |

Back at the office we had an old Friden electro-mechanical calculating machine. What a beast that was. I never once saw it used for work, but we discovered that if you switched it on and pressed a particular key it would start counting rapidly upwards on its twenty-digit register.

“What if we left it on over the bank holiday weekend?” someone wondered one Friday. “What would it get to by Tuesday?”

Fortunately we didn’t try. It would probably have burst into flames and set fire to all the papers in the filing room. But we worked it out (sadly not with the Friden). It operated at eight cycles per second. So after one minute it would have counted to 480, after one hour to 28,800, and after one day to 691,200. So if we had started it at five o’clock on Friday, it would have got to 2,534,400 by nine o’clock on Tuesday morning. So, counting at eight per second gets you to just two and half million after three and a half days! It shows how big two and a half million actually is.

The obvious questions to us awstruck nerdy accountant types were then “what would it get to in a year?”– about two hundred and fifty million, and “how long would it take to fill all twenty numbers in the top register with nines?”– about thirty nine million million years. As the building was demolished in the nineteen eighties it would have been switched off long before then. But what would it have got to?

|

| An ANITA 1011 LS1 Desktop Calculator (c1971) |

The first fully electronic machine I saw was a late nineteen-sixties ANITA (“A New Inspiration To Accounting”), one of the first of many truly cringeworthy acronyms of the digital revolution) which looked basically like a comptometer with light tube numbers. Then, fairly quickly with advances in integrated circuits and chip technology, came the ANITA desk top calculator followed by pocket handhelds that could read HELLHOLE, GOB and BOOBIES upside down, and 7175 the right way up. Intelligence was as redundant as comptometer operators. We revelled so much in our mindless machine skills that I once saw a garage mechanic work out the then 10% VAT on my bill with a calculator, and get it wrong and undercharge me. It can still be quicker to do things mentally rather than use a calculator.

Around 1972, my dad saw one of the first pocket calculators for sale in Boots. It could add, subtract, multiply and divide, pretty much state of the art for the time, but at £32 (about £350 in today’s money) and not as compact as now, it required large pockets in more ways than one. I told him it was ridiculously overpriced. Infuriatingly, he ignored me and bought one. On the following Monday they reduced the price down to just £6. It was his turn to be annoyed but the store manager refused to give a refund. He stuck with that calculator for the next thirty years.

How often now do we even use calculators? Not a lot for basic arithmetic. Do we ever doubt the calculations on our computer generated energy bills and bank statements? Do we check the VAT on our online purchases? Do accountants ever question the sums on their Excel spreadsheets? Just think, a fraction of a penny here, another there, carefuly concealed, embezzlement by a million roundings, it could all add up to a nice little earner.

Great story! I worry that the people who've grown up in the age of electronic calculators and computers are missing out. We've seen many instances of shop clerks who can't make change when for some reason their electronic cash register fails them.

ReplyDeleteThanks for dropping by Jean. I'm beginning to realise that (more by chance than design) several of my blog posts are about skills we are losing.

DeleteFascinating post,Tasker. A girl in my class told me proudly that she was going to be a comptometer operator - I was suitably impressed.

ReplyDeleteI think basic skills in the three Rs were more profoundly drilled into us. Now, there's so much to be 'got through' that if a child misses it first time round, that's it!

I remember the word compometer but I never found out what they were. I wondered if the operator would be comptompting at the machine.

DeleteI think education is missing something these days.

DeleteAndrew - Ha!

All I know is that I love the calculator app on my phone. Nice big numbers so I can see it easily! I for one do not miss doing calculations by hand.

ReplyDeleteThere is satisfaction in doing it manually.

DeleteUrgh... logarithms. At least the little booklet could be taken openly into the exam room, which was handy for secretly writing helpful hints for formulae in tiny characters along the foldline.

ReplyDeleteJust this morning we bought some batteries in the local shop, handing over a £10 note in payment. The poor teenage girl at the till spent quite some time trying to work out the change. When P pointed out that the till was displaying how much she needed to give him, she was struggling with how that translated into the correct coin denominations to hand over.

I felt a little despair at that.

A girl at school got caught with tiny notes in her book at A Level. They annulled all her results, including O Level, and she left without qualifications.

DeleteComp operator was a good job back then, paid better than secretarial work. Funny that there are still people who know about them.

ReplyDeleteThere are many still younger than me who did the job.

DeleteI worked as a bookkeeper for an accounting firm and my fingers would fly over the 10-key calculator as I added up columns of numbers. We would write down the total and then zero it out to check our numbers. I was good at that!

ReplyDeleteI was a whizz with the early calculators when I needed.

DeleteI forgot about logarithms. I would think that the average citizen rarely uses long division.

ReplyDeleteI'm not so sure.

DeleteI guess I was just lucky at school. I copped logarithms and the slide rule. Fortunately my memory didn't waste space by finding a place to store such knowledge.

ReplyDeleteI am amused by the thought of leaving the machine counting upwards for days.

I never used a slide rule.

DeleteThe payroll manager where I worked in the late 1970s could check payslips using mental arithmetic, and he was more reliable than the computer, occasionally picking up errors. He had been just as skilled with LSD payslips, and used to reminisce about those times when anyone who handled money regularly, like shop assistants, could quickly work out change. Even then, the advent of the cheap Texas Instruments calculator meant that the school kids were no longer any good at mental arithmetic, and struggled with working out change at their Saturday morning jobs in the local newsagents - no smart tills then telling them the right change.

ReplyDeleteUs older folks were wary of the kids always believing the numbers on the calculator display, from having been caught out too often by a keying error somewhere along the way. I still use mental arithmetic regularly, I mentally totally up the checkout bill as I put goods in the trolley, and have often picked up checkout operators mis-scanning items when the total looks wrong.

My wife's grandfather used to add up as he went round the supermarket, and often correct the checkout.

DeleteAlthough I find mathematics and the almost magical quality of numbers fascinating, I was never very good with them and am glad that to this day I have not needed more than the absolute basics when, say, preparing an invoice to be sent to a client based on my hours/days and the hourly rate we charge for my services as a consultant in data protection.

ReplyDeleteI can tell when it's worth buying a monthly ticket (instead of tickets trip by trip) for local public transport and when it doesn't, and when a glass of wine at a restaurant is overpriced and similar things, and that's all I the maths I need in my daily life.

That seems pretter competent to me.

DeleteWhen the computers go down in supermarkets, they can't add up what your grocery bill is. It's crazy. Like you, I grew up being able to do it in my head, although I still struggle to know what use I have of logarithms and cosigns etc. My grandfather worked in a bank in the 1920s and had to add up pages and pages of figures in his head. No calculators then.

ReplyDeleteJust imagine the calculations needed for airships and the like.

ReplyDeleteThe paper long division I remember learning in maybe year 5 without quite understanding how it worked (more recently I sort of worked out how it worked but I have since forgotten how to do it) was how to find a square root.

ReplyDeleteThat's quite a still.

DeleteThis blogpost threatened to bring mathematical nightmares back into my non-mathematical brain. I thought I had finally expunged them in 1975 when I worked as a clerk in the catering stores at Butlins, Filey. All that bloody adding up and subtracting just about did my head in.

ReplyDeleteDid you really want to be a Redcoat?

DeleteI knew that that would not be possible as I was only there for half the summer season.

DeleteI remember long days in a classroom reciting 6x6 is 36. 6 x7 is 42. On and on we droned. Imagine my shock to learn that my grandson was having a horrible time in math. He was bringing home multiplication worksheets, studying fractions in the classroom. Then after a week they were doing division. It was nuts. In talking to the teacher, she explained that learning by rote is considered outdated. The expose children to all operations and expect that the kids will simply learn by repeated exposure. Over the summer my grandson and I spent an hour a day memorizing his multiplication tables and he was very unhappy with me. Next fall he went of to school and was amazed at how easy math became.

ReplyDeleteI hated math as a child, and I remember being sick with fear that I had forgotten how to do long division. All these years later, I love totalling things in my head to see how close I can come to the register total. I will readily admit my skills fall far short of yours, however.

Psychologists say having a range of different ways of understanding the same thing, and being able to transform one to another, is true understanding.

DeleteI too realized a few years ago that it had been forEVER since I’d even thought about doing long division, and I too tried it to see if I could still do it. Answer: Yes, very rustily!

ReplyDeleteSimilar to me, as you can seen .

DeleteI remember learning maths and time tables at school, it wasn't often I understood any of it either. But these days learning my times tables has paid off.

ReplyDeleteIt can be very useful.

DeleteHello Tasker,

ReplyDeleteIn our teaching days, now a mere memory, one of us taught mathematics and the other English. It has served us well over the years in covering all things both computational and creative provided that we work as a team, perhaps the greatest of lessons ever to be learned.

It is indeed very interesting how skill sets change and develop over the years. In Budapest when we first arrived some 25 years ago we marvelled at how there were few electronic cash registers and change was always counted out as it used to be. Now, more often than not, the change suggested by the cash machine is given in a lump sum....exactly as in England. However, in Budapest, there is still the skill of flat wrapping grocery items....long since disappeared in England but how long will it last here?

I wish we had flat wrap still. I dislike everything in plastic. But, supermarket profits win over everything.

DeleteBrilliant post, I remember back when I was a bus driver in the 90s the ticket machines didn't add up let alone work out cross boundary journeys, fare stages and the like. Most buses these days its all worked out and you pay contactless.

ReplyDeleteThank you. Those were the days.

DeleteI am not a fan of maths sadly but learnt my timetables happily. Something has been bothering me over the last couple of days. Remember you could get exercise books from Smiths and on the back was all sorts of information but it is that word (I will spell it wrongly of course) avordiopudus which keeps jumping into my mind and niggling. Does anyone know what it means from that obviously badly spelt word.

ReplyDeleteI've no idea. You can still get the books, but I have not seen any with the information.

DeleteAvoirdupois means having weight. It's the weight tables.

DeleteBloggers know some fascinating things.

Delete